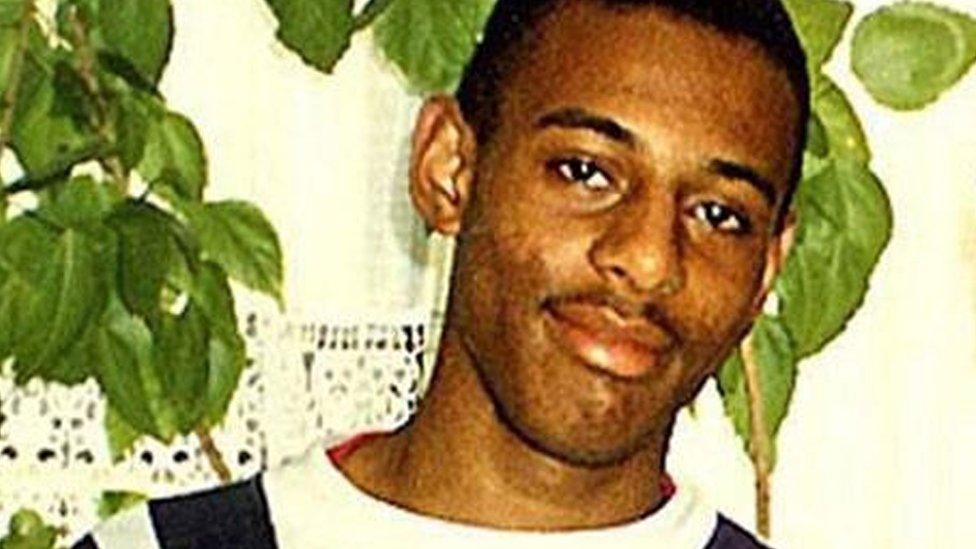

Stephen Lawrence: How has his murder changed policing?

- Published

The murder of Stephen Lawrence led to a wide range of changes to policing

Twenty years ago, an inquiry into the death of teenager Stephen Lawrence called for an overhaul of police procedures and attitudes towards race. But how much has changed?

One of the first acts of the Labour government in 1997 was to announce a public inquiry into the murder of Stephen Lawrence.

The black teenager had been stabbed to death in a racist attack in south-east London four years earlier. The case achieved national prominence amid claims of police ineptitude, racism and corruption.

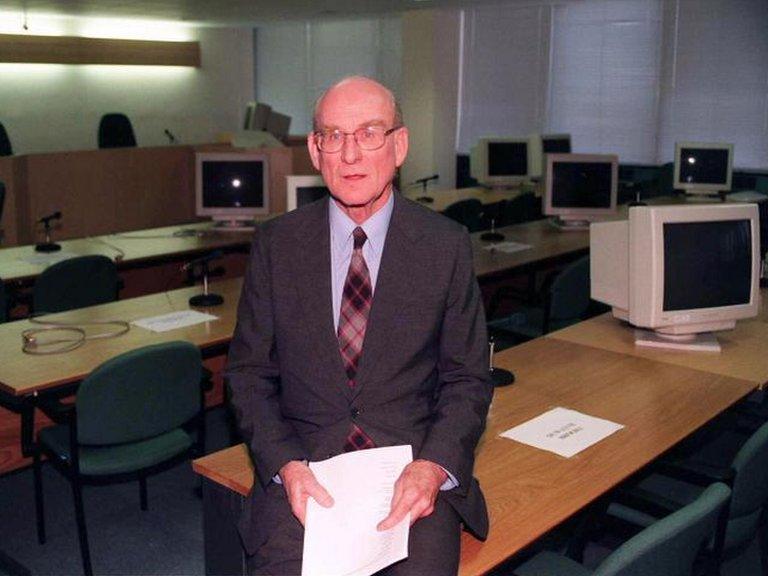

The inquiry - led by retired High Court judge Sir William Macpherson of Cluny - heard evidence from 88 witnesses and considered 100,000 pages of statements and documents.

When the inquiry report was published, external, in February 1999, it created shockwaves through policing.

'Institutional racism'

Its central conclusion was that the investigation into Mr Lawrence's killing had been "marred by a combination of professional incompetence, institutional racism and a failure of leadership".

The findings in the 350-page report, particularly the charge of "institutional racism", have had a profound effect on the culture, operations and practices of the Metropolitan Police Service, other forces across England and Wales and the wider criminal justice system.

Sir William's inquiry made 70 recommendations. By the time of the 10-year anniversary, the Home Office said 67 of them had been partly or fully implemented.

