Trial by ordeal: When fire and water determined guilt

- Published

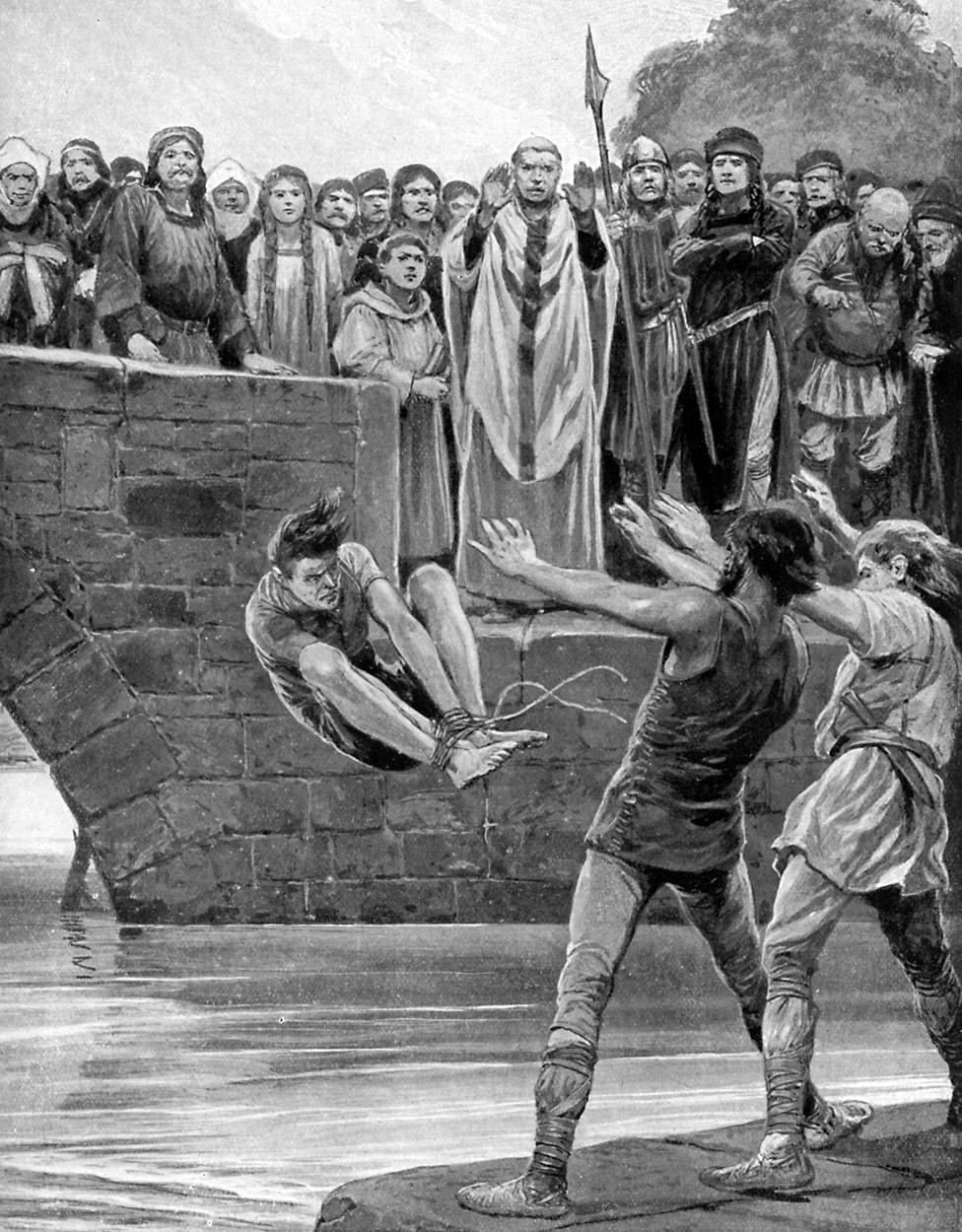

Trial by water, here illustrated for a 1920s history book, was one of the two main forms of ordeal

It is 800 years since England first started using juries to determine guilt. Before then, court could literally be an "ordeal" for those wanting to prove their innocence.

Ailward forced the lock on his neighbour's front door and entered - he was there to collect a debt he was owed. But, as Ailward searched the homestead, his neighbour Fulk returned and had him detained for theft.

