Crime increase: Has there been a move away from 'core' policing?

- Published

One of the UK's top police officers has called on forces to focus on burglary and violence, rather than devote resources to incidents such as misogyny where no crime has been committed.

Sara Thornton, the head of the National Police Chiefs Council, said there needed to be a "refocus on core policing" because there were "too many desirable and deserving issues" that officers simply could not respond to.

Who decides priorities?

Quite simply, every police leader. It's all a process of negotiation and agreement, which is rather complicated.

At the top of the tree, the Home Office has a list of national threats - such as counter-terrorism (its budget is ring-fenced) - but there's no priority-setting as such.

In fact, the Home Office's role has gone from clear target setting during the Tony Blair government years to handing a lot of this to locally elected police and crime commissioners (PCC).

The PCCs agree local priorities with the chief constables they appoint - they produce a weighty document called a police and crime plan - and then theoretically hold them to account for delivering them.

However - and this is the twist - the Home Office also controls a great deal of the policing budget. So, given that it has had cut budgets since 2010, chiefs wonder whether ministers should be a little clearer about what exactly they want forces to do less of.

Has 'core' policing decreased?

Police officers, in England and Wales, have been cut by about 21,000, or 15%, since 2010.

Historically speaking, using the most reliable measure, crime has been largely falling since the 1990s - but there are now increases in specific types of offences, such as violent crime.

Crime statistics are often misreported - and it doesn't help that there are questions over how good the police are themselves at recording what they hear about.

But other measures are useful.

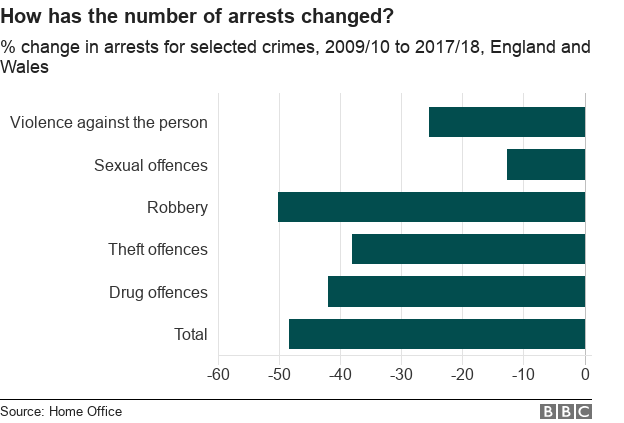

For instance, the number of arrests has been falling. and while this began in 2006, when crime was also falling, it has continued during a period of police recording crime rising.

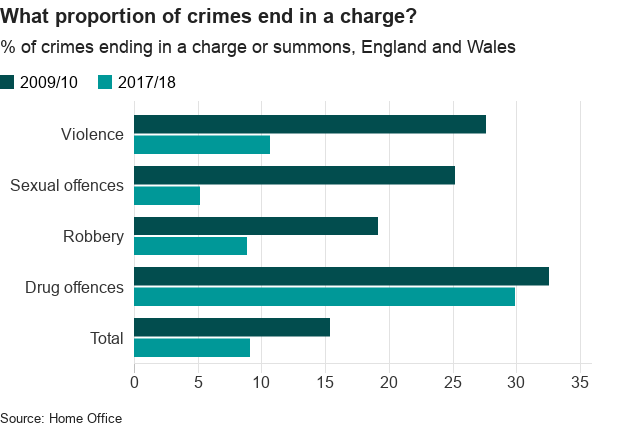

Figures gathered by the BBC show that the proportion of crimes that led to a charge, in four key areas - violence, sexual offences, robbery and drugs - are all down.

Now, on the face of it, this looks like evidence of the police struggling to get on top of things. But there are hints here and there of what looks like reprioritisation.

Penalty Notices for Disorder (PND) are a local policing tool. Neighbourhood officers issue small fines to people involved in low-level anti-social nuisance and offending in the hope of nipping a minor problem in the bud.

In 2010, police issued almost 141,000 PNDs. But last year, only 26,000 were issued - an 82% fall in their use.

Cannabis prosecutions have also fallen over the past decade - from 18,000 to 15,000 - despite the drug being reclassified as more harmful (from a Class C drug, to a Class B, in 2008).

Are we measuring police forces on their priorities?

Not really - but that's not to say they don't get measured in other ways. The unpronounceable HMICFRS - or Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services - is the national watchdog for policing. It looks at how individual forces are doing in protecting people, by scrutinising how police chiefs allocated their resources.

It has frequently raised questions about what should be part of the policing "front line" and has challenged forces to think of ways of to improve public trust.

What about misogyny?

This is where things get complicated. There has been an increasing focus in recent years on hate crimes that have long gone under-reported. Police chiefs began debating last summer whether they should add misogyny to the list of hate crimes, which currently covers racism and religious hate crime, among others.

Now, police officers regularly record incidents that later turn out not to be a crime.

Police recorded hate crimes have increased in recent years

Two years ago, Nottinghamshire Police began recording misogyny to see if it would help them keep women safe. This is part of a broader rethink suggesting police should always be focused on "reducing harm".

But the problem is, being a sexist pig, or worse, is not a crime, unless it results in threats or violence.

So, Sara Thornton's point was to question whether police should spend time recording incidents that are not crimes, when there are defined crimes such as burglary that need investigating.

Sue Fish, the former Chief Constable of Nottinghamshire, says she is disappointed at how the misogyny issue is being debated.

She told the BBC that in most of the misogyny incidents her force had investigated after the initiative had been launched, officers had found a crime had been committed.

Minister of State for Security Ben Wallace told the BBC: "What is really key is it's about harm. What harm is it causing you, your family and your community? And different crimes cause different harm in different parts of the country. And Sara Thornton is absolutely right that the priorities should be set by the police leaders and the locally elected police and crime commissioners."

Can police ignore crimes?

This is a grey area. Police regularly receive reports of what looks to the member of public like a crime, feels like a crime - but then an officer tells them no crime has occurred.

A classic example would be someone coming home and suspecting a would-be burglar has tried, and failed, to prise open a modern secure window.

And even when an investigation is possible, less than 8% of crimes result in a charge or court summons.

Almost half of investigations are dropped because no suspect can be identified.

But, interestingly, there are other cases dropped where the police have had a good sense of what happened.

One in 10 investigations is ended with the "support" of the victim after officers explain the evidential problems of landing a conviction. But a further 20% are dropped despite opposition from victims.

Could you sue your neighbourhood police for failing to find the burglar who broke into your shed because they're too busy looking into someone being sexist on social media? Not at all.

There is a long-standing legal principle that the police cannot be sued for negligence - although in a landmark ruling, the Supreme Court recently declared that forces could face claims for breaches of human rights if they botched investigations into the most serious of crimes.

That was a sign of the law giving chief constables a very clear sign of where their priorities should lie: the crimes that cause the most harm - and then everything else.