The black history you might not learn at school

- Published

Black History Month is celebrated in the UK every October. As this year's celebration comes to a end, here are four lesser-known historical figures who helped shape multicultural Britain.

Una Marson (centre) worked alongside George Orwell (standing) and TS Eliot (seated), who are pictured looking over her shoulder

Una Marson - 'She was a real trailblazer'

Poet, dramatist, and broadcaster Una Marson made history by becoming the first black woman to be employed by the BBC.

Born in Jamaica, Marson moved to the UK in the early 1930s and took up her first position at the BBC as a programme assistant in March 1941.

"She was a real pioneer in giving voice to black women's experience, as well as generously creating a platform for other contemporary black voices," historian Robert Seatter says.

'Sparked resentment'

At the BBC, Marson worked alongside writers TS Eliot and George Orwell before establishing her own weekly feature within the Calling the West Indies radio programme, called Caribbean Voices.

She went on to become the first black producer at the BBC.

"This choice sparked resentment, but Marson was described as an extremely intelligent, loyal and lively person," Prof James Procter, at Newcastle University, wrote in 2015, external.

Robert Seatter says her ability to persevere despite prejudice highlights why "she was a real trailblazer" and should be remembered.

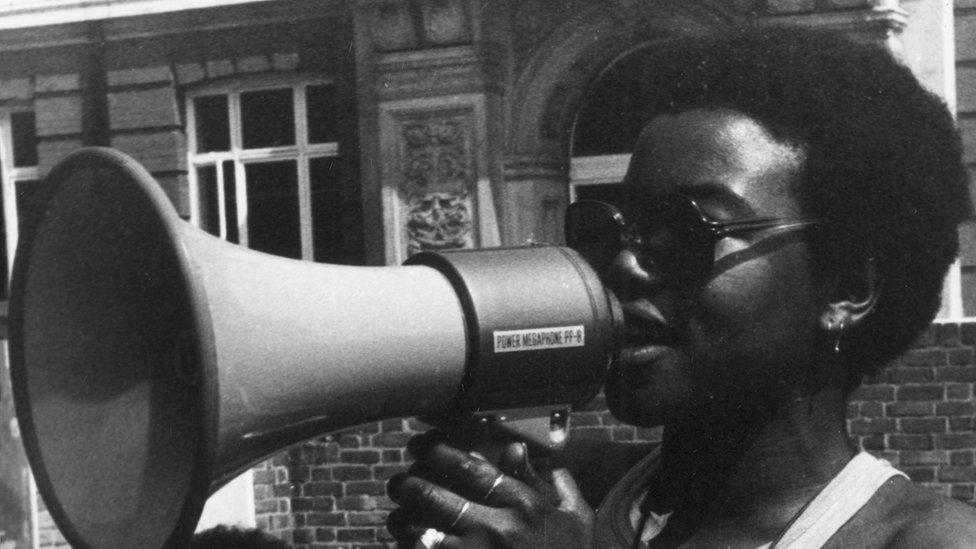

Olive Morris died at the age of 27 but "left behind an extraordinary legacy of activism"

Olive Morris - 'She left behind an extraordinary legacy'

Historian Angelina Osborne describes Olive Morris as a "radical activist and campaigner".

Born in Jamaica in 1952, and having moved to south London at the age of nine, she became heavily involved in community politics at a young age.

A picture of her taken in 1969 shows her face swollen, her clothes torn and dirty. On the back is written: "Taken at Kings College Hospital... after the police had beaten me up."

'Challenging oppression'

"Earlier that day," Angelina Osborne writes, external, "a Nigerian diplomat had parked his Mercedes on Atlantic Road in Brixton, leaving his wife and children in the car while he bought some records.

"Police officers, thinking the diplomat had stolen the car began to, according to witnesses, arrest him and beat him.

"Olive came forward and physically tried to stop the police from attacking the diplomat, causing the police to turn on her, arrest her and assault her, kicking her in the chest.

"This young girl, barely 5ft 2in, took on racist police officers, without thinking about her own safety, because she couldn't stand by and allow the injustice of an African man being arrested for driving a nice car.

"This was one early incident of Olive's commitment to challenging oppression."

Morris went on to co-found the Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent (OWAAD) and the Brixton Black Women's Group, which were among the first in the UK to address issues affecting women from ethnic minorities.

