Why more young people are using Crimestoppers

- Published

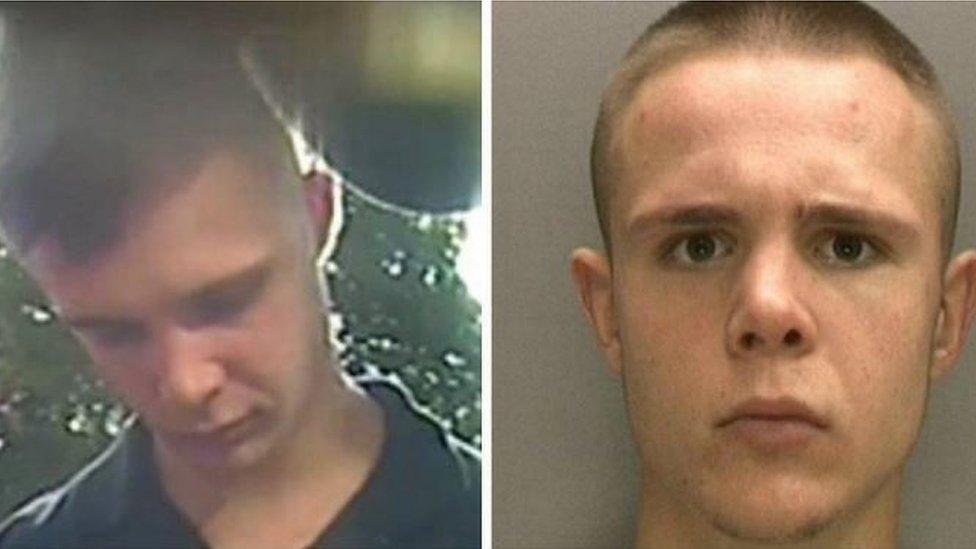

James Atherley was jailed for a minimum term of 26 years

Anonymous crime reporting service Crimestoppers is busier than ever. Almost half of those who contact it are under 35, and one in five is from black or minority ethnic groups. Why is that?

When 20-year-old Callum Lees died after being stabbed in the neck his killer went on the run.

Detectives soon suspected that the man responsible for the murder - in Solihull in August 2017 - was 21-year-old James Atherley.

They launched a manhunt and asked Crimestoppers for help.

The 30-year-old charity - which enables people to pass on crime information without revealing their identity - posted an image of Atherley on the "Most Wanted" page of its website.

Several weeks later, Crimestoppers was contacted by someone who thought they'd seen a man resembling him at a nightclub where he'd been in an argument.

The club was 200 miles away in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

"It was a key part of the jigsaw that led to the police arresting James Atherley," says Mark Hallas, Crimestoppers' chief executive.

Twelve months later, Atherley was convicted of Callum's murder and sentenced to life imprisonment, with a 26-year minimum term.

Callum Lees was found collapsed in a street

It's rare for Crimestoppers to trumpet its successes because it can't risk compromising the guarantee of anonymity that it provides to everyone who gets in contact.

Imagine a crime where a vital piece of information or the identify of a suspect is known by only a handful of people.

If it emerged that the details had been passed to Crimestoppers the perpetrator could find out who'd "grassed" on them.

Indeed, Crimestoppers goes to great lengths to ensure that no-one knows where the information it receives has come from.

No records are kept of the personal details, phone numbers or computer IP addresses of anyone who makes contact. It emphasises that it operates independently of, and in a different way from, the police.

Do the right thing

Mr Hallas says that partly explains why Crimestoppers is used by hundreds of thousands of young people and those from black and minority ethnic (BME) communities.

Mark Hallas said some people find it difficult to talk to the police

"Surveys we've carried out indicate that there's a hardcore of about 20% of people who find it very difficult to talk to the police directly under any circumstances - but many of those people want to do the right thing and we provide the avenue to let them do that," says Mr Hallas, a former brigadier whose 30-year military career included a spell in charge of Army intelligence.

