Remembrance Day: Pride and awe at the People's Procession

- Published

Emma Silk's grandfather, pictured in the photo she holds, lied about his age to join the war in 1917. He was only 17

"I want to honour the memory of my grandfather - what he did for our freedom," says Emma Silk, grand-daughter of Harold Victor Silk, who lost his left arm in battle the day before Armistice Day.

Emma was one of 10,000 people given the chance to take part in the People's Procession - a parade through London's streets on the 11th of the 11th, usually the reserve of the military.

Exactly 100 years to the day, WWI ended and cheering crowds gathered in Parliament Square and Trafalgar Square where they clambered on to the backs of the stone lions and lit a bonfire at the foot of Nelson's Column.

Today, the mood of jubilation has been replaced with a quiet pride and an awe at what our ancestors sacrificed for our freedom.

The grandfathers, great-grandfathers, and great uncles killed in bloody and bitter battles - their names remembered but often the circumstances of death still unknown.

The mother whose son - barely a man - never returned from the front; the young woman whose sweetheart went missing in action; the baby who was never to know his father.

Each one of the 10,000 people walking the length of the Mall towards the Cenotaph has a story to share - a name to remember, a photo in a pocket and often a medal pinned to their winter coat.

Many speak of the differences between then and now - the stiff upper lip of the last century, the generations who stayed silent about the impact war had on them and the buttoned-up manner of handling grief.

They tell their families' stories, blinking back tears in the low November sun. Even as years pass and the generation gap widens, the emotional connection does not appear to lessen.

'They died on the same day'

Roger Miles, 69, a retired interior designer from West Sussex, tells the extraordinary story that he only unearthed - almost by chance - four years ago.

His grandfather, Archie Miles, was wounded in the Battle of Cambrai, probably as the Germans launched a counter-attack.

His wife, Amelia, was told to get to France to be by her dying husband's side, which she did.

But as he lay dying, back home in Worthing their three-month-old baby son Tommy was also dying from whooping cough and pneumonia.

The two died on the same day.

Roger, a man of faith, said: "I like to think, maybe, Archie carried Tommy up with him."

Asked if he's marching for them, he replies: "I'm really here to honour the courage of my grandmother.

"She was obviously traumatised and remained a widow for the rest of her life."

'A gallant act'

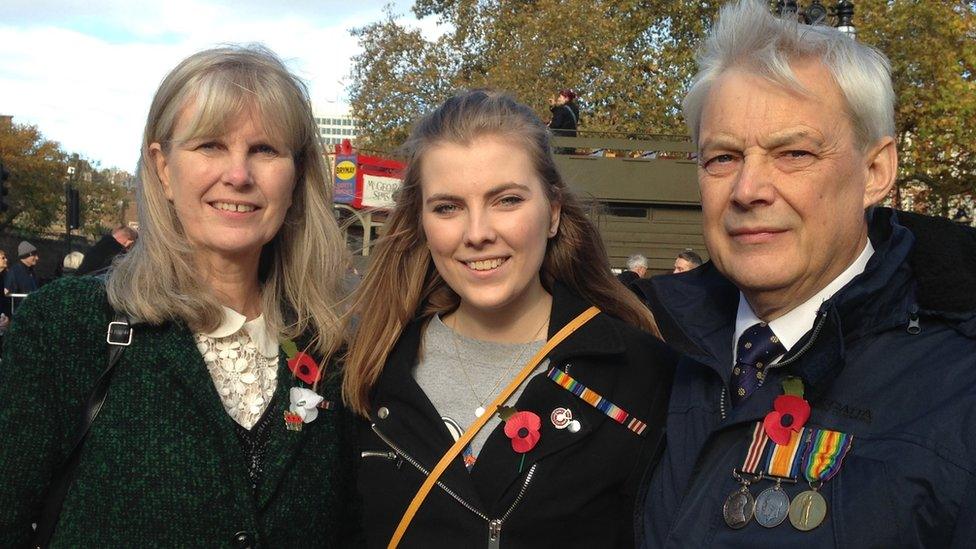

Jeremy Cripps, who attended with his wife Carol and daughter Jessica, wore his grandfather's medals

Robert Malin was working at St Pancras Hotel when war was declared.

At 27, he was sent to the front and given the job of bearer to send in stretchers and carry away the wounded.

But he went beyond the call of duty, says his grandson, Jeremy Cripps, 64, a children's charity boss from South Shields.

In the Battle of Amiens, in France, in the last 100 days of war, Robert Malin went out under fire many times to bring back the wounded.

Among them was Raymond Trustram, an officer, who made it out but died later from his injuries.

Robert Malin, left, went out with a stretcher under fire to save the wounded, including Officer Raymond Trustram, pictured here as a schoolboy

In an extraordinary letter of thanks, the officer's father wrote to Robert Malin to commend his "gallant act" and invite him to visit them.

"I thank you very much for what you did and feel sure you did everything possible," he wrote.

Robert Malin was later decorated for bravery. "Just pinning on the medals makes me feel emotional," says his grandson, Jeremy.

The heartbreaking letter

Jane Harman tells John Parr's story to children in school assemblies

Like so many on the parade, Jane Harman only knows the story of John Parr - the very first British soldier to die in WWI - after significant digging.

She pulls out her folder of archived documents - copies of the 1901 Census, birth certificates, letters - to tell a story to leave you dumbstruck.

John Parr is no relation but he was briefly a pupil at the primary school where she worked.

A North Finchley boy, he was 17 when he died two days before the start of the Battle of Mons.

It was 21 August 1914 but it was to be another eight months before his mother found out he was dead.

In a heartbreaking letter to the War Office, sent in October 1914, she wrote that she had heard from one of his "chums" that he had been shot down in Mons.

"I'm very anxious as it is now 10 weeks. If anything has happened to him by this time, someone would have wrote [sic] to me."

"You just can't imagine that," says Jane, a teacher in north London who has been telling his story to children in school assemblies.

"It's important the stories aren't forgotten," she says.

"What I've found heartwarming is how respectful all the children are - even children as young as six."

- Published11 November 2018

- Published9 November 2018

- Published25 October 2018

- Published9 November 2018

- Published9 October 2018