The challenges facing England's new prosecution chief

- Published

Max Hill QC takes up his role as head of the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), the chief agency for conducting criminal prosecutions in England and Wales, at a hugely challenging time.

Among the problems he faces are a 25% budget cut which has led to the loss of a third of CPS staff. The service, sometimes referred to as "the nation's law firm", has also been hit by a series of cases that collapsed because of failures by the police and prosecutors to disclose critical evidence to the defence.

And the number of people charged with rape in England and Wales has fallen to its lowest level in a decade.

Mr Hill, formerly the independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, will need to boost the morale of his 6,000 staff as he gets his teeth into issues on which he and they will be judged.

Disclosure

Disclosure is the bedrock of our fair trial system. In every criminal trial, the prosecution must disclose any evidence gathered by the police investigation which either helps the defence case or weakens its own. If that fails, miscarriages of justice can occur, and for years there have been problems with disclosure.

Last December, the rape case against Liam Allan collapsed when text messages were disclosed very late - three days into the trial - which proved his alleged victim had pestered him for "casual sex".

It was the first of a series of collapsed trials which led to reviews by the police and CPS, a National Disclosure Improvement Plan (NDIP), and, in July, a stinging report from the Justice Committee.

This found that, after six reports in six years from experts including judges and lawyers highlighting the problem, Max Hill's predecessor as DPP Alison Saunders had failed to recognise the extent and seriousness of long-term disclosure failings.

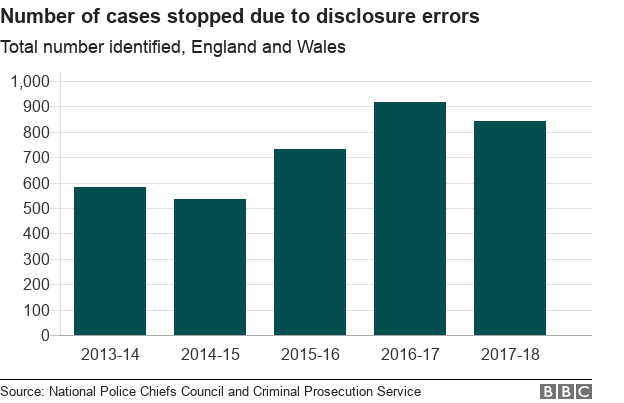

The committee found that she was not hands-on enough and her approach permeated the CPS. This wasn't helped by CPS data which may have underestimated the number of cases stopped with disclosure errors - by around 90%.

The report made clear that disclosure failings are systemic and not limited to rape and sexual assault cases. CPS data showed 841 cases in 2017-18 were stopped due to disclosure, but the committee said it knew that was less than the true figure.

If disclosure goes wrong, innocent people can go to prison. Alison Saunders told the Justice Committee that that had happened.

Responding to the Justice Committee report, she said: "Getting disclosure right is a fundamental part of a fair criminal justice system. I have been very clear that addressing the long-standing problems in managing disclosure across the criminal justice system is my top priority."

Max Hill is keen to be seen to be on top of the disclosure problems. He told BBC Radio 4's Today programme: 'We are committed at all levels in this organisation to making sure that these errors are driven down to an absolute minimum."

Alison Saunders' tenure as DPP was a controversial one

However, when asked if people were still in prison as a result of disclosure failures he said it was "impossible to know".

Identifying disclosure problems is the easy part, fixing them is hugely complex.

The NDIP has implemented a range of joint measures including:

Further training of police officers and prosecutors

Publication of a national standard on disclosure

A protocol on handling third-party material

An investigation of what technological tools might assist with the examination of the material

Stronger national and local leadership and oversight of the operation of the disclosure process

However, the law has hit a real problem in terms of the sheer weight of digital evidence - described as a "digital crater" by the Justice Committee - which now plays a part in many criminal cases.

A single mobile phone can generate upwards of 20,000 pages of evidence. The right skills and technology are needed to deal with the mass of evidence from electronic devices and that has huge resource implications.

It is likely that Max Hill will be making the case for greater resources here. He told the Today programme that in the lead-up to the next spending review "we will be marshalling our arguments to say how stretched we are".

Liam Allan's trial was halted after messages undermining the case were found

Current efforts to address disclosure failures will address present and future cases.

There are also demands, most recently from outgoing chairman of the Criminal Cases Review Commission Richard Foster, for a targeted review of past cases where errors may have resulted in miscarriages of justice.

"In my view the only proper course now is for police and prosecutors to themselves initiate a targeted review of existing convictions, starting perhaps with those from police forces where we know from inspectorate work there are ongoing problems with the quality of their criminal investigative work," Mr Foster said in October.

Max Hill says the CPS will look into any case "where an issue arises". However, a targeted review that looks at past cases would represent a challenge for the CPS.

Public confidence

The CPS must command public confidence. Max Hill believes that to build it people must understand the role of the CPS.

He is keen that the public realises that it doesn't investigate crime, or choose which cases it considers and is not there to secure a conviction in every case. Its job is to assess whether it is appropriate to present charges for the criminal courts to consider. They, and not the CPS, decide on guilt or innocence.

Public confidence will depend on CPS work being of the highest quality.

Max Hill has identified a number of challenges, including the fact that the CPS is demand-led. It obeys Parliament by prosecuting the crimes passed into law, and it responds to changing trends in crime by dealing with every case.

He believes that has resource implications. In recent years, the CPS has had to respond to big shifts in the mix of cases presented to it by the police. There has been a significant increase in complex cases including child sex abuse, economic crime and terrorism.

However, the new DPP accepts mistakes have been made, and says that the CPS is determined to learn from them.