Sir William Macpherson chaired the inquiry

They included a number of practical proposals to improve murder investigations and the treatment of victims of crime, such as first-aid training and dedicated family liaison officers - fundamental changes that have made a lasting difference.

The inquiry also paved the way for a change in the law so that suspects acquitted of serious crimes could be prosecuted again where fresh and compelling evidence emerges. This legal reform - which was resisted by some lawyers and judges - enabled one of the men suspected of Stephen's murder, Gary Dobson, to be put on trial for a second time: in 2012, he was convicted, along with David Norris.

Restoring trust

Importantly, the inquiry also heralded an overhaul of the police disciplinary and complaints system, enhanced powers to inspect forces and measures to promote diversity and tackle racism in schools.

Indeed, Sir William said a key aim of his proposals was the "elimination of racist prejudice and disadvantage and the demonstration of fairness in all aspects of policing". He devised a series of performance indicators to hold police to account, among them measures to ensure racist crime was logged and dealt with effectively.

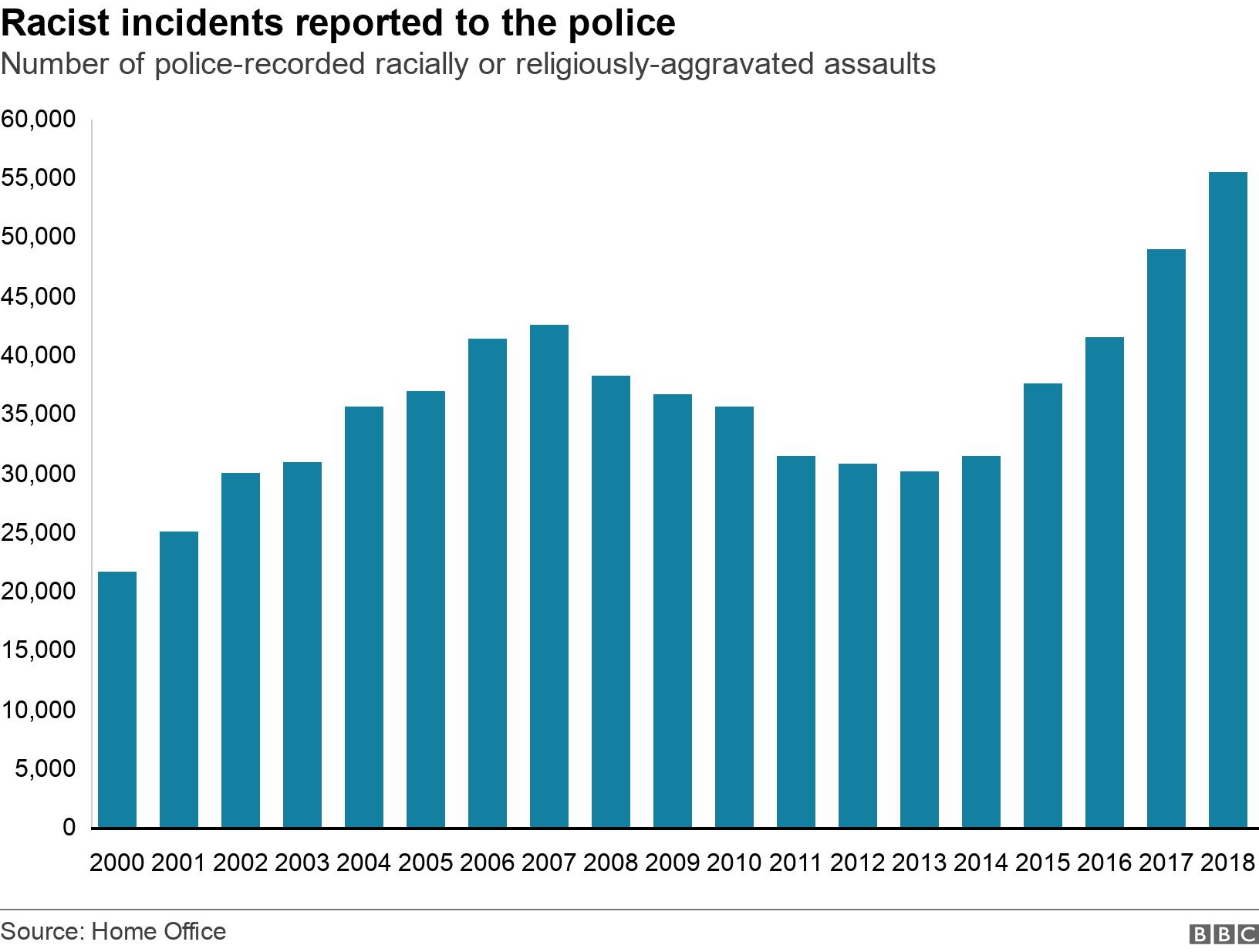

Since 2000, there has been consistent recording of "racially aggravated offences" in England and Wales, which shows a rise from 21,750 to 55,557 in 2018.

