Legal aid advice network 'decimated' by funding cuts

- Published

Legal professionals have warned cuts "threaten the quality of justice"

Cuts to legal aid have created "deserts" of provision across England and Wales, a BBC investigation found.

Analysis shows up to a million people live in areas with no legal aid provision for housing, with a further 15 million in areas with one provider.

Campaign group Liberty said access to justice had been "significantly undermined".

The Ministry of Justice said it took "urgent action" whenever it had concerns over provision.

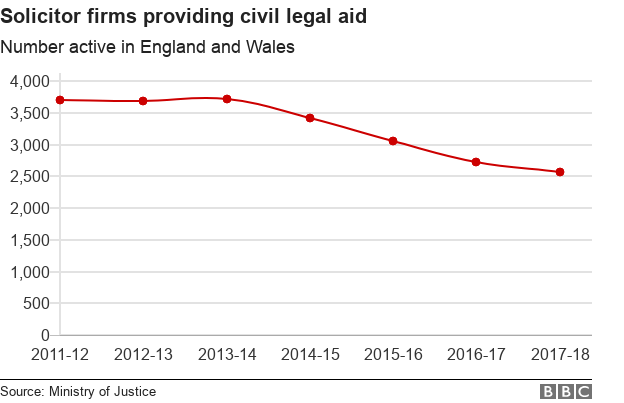

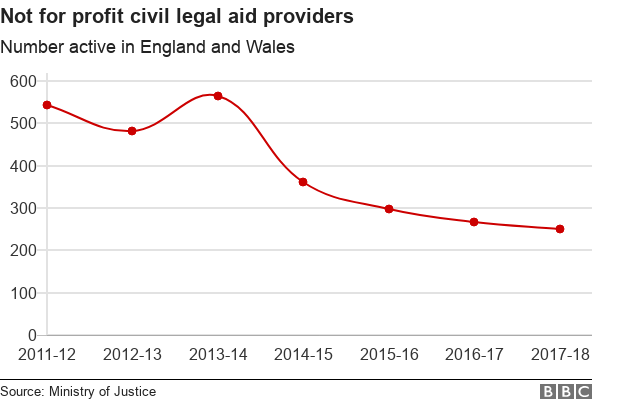

The BBC's Shared Data Unit has analysed Ministry of Justice and Legal Aid Agency data since 2011-12. It found:

Around a million fewer claims for legal aid are being processed each year.

More than 1,000 fewer legal aid providers were paid for civil legal aid work than in 2011-12.

Four legal aid providers for welfare cover Wales and the South West while 41 cover London and the South East.

Almost half of all community care legal aid providers are based in London.

Richard Miller, head of justice at the Law Society, said provision of legal advice across England and Wales was disappearing, creating "legal aid deserts".

"Even for those cases where legal aid is still supposed to be available, it can be very difficult for a client to find a lawyer willing to take on the case," he said.

This has prompted a more than five-fold rise in people representing themselves in court. Volunteers at the Personal Support Unit helped around 65,000 of them last year. Six years ago it was fewer than 10,000.

'Had I lost, I don't think I would be here'

Ian Howgate successfully fought two court cases alone, but said the experience was "terrifying"

Ian Howgate successfully fought two court cases alone after failing to find a legal aid solicitor.

The 54-year-old from Berkshire said his family was "living below the breadline" for more than a year after their housing benefit was stopped in 2015.

They were able to manage with the support of friends, and after winning his case Mr Howgate reclaimed £15,000 in lost income from his local authority.

Two months before that case was completed his son, recently diagnosed as autistic, was unfairly expelled from school and Mr Howgate had to bring a discrimination case on his behalf before a Special Educational Needs tribunal.

"People need to know this could be them tomorrow," he said. "We weren't able to even find a solicitor who, had we had the money, would be able to deal with the case."

Mr Howgate, who had been diagnosed with PTSD, said the courtroom experience had a dramatic effect on his mental health, and he had contemplated taking his own life as the case loomed.

"Preparing for it was intolerable," he said. "It is terrifying.

"As a lay person going into that courtroom it is like playing the lottery where your entire future is at stake.

"If you do not play your cards right, you are never going to forgive yourself."

The problem is recognised by court staff, who attempt to seek a fair outcome with litigants in person.

