How I set out to catch a romance scammer

- Published

Catfish victim Roy showing reporter Athar Ahmad conversations he had with someone pretending to be someone else.

It's a tough conversation to listen to.

The woman on the phone thinks she has a fiancé in the US. But the romantic emails she's been receiving are really coming from a small town in Nigeria.

Laura Lyons has to break the bad news.

She's a private investigator who specialises in tracking down online romance fraudsters, otherwise known as "catfish".

"When you have to go back to individuals and explain to them that this person doesn't exist, they're not real, that is really hard to do," she says.

The catfish are often based in Africa and work from pre-written romantic scripts in internet cafes.

Their stories are designed to tug at the heart strings and to empty bank accounts.

More than a quarter of new relationships now start through a dating website or app, so there's no shortage of potential victims.

Most victims are too embarrassed to go to the police, but there are still 10 catfish crimes a day reported in the UK. Those affected by such scams lose on average around £15,000.

The mark: A victim who is targeted by romance fraudsters

Laura Lyons specialises in tracking down online romance fraudsters.

Roy Twiggs shows me the stream of email conversations he had with someone who pretended to be a US woman called Donna.

Roy thought they were in love and were going to get married. Then she started asking for money to help with a building project in Malaysia.

"The money seemed to be for plausible things. When you're sending £3,000, £4,000, it sort of all adds up.

"After I'd worked everything out I'd actually paid her the best part of £100,000."

The 67-year-old from Doncaster should be enjoying a comfortable retirement. Instead he's paying off creditors each month using his pension.

"I'm broke. You're whitewashed, you're totally devastated, you're finished, you just don't want to be bothered anymore."

While we are filming we spot a worrying entry on Roy's calendar. He has written "$500" next to the name Sherry.

Roy's calendar with a $500 payment to "Sherry"

Sherry is Roy's new American girlfriend. He met her online.

When I check the messages Sherry has sent, it's clear she's using the same language and methods as the original catfish.

It's far from unusual, as catfish are ruthless with their victims. If you have been hooked once, you are more likely to be targeted again.

The bait: A fake profile used to hook someone online

I want to catch a catfish by setting up my own fake dating profile. Nearly two-thirds of reported victims are women, so I have become Kathryn Hunter - a wealthy divorcee looking for love.

It's not long before the catfish begin to bite.

Four men approach me online and they all claim to be US soldiers. It's an immediate red flag. The military profile is a commonly used cover story which gives catfish an excuse not to meet in person, as well as providing a seemingly legitimate reason to ask for money to be sent overseas.

One of the soldiers, who calls himself Paul Richard, comes on strong. On day two, he tells Kathryn he's in love. On day three, he wants to marry her.

He takes the conversation away from the dating site and bombards me with texts. There are messages late into the night and more waiting for me in the morning.

After a week, Paul Richard says he wants to speak on the phone. My producer takes on the role of Kathryn for the call. The number he rings from has a Nigerian dialling code.

After a brief silence, a man with a thick African accent comes on the line. He doesn't sound like the American soldier whose picture he is using. But Paul explains away his accent by saying he has a cold.

The easiest way to prove someone is a catfish is to find the real person whose pictures they are using. An online reverse image search can show where the pictures came from on the internet.

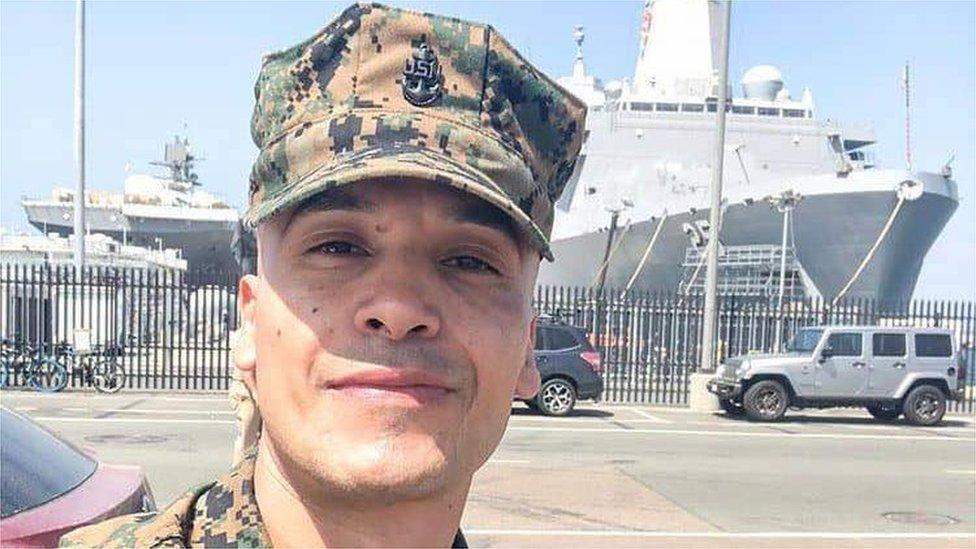

The first three photos Paul sends us don't work, because the meta data has been stripped from the picture. But we get a result on the fourth, a selfie Paul claims is him in his army uniform.

