Brexit: what is the withdrawal agreement?

- Published

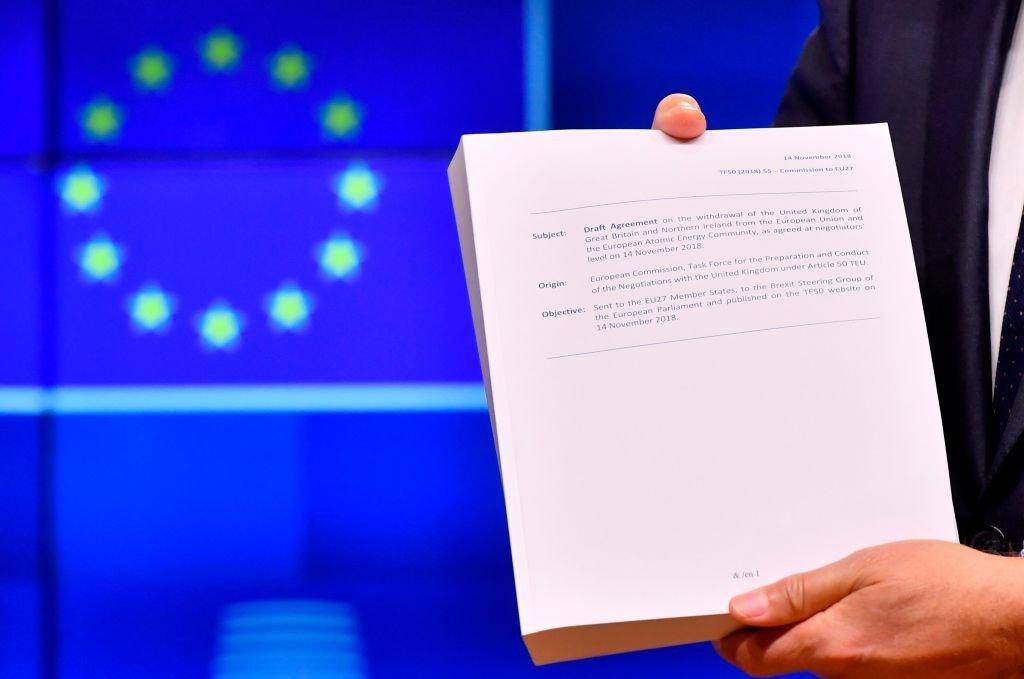

The draft Brexit withdrawal agreement stands at 599 pages long. It sets out how the UK leaves the European Union.

Chris Morris, from BBC Reality Check, has been going through it in detail and pulls out the key points from the agreement, external and what they mean.

Transition

The transition period (which the UK government calls "implementation period") is due to last for 21 months.

The UK will need to abide by all EU rules, but will lose membership of its institutions.

The draft withdrawal agreement says the transition can be extended, but only for a period of one or two years.

Both the UK and EU must agree to any extension.

Chris Morris's analysis: The details of transition aren't new but they are no less awkward for that. At a time when the government wants to trumpet that it is taking back control (its slogan, not mine), it will be ceding control for 21 months and very possibly longer. There will be no UK presence in the European Parliament, at the top table of the European Commission or in the European Court of Justice.

The UK will have no formal say in making or amending EU rules and regulations, but it will have to follow them to the letter. The great advantage of transition, of course, is that it buys more time for businesses and governments to prepare for a new regime, and it smoothes the path out of the EU. Transition also gives the UK continued access to EU databases on crucial issues like security while a future relationship is negotiated.

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

Money

The draft agreement sets out the calculations for the financial settlement (or "divorce bill") that the UK will need to pay to the EU to settle all of its obligations.

While no figure appears in the document, it is expected to be at least £39bn and it will be paid over a number of years.

Part of that money will be the financial contribution that the UK has to make during the transition period. In 2018/19 the UK's contribution to the EU budget is forecast to be a net £10.8bn.

If the transition is extended, there will have to be additional UK payments to the EU budget, which will be agreed separately.

Chris Morris's analysis: It seems a long time now since the size of the "divorce bill" was the big issue that was never going to be resolved, but the government knew that without a financial settlement, progress on other issues would be impossible.