Malcolm Richardson, aged 70, retired as a family court magistrate in August after serving 37 years on the bench in the Bristol area.

He said legal advisors were increasingly having to guide litigants in person through the court process "out of necessity".

"It puts all the judiciary in a difficult position but also burdens the whole court system," he said.

"We are not there to sit as advocates, but as a human being who has committed themselves to judging their fellow man on sensitive issues, we all want to make the right decision.

"On many occasions in my courtroom, people have been reduced to tears, unable to cope and unable to put their view forward. Trying to help them do that is a harrowing experience for everyone."

'Invisible to the system'

The Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO) withdrew aid from areas of law including family, welfare, housing and debt.

It also lowered the means test and scrapped automatic eligibility for those in receipt of means-tested benefits.

Solicitors working on legal aid contracts say they have to turn people away "every single day", but there is no longer anywhere to send them.

Nicola Mackintosh QC, sole principal of Mackintosh Law, said: "We see people more desperate and in more extreme need than they were five years ago, and there is nowhere to send them. Those people are invisible to the system."

Nicola Mackintosh QC said the legal aid support network had been decimated

Her firm specialises in community care law, primarily for disabled people. With almost half of community care providers based in London, she travels across the country to reach clients.

She said: "Pre-LASPO, we had a network of advice centres, CABs, law centres and specialist high-street practices. It was not perfect, but it was pretty good. Now we have a complete decimation of the advice and representation network.

"Everybody recognises disabled people have rights but if you do not provide the advice and representation to them, those rights are theoretical in practice."

The people solicitors have to turn away will reappear in other public services, but only after their problems have spiralled out of control, says Steve Hynes, director of the Legal Action group.

He said the lack of legal aid supply was "shocking", while the MoJ said it "keeps availability under constant review".

"For many people across the country, getting help from a legal aid lawyer comes down to a postcode lottery which they are destined to lose," said Mr Hynes.

A false economy?

LASPO's objectives included making "significant savings" and delivering "better overall value for money".

But experts and campaigners say it has simply shifted the burden of cost onto the courts, NHS and social care - ultimately costing the state more.

And Labour's shadow secretary of state for justice, Richard Burgon MP, echoed the belief cuts to legal aid have been a "false economy".

"A lack of early legal advice can create unnecessary costs for the taxpayer as legal problems go to court when they could have been resolved earlier or spiral into costly social problems as people lose their homes or jobs," he said.

Shadow Secretary of State for Justice Richard Burgon MP

He added: "These figures highlight the grim reality of a justice system in crisis. These legal aid cuts have deliberately weakened people's ability to challenge injustices and enforce their rights."

Community advice 'shattered'

Gaps in provision of civil legal aid are often filled by law centres, which have formed in communities since the 1970s to meet need in more deprived areas.

But 15 centres have had to close since LASPO - 11 in the first 18 months, as funding was withdrawn.

Nimrod Ben-Cnaan, head of policy at the Law Centres Network, said the legal aid market was "failing" as cuts have "shattered local ecologies of advice".

"Legal aid deserts appear when there are not enough local providers of legal assistance, normally because of the Legal Aid Agency's preference of fewer, larger agencies, meaning that if those pull out of a local area there is little provision left."

Mr Ben-Cnaan said: "The lost goodwill, subject expertise and local knowledge would take time to be rebuilt - but it is vital for communities that they are rebuilt."

The MoJ last month agreed a £23m fee rise for criminal defence barristers last month, after the Bar took industrial action in April in protest over changes to the fee system.

An MoJ spokeswoman said there were "enough solicitors and barristers for criminal legal aid funded cases across England and Wales."

"Every person should have access to legal advice when they need it - that's why the Legal Aid Agency keeps availability under constant review and takes urgent action whenever it has concerns," she added.

The Government is undertaking a review of the impacts of LASPO - expected to be published by the end of 2018.

More about this story

The Shared Data Unit makes data journalism available to news organisations across the media industry, as part of a partnership between the BBC and the News Media Association. This piece of content was produced by local newspaper journalists working alongside BBC staff.

For more information on methodology, external, click here. For the full dataset on funding, click here, external. For the full dataset on provision, click here., external

- Published6 April 2013

- Published3 August 2015