It leads us to the Instagram page of Juan Avalos, a real life marine whose page features the same pictures sent to us by Paul. He has uploaded a warning about catfish because so many fraudsters have been using his photos to scam people.

This is the image of "Paul Richard" we were sent by the catfish. His real name is Juan Avalos and his picture is being used by romance fraudsters. He's trying to raise awareness @shreddedmilitary

Juan told us: "These guys will say anything to anybody and lie. I run into so many messages, even if I show them it's not me they still don't believe it because they are so deeply in love."

For the next few weeks, my producer continues to speak to Paul Richard on the phone as I listen in.

Paul talks gushingly about their future life together and his plans to move to the UK to be with Kathryn once his army service finishes.

The conversations grow longer and more frequent, punctuated with kisses, flirtatious comments and a regular request for pictures.

There's just one thing standing in the way of our future happiness - Paul's son is sick and desperately needs medical attention. He asks for $800 (£620) to pay for young Rick's treatment.

Paul says we should pay the cash to his nanny in the US, a woman called Marcy Krovak.

It's a breakthrough because, unlike Paul Richard, Marcy Krovak is a real person.

Mule: Someone who transfers money or goods for the catfish

Catfish need real people to pick up cash for them as some form of identification has to be shown when collecting transactions. Some of these money mules are innocent victims tricked into forwarding on cash, others are in on the scam.

We don't know whether Marcy is in on it or not, so we head to Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania, where she lives.

We send her a small amount of cash to see if she will pick it up.

The next three days are spent sitting in a blacked out van outside Marcy's local Western Union.

We spot a number of women who look like her going inside but each time it's a false alarm..

Then, just as we think our sting has failed, we receive a notification telling us the cash has been picked up using Marcy's ID.

But it's been collected 400 miles away - in New York.

When we ask Marcy what's going on, she claims she's also a victim of our catfish: "I never was going to go to Western Union and pick that money up but now somebody's used my info and gone and picked it up. It was not me, I did not do it. Please find this person."

The reveal: Unmasking the catfish

It seems like we have hit another dead end, but then our catfish makes a mistake.

Paul Richard accidentally leaves a name tag - Dan Coolman - on one of his WhatsApp pictures.

We search through all the Dan Coolmans in Nigeria and we find one who runs a barbershop in Ibadan. He's using the same number that our catfish has been calling us from.

Dan Coolman is another false name, but we discover the phone is registered to Daniel Joseph Okechkwu.

We then find a Twitter account with that name and the same profile picture as the one used by Dan Coolman.

We have finally uncovered the real identity of our catfish.

Daniel Joseph Okechkwu - the man pretending to be Paul Richard.

We head for Ibadan, but by the time we get there he's gone. The doors to the barber shop are locked and locals say it's been closed for weeks.

There is a photo of our catfish posing with a customer on the side of the building, but no-one seems to know where Daniel Joseph Okechkwu has gone.

After three months of talking to our catfish, we decide to call him and tell him who we really are.

Reporter Athar Ahmad confronting the catfish on the phone

Surprisingly, he doesn't hang up straight away. He sticks to his story about being a US soldier and insists his name is Paul Richard. He denies scamming anybody and then ends the call.

It feels like a disappointing end to our search, but later that night he calls back.

This time, Daniel Joseph Okechkwu confesses. He claims it's the first romance scam he's ever pulled and that he has been forced to do it because of the closure of his barber shop.

He sounds sincere and he apologises for the way he has treated us.

Our catfish says he wants to stop being a romance fraudster. But he needs us to give him money, so that he can afford to stop tricking other people out of their cash.

It's a classic catfish twist. They never give up on the scam even when they have been rumbled.

You can watch BBC Panorama's Billion-Pound Romance Scam on Monday 19th November at 8:30pm on BBC One, or afterwards on BBCiPlayer.

- Published17 October 2018

- Published26 July 2018

- Published4 March 2017

- Published14 February 2017

- Published21 October 2016

- Published27 November 2015