Ailward protested his innocence. But he would have to undergo an ordeal to prove it.

He would be bound and cast into a pond. If he sank he would be innocent, if he floated - guilty.

He floated.

This was justice medieval England-style, and it was barbaric. Ailward's eyes were gouged out and his genitals mutilated as punishment.

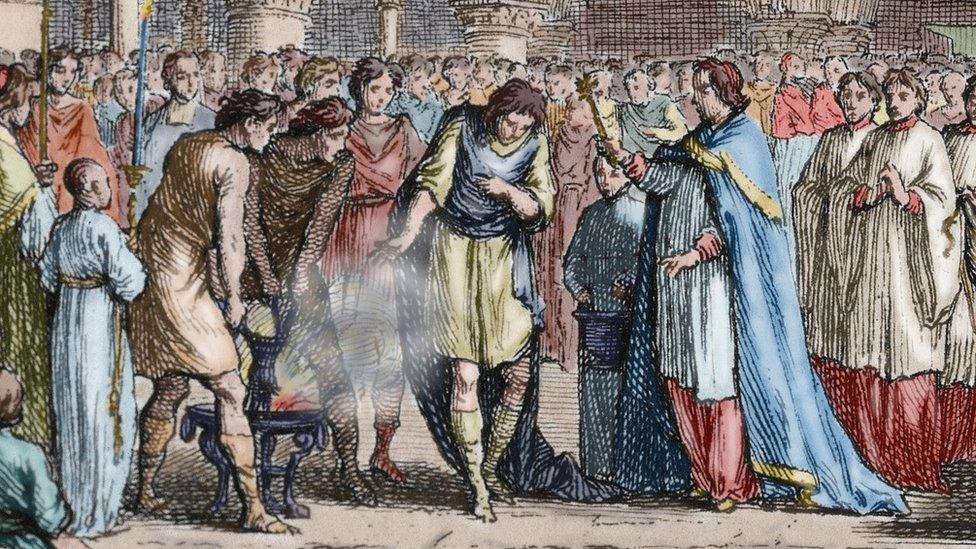

Trial by fire involved the accused carrying a red-hot iron

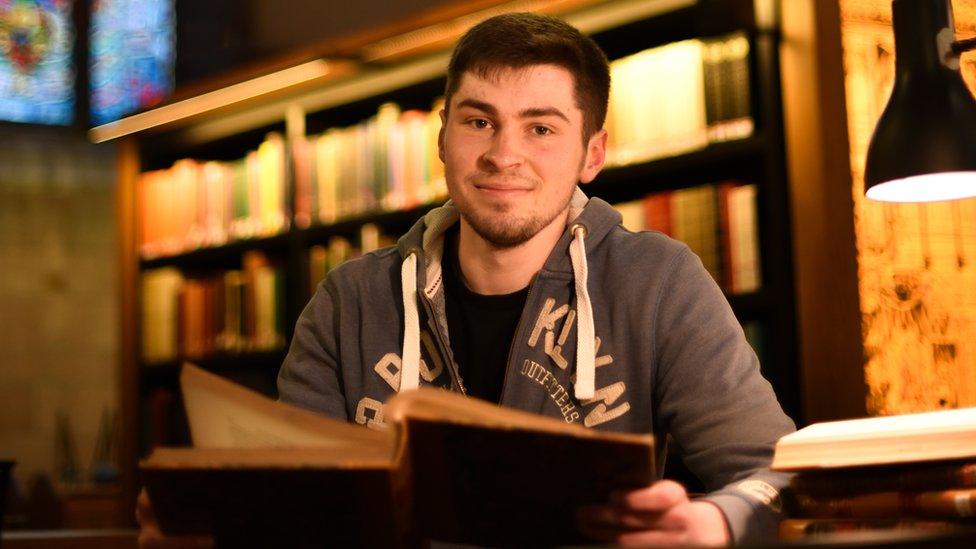

But, as daft as they might sound as a means of determining guilt, "ordeals" performed a useful social function according to Dr Will Eves, a research fellow at the University of St Andrews' School of History which will hold a debate about trials on 11 February, external.

"From a 21st Century point of view, it's very easy to look and say this was just the stupidity of earlier people but that would be wrong - there is much more nuance to it," he says.

