The Skripals and the Salisbury poisoning: What happened next?

- Published

Throughout this week, we have been looking back at some of the BBC website's most-read stories of the year and asking: what happened after the news moved on?

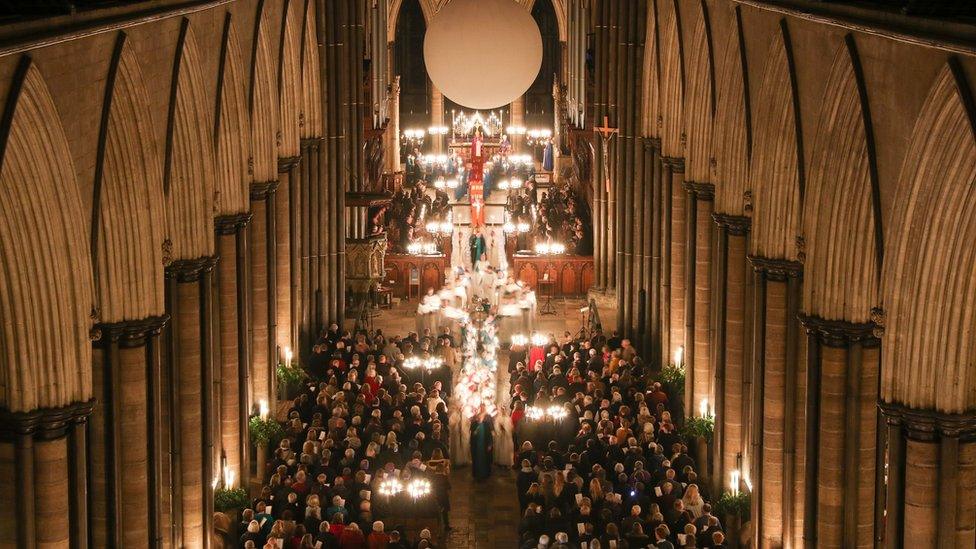

An advent procession inside Salisbury Cathedral: Tourism in the city has dipped since the poisoning

It was just a tiny bottle of liquid, but the use of Novichok, a substance from the past deployed as a devastating modern weapon, continues to have huge repercussions.

The three people who touched the nerve agent on the handle of Sergei Skripal's front door in Salisbury in March suffered appalling physical consequences, yet were saved by the expertise and care of staff at the city's hospital.

Each, in different ways, has lost their homes. Sergei Skripal will never return to his quiet street near the city centre. He is now a marked man, condemned by Russia as a traitor.

His daughter Yulia hopes to return to Russia but that must seem impossible for now. Both she and her father, a former Russian spy, are living in secret, protected by the UK.

Yulia and Sergei Skripal's whereabouts are unclear

Detective Sergeant Nick Bailey, the officer contaminated as he investigated, has had to move his family from their home, which may contain traces of Novichok.

But Charlie Rowley, who found the bottle of nerve agent and - thinking it was perfume - presented it to his partner Dawn Sturgess, lost someone he loved.

The most exposed of the Novichok victims, she rubbed the substance on her wrists, sealing her fate.

It was a devastating twist in a story that would have been hard to believe on the pages of a spy thriller. Rowley's health continues to be affected by his own poisoning.

Salisbury lost its peace in a year when the poisonings dominated life in the city, forcing residents to share their streets with the police, then the media, the military and finally the clean-up teams.

All of which meant the historic community lost business at a time when British high streets already face a fight to survive. Even now, the number of visitors is down 12% compared with last year.

The Zizzi restaurant reopened in November, eight months after the poisoning

Most of the places contaminated by the nerve agent are now cleaned up. Zizzi, the Italian restaurant where the Skripals had lunch, has reopened. The Mill pub, which they also visited, is being refurbished.

But Sergei Skripal's home in Christie Miller Road remains boarded and contaminated, as does Charlie Rowley's house in nearby Amesbury.

Britain won't set out the intelligence which informed its early declaration that Russia was almost certainly behind the attacks. Other nations with whom the intelligence was shared came onside with the UK quickly and firmly. But intelligence is not evidence. Usually it can't be published and it can't be deployed in court.

So when counter-terrorism police revealed they had identified two suspects from a painstaking search of CCTV, it was a critical moment. This was information which could be revealed.

Skripal poisoning: On the trail of Novichok suspects

Scotland Yard announced the cover names of the two Russian agents, Alexander Mishkin and Anatoliy Chepiga, in September, after holding back the information for weeks.

The hope was the men were unaware they had been identified, and would enter a country where they could be arrested and extradited. So far, that has not happened and Russia is certainly not handing them over.

Instead, in the modern way, they were ridiculed on social media for an interview in which they claimed their presence in Salisbury was down to a sudden interest in its cathedral. A fascination surprisingly put to one side once the Russian former soldiers experienced the harshness of a slushy British winter.

More than anything, Salisbury was a significant early moment in what is turning out to be a 21st Century sort of war - for the truth.

2018's big stories: What happened next?

The BBC has interviewed people who saw the aftermath of the poisonings with their own eyes. It is hard to believe that two Russians with apparent intelligence backgrounds just happened to be close by on the day an incredibly rare nerve agent developed in their country was used in Salisbury.

But the Russian state-friendly media, its social media supporters, human and automated, and the government itself, have constantly questioned Britain's narrative about the poisonings.

The men identified as Alexander Petrov (left) and Ruslan Boshirov (right) seen arriving at Gatwick

One example: when the Metropolitan Police published pictures of the two suspected assassins coming through Gatwick Airport, the Russian government suggested the pictures had been faked because timestamps suggested each man had been walking down the same corridor alone at exactly the same moment.

In fact there are several corridors, used by the border force to examine and photograph incoming passengers. They are identical and adjacent, making it entirely possible the men passed through simultaneously.

No matter. The waters of truth had been muddied.

That amounts to success in this new conflict. If the message can be undermined, then so can the messenger. If the messenger is your country's international rival, that can only help.

Of course, growing and secretive efforts to counter disinformation are an important part of what the British government does too.

But either way, the apparent attempt to kill a former Russian intelligence officer who spied against his country has at least left a feeling that the Russian state is not to be crossed.

Normality slowly returns to Salisbury. This Christmas the council funded a new outdoor ice rink to draw valuable visitors, a short walk from the area where in March space-suited investigators gathered evidence of a bizarre crime.

An event which is unlikely to be forgotten for generations.