Money remains a cause of controversy, though, because many Brexit supporters hate the fact that large sums will be handed over without any cast-iron guarantee about the nature of the UK's future trade relationship with the EU. Any refusal to pay, on the other hand, would sour relations and could - in extremis - end up in court.

Citizens' rights

This is broadly unchanged from the initial draft of the withdrawal agreement which came out in March.

UK citizens in the EU, and EU citizens in the UK, will retain their residency and social security rights after Brexit.

Citizens who take up residency in another EU country during the transition period (including the UK of course) will be allowed to stay in that country after the transition.

Anyone that stays in the same EU country for five years will be allowed to apply for permanent residence.

Chris Morris's analysis: The European Parliament has promised to make citizens' rights its top priority. But while politicians on all sides are telling citizens that they want them to stay, the Brexit process has caused an enormous amount of anxiety and uncertainty.

British citizens in other EU countries, for example, still don't know whether they will be able to work across borders after the transition period, because their right to reside only applies to the specific country where they live. Recognition of professional qualifications, and access to university education on the same terms they have now are also unresolved issues.

Northern Ireland/the backstop

If no long-term trade deal has been agreed by the end of 2020 that avoids a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and if there is no extension to the transition period, then a backstop consisting of "a single customs territory between the (European) Union and the United Kingdom" will be triggered.

Northern Ireland will be in a deeper customs relationship with the EU than the rest of the UK; it will also be more closely aligned with the rules and regulations of the EU single market.

As long as the backstop is in operation, the UK will be subject to "level playing field conditions", to ensure it cannot gain a competitive advantage while remaining in the same customs territory.

The UK cannot leave the backstop independently, it needs to be decided together with the EU.

Chris Morris's analysis: The single customs territory is basically another name for a temporary customs union and, if it were needed, it would ensure that completely frictionless trade could continue across the Irish border. But it would also prevent the UK implementing any trade deals with other countries around the world that involve removing tariffs on goods.

That upsets supporters of Brexit, especially as there is no guaranteed route out of this backstop unless the EU gives its consent. The Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland was the toughest part of the draft agreement to negotiate and, now it has been published, it has triggered a series of government resignations.

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

Fishing

The agreement says that a separate agreement will need to be reached on access to EU fishing in UK waters.

The document says: "The Union and the United Kingdom shall use their best endeavours to conclude and ratify 'an agreement' on access to waters and fishing opportunities."

Chris Morris's analysis: Fishing is always a hot button issue, even though in most countries the fishing sector forms a tiny part of the economy. Fishing has been left out of plans for a single customs territory because several countries objected to the idea that UK fish produce would be allowed unimpeded access to EU markets, without any corresponding guarantee that EU boats would be granted access to UK fishing waters.

It's an example of how negotiations on a temporary customs union were bound to throw up a host of complications - and a reminder of how tough negotiations on a future trade agreement are likely to be.

Laws and disputes

The UK will remain under European Court of Justice (ECJ) jurisdiction during the transition.

A joint UK-EU committee will be set up to try to resolve any disputes on the interpretation of the withdrawal agreement.

If the backstop is triggered and the UK forms a single customs territory with the EU, the ECJ will not be able to resolve disputes between the UK and EU directly.

Instead, the whole dispute resolution procedure will be backed up by an arbitration panel. However, if any dispute rests on the interpretation of EU law, the arbitration panel refers the case to the ECJ for a binding decision.

Chris Morris's analysis: Most of this draft agreement deals with matters of EU law, so the European Court of Justice casts a long shadow. The arbitration system for resolving disputes creates a semblance of independence and ECJ rulings will no longer have direct effect in the UK once transition is over.

That is an important point of principle for the UK government, but the European Court will continue to have indirect influence over the UK for many years to come.

What else is in it?

Elsewhere in the agreement there are protocols on Gibraltar and the British military bases in Cyprus.

There's a provision that the UK will withdraw from the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), which relates to how nuclear material is handled.

EU-approved geographical indications, protecting approved names like "Welsh Lamb" or "Parma Ham" remain.

Alongside the withdrawal agreement, there's the outline of the political declaration, setting out what the future UK/EU relationship might look like. It's currently only seven pages long but it's being fleshed out in negotiations that are still continuing in the run-up to the EU's Brexit summit on 25 November.

- Published16 October 2019

- Published30 December 2020