There were two main forms of ordeal - fire and water - with God being seen as determining guilt through the result.

For fire, the accused had to carry a red-hot bar of iron and walk 9ft (3m). If the wound healed cleanly within three days, they were innocent. But if it festered, guilty. With water, the accused was plunged into a pool of cold water on a rope which had a knot tied in it, a "long hair's length" away from the defendant.

If they sank to the depth of knot, the water was deemed to be accepting them at God's behest. They were therefore innocent and dragged out before they drowned.

But if they floated the water was rejecting them, rendering them guilty.

The key to the ordeal was the interpretation of the result. The community would probably have had a good idea if someone had committed the crime or not so would interpret accordingly, says Dr Eves.

"In trial by hot iron, the issue wasn't if the iron had caused a wound but rather how it had healed," he says. "So that's a much more nuanced issue, much more open to interpretation.

"Whether the wound was festering was a judgement which could be influenced by the community's knowledge of the individual involved and their awareness of the broader circumstances of the case.

"Even in trial by water, the extent to which a person sank may have been open to interpretation, especially if they were thrashing around and the rope was being pulled in all directions."

Trial by combat, as depicted in Game of Thrones, was allowed by English law until 1819

Trial by combat

Another option was trial by combat or wager of battle - a fight between the accused and their accuser, which was introduced by the Normans in 1066 (and depicted in HBO series Game of Thrones).

God would grant the moral-victor the strength to vanquish the person who wronged them. But there is an obvious flaw - some people are simply better at fighting than others.

So a party could plump for a champion to fight on their behalf.

But again this would favour richer folk who could afford to pay for a better fighter.

"It was as obvious to them as it is to us that big guys would beat the little guy and they were concerned about it," says historian Prof John Hudson.

Trial by combat remained in English law until 1819, although its use had dwindled over the centuries.

In 2002, a man demanded trial by combat to resolve a motoring fine, external, but magistrates rejected his appeal and fined him.

Statistically, ordeals cleared more people than they condemned. They were not something to be taken lightly, a guilty person would have believed God would find them so.

So surely only a genuinely innocent person, who knows God knows their innocence, would go to an ordeal?

"It has been suggested ordeals were made easier to pass because of this attitude," says Dr Eves.

"The demeanour of the accused may have influenced the interpretation of the result of the ordeal."

It was the Church's decision to withdraw support for ordeals that ultimately doomed the practice.

In 1215 a papal council decree was issued - priests should no longer be involved.