"Olive was committed to the struggle against racial, sexual and class oppression," Angelina Osborne says.

She died at the age of 27 but "left behind an extraordinary legacy of activism".

Frank Bailey joined the West Ham Fire Brigade in 1955

Frank Bailey - 'He never stopped fighting'

When Frank Bailey was told by a Fire Brigades Union (FBU) delegate that "black people were not employed by the fire service" because they were "not educated or strong enough", he decided to apply.

He successfully joined the West Ham Fire Brigade in 1955, becoming one of the first full-time black firefighters in the country.

However, Mr Bailey, who had moved to London from Guyana in 1953, left the service 10 years later.

His decision, according to Michael Nicholas, former FBU national secretary for black and ethnic minority members, was due to "inherent prejudice and racism" as white firefighters had been promoted ahead of him.

'Drive for equality'

"Frank was inspirational, as thoughts of black people at the time were very negative. Every day he had to consistently break down barriers," Mr Nicholas says.

"Everything he did was underpinned by his drive for equality."

After leaving the fire service, Mr Bailey went on to become the first black psychiatric social worker in London.

His daughter, Alexis, describes her late father as "inspirational".

"He went through so much and never stopped fighting for equal rights. He never gave up and that really inspired me," she says.

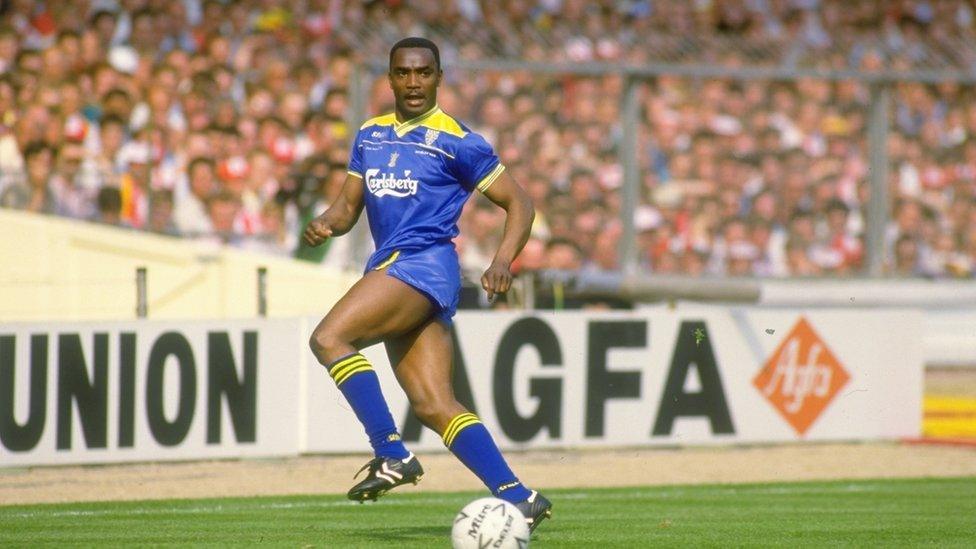

The year before he died, Laurie Cunningham helped Wimbledon beat Liverpool in the FA Cup Final

Laurie Cunningham - 'He made me believe'

Described as "one of the best players of the era", Laurie Cunningham was a leading personality on and off the football pitch during the 1970s and 1980s.

Born in London, the left winger began his professional career at Leyton Orient in 1974.

In 1977, he joined West Bromwich Albion and then became one of the first black players to represent England at any level, scoring on his debut for the under-21s, against Scotland.

Cunningham made his full international debut in 1979 and went on to earn six caps for England.

In the summer of 1979, at the age of 22, he became the first British player to transfer to Real Madrid, who paid West Bromwich Albion a fee of £950,000.

'Monkey chants'

"Laurie was one of the best players around at the time," former England striker Les Ferdinand says.

"In the past, black players were not getting opportunities to play for England - but Laurie broke down that barrier. He was so good that he couldn't be ignored."

Ferdinand says Cunningham, who died in a car crash in 1989, helped "pave the way" for black footballers.

"He made me believe I could be a footballer.

"He took a lot of stick that black players coming through now don't have to take.

"The black players took the brunt of it - such as bananas being thrown on the pitch and monkey chants."

Cunningham's career was a breakthrough in British football but Ferdinand adds: "We still need to break down barriers off the playing field, in terms of the boardroom, management, and coaching."