Halt prison pepper spray plan, ministers urged

- Published

Ministers are being urged to reverse plans to issue prison officers with a synthetic pepper spray, known as Pava, following a trial.

From next year, canisters will be issued to staff in publicly run prisons for men, in a bid to reduce violence.

The Prison Reform Trust (PRT) says its own analysis of the six-month trial in four prisons showed the spray was often used "unsafely and inappropriately".

Ministers have said trials of the pepper spray were "successful".

The official report gives details of 50 cases where the chemical incapacitant was deployed.

The trials took place in four prisons: Hull, Preston, Risley and Wealstun in 2017 and 2018.

Officers were trained and issued with Pava, which was intended to be used as a last resort as a personal protection tool "to prevent harm to self or others".

In guidance, they were told to deploy it only when other techniques were not possible, had already failed or were considered unsafe or insufficient.

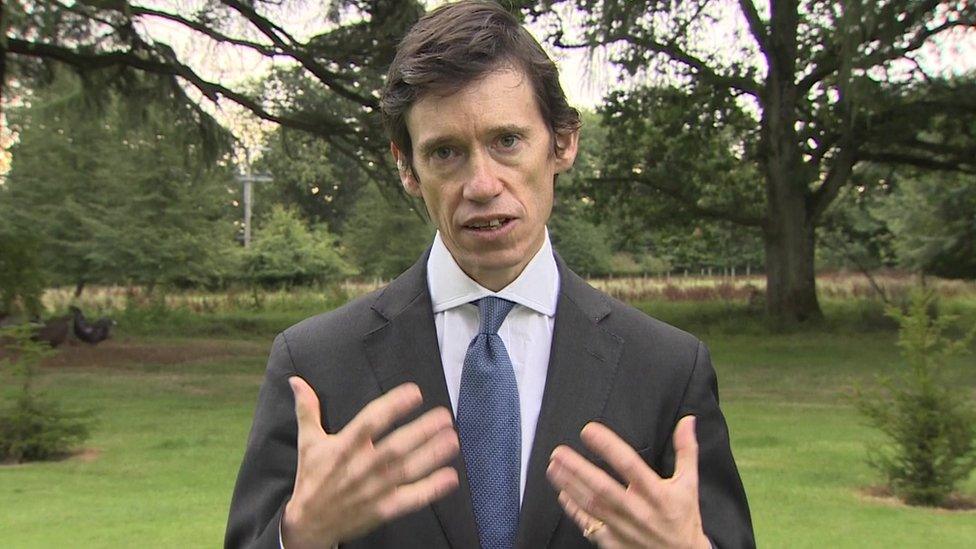

In a letter to the PRT in November, prisons minister Rory Stewart says the spray is intended for use "in exceptional circumstances where a member of staff is faced with serious violence or the perceived threat of serious violence".

However, the campaign group says its analysis, carried out by an experienced former prison governor, shows that in almost two-thirds of of these incidents, officers might have contravened the guidance.

"In fact, the use of Pava very rapidly became a routine part of how routine incidents were dealt with," says the PRT.

Incidents of inappropriate use in the official report include:

use against a prisoner who was harming himself

an inmate with mental health problems sprayed three times in 10 minutes, including at point blank range through a flap in his cell door

an officer spraying the wrong prisoner and a colleague attempting to intervene in a fight

use of the spray on a prisoner who had jumped on to the safety netting between the floors

Undermining trust

Overall, the analysis suggests that of the 50 incidents:

almost a quarter involved unsafe use, for example in confined spaces, at height, at point blank range or hitting the wrong prisoner or a prison officer

almost a quarter could have been resolved by other means - so Pava was not deployed as a last resort

a third involved use without appropriate justification, for example to enforce orders rather than to prevent serious harm

Hull prison was one of the four facilities used in the trial

The PRT warns that the use of Pava risks undermining trust between prisoners and prison officers and could lead to an escalation in violence as prisoners arm themselves against a perceived threat.

"At the very least, the minister should call a moratorium on the national roll-out until an adequate process of consultation has taken place," the group urges.

Rebecca Hilsenrath, chief executive of the Equality and Human Rights Commission, agreed there was no sound evidence to support the roll-out.

"We agree that it is of the highest importance that prison officers are able to protect themselves and others, but such protections must not be at the expense of the basic rights of prisoners," she said.

"Everyone has the right to live without fear of inhumane treatment."

A spokesman for the Prison Service said there was no evidence to suggest Pava was used unlawfully during the pilot and it would be wrong to imply that cases of misuse were ignored.

The spokesman said only officers who had completed specialist training were allowed to carry the spray, adding that the aim was not to reduce violence "but to reduce the harm that can occur during violence".

"We have taken on board lessons learned during the Pava pilot and are putting in place clear rules for its deployment, so it is only used when serious violence occurs or is threatened."

- Published9 October 2018

- Published17 August 2018