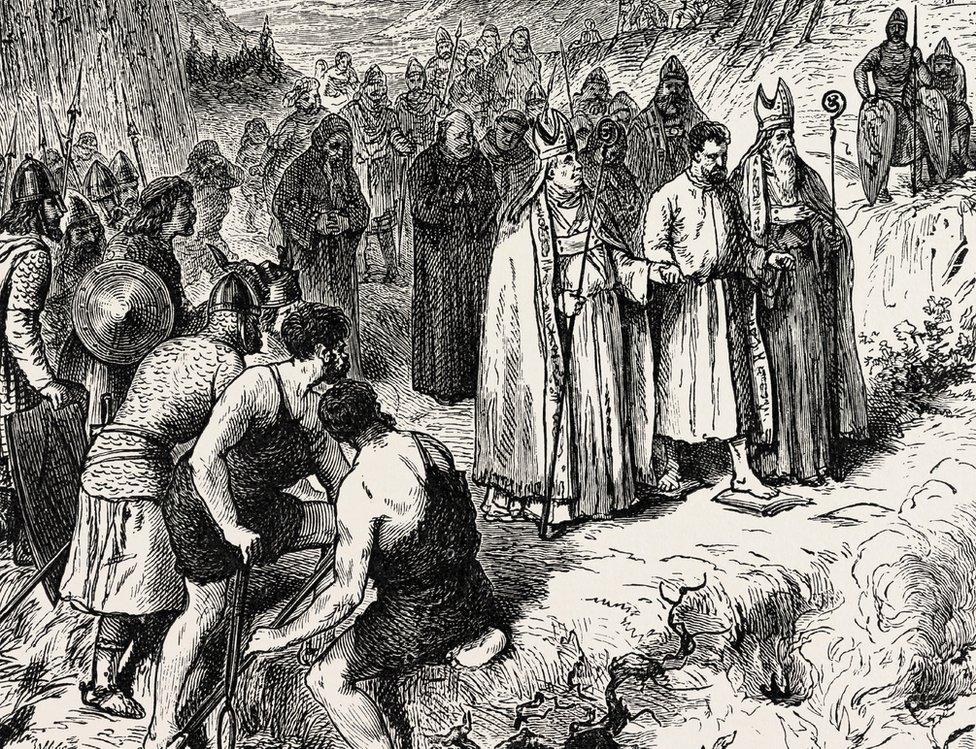

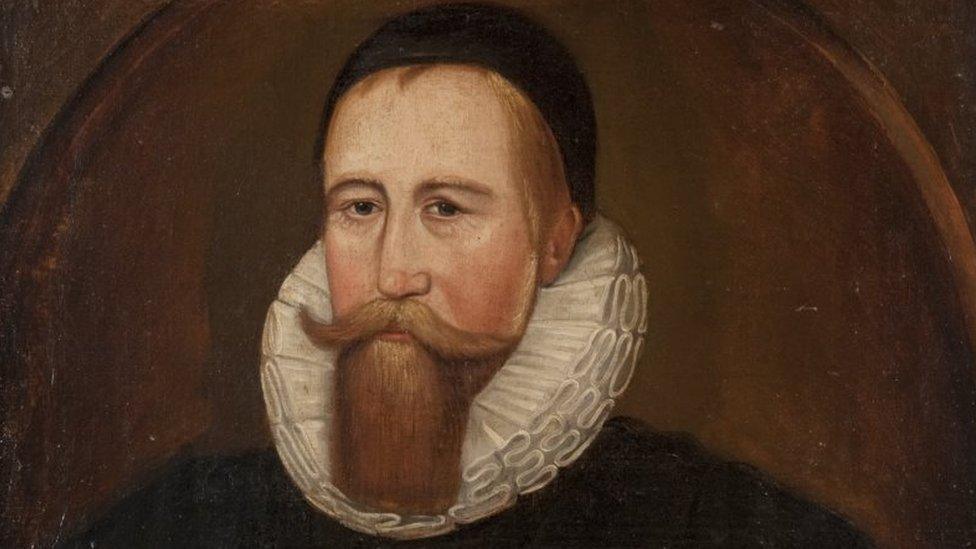

Priests were involved in verifying the results

The Church felt it was improper to ask God to intervene, it was akin to demanding a miracle.

As the priest was the one who oversaw the ordeal, blessed the water and iron and ensured the validity of the result, this effectively rendered ordeals impossible.

An increased understanding of science and rise in rational thought also saw the perceived infallibility of the ordeal diminish.

"There was a growing preference for human reason rather than the judgement of God," says Dr Eves.

So for four years there was no prescribed way of determining guilt.

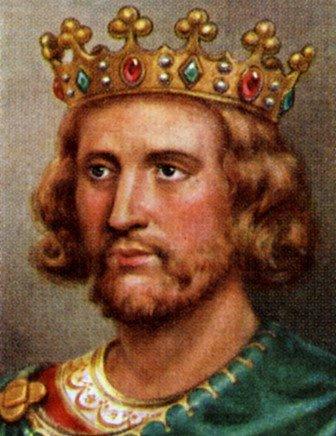

But on 26 January, 1219, King Henry III issued an edict - the trial by petty jury was born in England.

King Henry III, who introduced the jury trial

Juries had been around before, the grand jury gathered to ascertain whether someone was a suspect and should be put forward for the ordeal.

The petty jury simply moved that forward - a group of 12 people were now being asked to determine guilt.

Eight hundred years later, courts still turn to juries.

And defence barrister Harry Potter wouldn't have it any other way.

"This very important decision is made by an eclectic, arbitrary group of people based on their experience, conscience and understanding of the evidence presented to them, he said.

Mr Potter, who has been a barrister for more than 25 years, admits "no system is perfect" and said he had had "maybe three or four cases" where a client who was "undoubtedly not guilty" had been convicted, but that in many hundreds more the right verdict was reached.

"Most of the time they get it right," he adds.

- Published28 January 2019

- Published4 May 2016

- Published17 January 2019