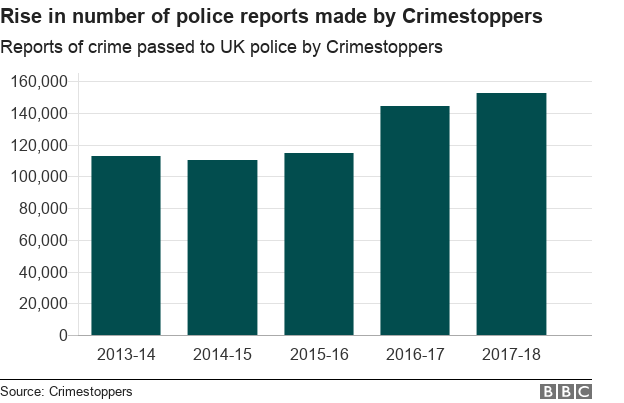

And the attraction of Crimestoppers appears to be growing.

Between July 2017 and June 2018, the organisation passed on 152,000 reports to police across the UK - up 6% on the previous year and 33% on 2015/16.

The increase is thought to be partly due to more Crimestoppers awareness campaigns and a simpler online reporting service.

But it also seems to reflect the overall rise in offences recorded by police in England and Wales - as well as problems people have reaching the police non-emergency number, 101.

"There is in some parts of the country an element of frustration with 101," says Mr Hallas. "They know if they call us they will be answered pretty quickly."

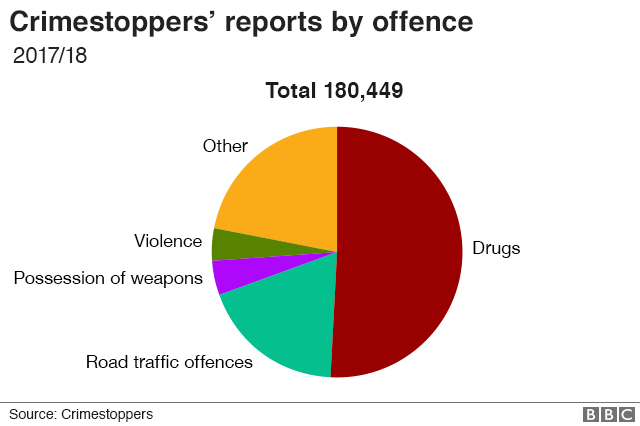

Some 60% of the reports Crimestoppers sends to police forces - 92,000 cases - are drugs-related.

Typically, they're sightings of dealers in cars or on street corners, details of cannabis factories, or intelligence about so-called county lines networks - the city-based gangs that supply drugs to rural areas and seaside towns.

Drug manufacturing

Last year, reports on drugs increased by 10%.

"People do see an awful lot of drug-dealing taking place, it's also drug manufacturing, and therefore it affects the fabric of their life and destroys their communities in many respects and so we get a disproportionately large amount of information in that area, and it's also linked to many other crimes as well," Mr Hallas says.

About two-thirds of the calls and online messages Crimestoppers receives at its contact centre in Godstone, Surrey, don't contain useful information and aren't forwarded to police.

Staff are aware of the pressures forces are under and don't want to waste their time.

But the information contained in 144,000 reports passed on in 2016-17 led to 3,300 people being arrested and charged; 16,700 dealt with in other ways, such as informal warnings; £7.4m worth of drugs seized and property valued at £814,000 recovered.

Nevertheless, the true impact of Crimestoppers is hard to measure because police don't always record what happens to the information they receive.

But with forces facing rising demand at a time of stretched resources, it's difficult to imagine how they'd cope without the service, which runs on a budget of £5m and includes a network of 400 volunteers.

Without Crimestoppers those seeking justice for the murder of Callum Lees might still be waiting.

- Published1 August 2018

- Published30 August 2017

- Published16 August 2017