Why your name matters in the search for a job

- Published

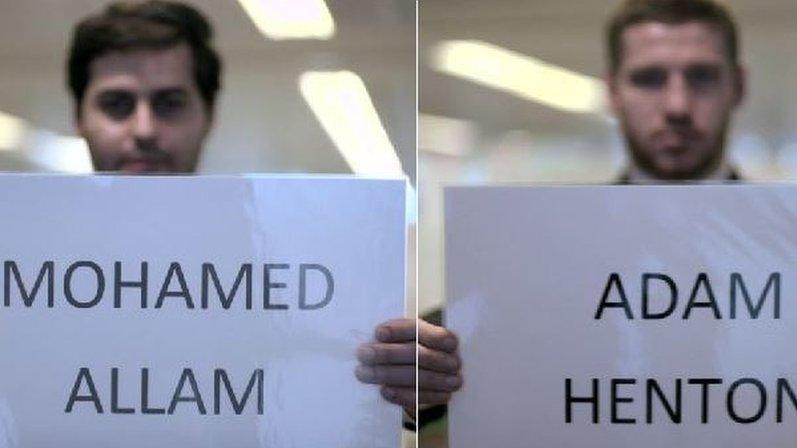

Rawan Mohamed says she had more success with job applications after she changed her name

"I grew up insecure about my name," says Rawan Mohamed, a British-Muslim of Sudanese heritage. "So I decided to change it to mask my identity."

The 22-year-old from Manchester says the success of her job applications has more than doubled since she started going by Rowan as a teenager.

"I think it confuses people," she says. "Interviewers usually think I'm mixed-race or Irish and don't expect to see a young black girl walk through the door."

Research carried out by academics based at Oxford University suggests her concerns may be right.

British citizens from ethnic minority backgrounds have to send, on average, 60% more job applications to get a positive response from employers compared to their white counterparts, according to researchers at Nuffield College's Centre for Social Investigation (CSI)., external

They sent around 3,200 fake job applications for both manual and non-manual jobs - including chefs, shop assistants, accountants and software engineers - in response to adverts on a popular recruitment site between November 2016 and December 2017.

All of the fictitious candidates were British citizens, or had moved to the UK by the age of six, and had identical CVs, covering letters and years of experience.

The only thing that they changed was the applicant's name, which they based on their ethnic background.

While 24% of white British applicants received a call back from UK employers, only 15% of ethnic minority applicants did.

Compared to White British applicants, people of:

Pakistani heritage had to make 70% more applications

Nigerian and South Asian heritage 80% more applications

Middle Eastern and north African heritage 90% more applications

'A burning injustice'

Dr Valentina Di Stasio, co-author and an assistant professor at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, says the "shocking" results show that the level of discrimination in the job market has not changed since the late 1960s.

"Because all of the minority applicants in our experiment were either British-born or had been British-educated from a young age, concerns about poor English language can't explain the large gaps in call-backs from employers," she says.

"It suggests that employers may simply read no further as soon as they see a Middle Eastern-sounding or African-sounding name."

Prof Anthony Heath, the director of the CSI and emeritus fellow of Nuffield College, said: "The absence of any real decline in discrimination against black British and people of Pakistani background is a disturbing finding, which calls into question the effectiveness of previous policies.

"Ethnic inequality remains a burning injustice and there needs to be a radical rethink about how to tackle it."

'An old boy's network'

Miriam Animashaun says she "very nearly" changed her Nigerian name after struggling to find work

Miriam Animashaun, 24, from London agrees.

She graduated from Southampton University in 2016 with a 2:1 degree in Economics and Philosophy but it took her more than a year to secure a job, despite having completed a placement at an international consulting firm in Sydney during her studies.

Most of the students on her course had been offered jobs before graduation.

"I was sending on average around 35 applications before I'd even get an interview," she says. "I very nearly changed my Nigerian surname."

She now works as a trainee insurance auditor and says the sector is still very much like "an old-boy's network".

"They look at our names and think about who would fit in," she explains.

"Most of the socialising in the industry revolves around drinking and this culture excludes people from Muslim backgrounds."

Dr Zubaida Haque, the deputy director of the race equality think tank Runnymede Trust, said the research was the "most conclusive evidence that overt racial discrimination still exists".

"Nowadays a lot of the conversation is about unconscious bias, but this shows that no matter your degree or education, you are still perceived and treated by the colour of your skin, religion and ethnicity, and not by what you can do," she told the BBC.

Last month the Resolution Foundation found that, overall, the 1.9m black, Asian and minority ethnic workers in the UK are paid about £3.2bn less than their white counterparts every year.

- Published6 February 2017

- Published7 December 2018

- Published26 October 2015