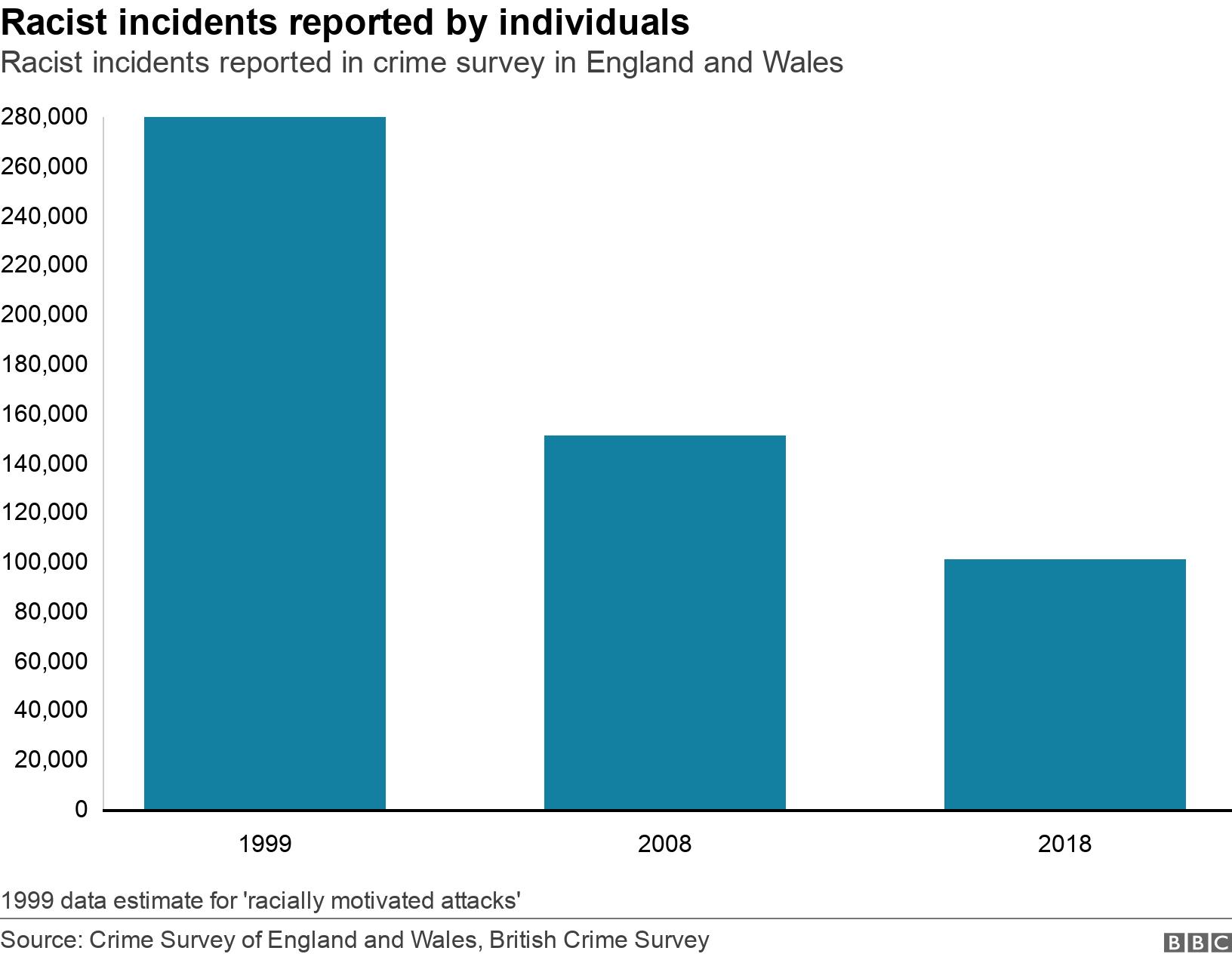

That's an increase in the number of incidents recorded by the police. But data from official surveys asking people about their experiences of crime suggests racist incidents have fallen - from 280,000 to 101,000 over roughly the same time period.

This indicates that there has been a decline in racially aggravated offences but, where they do occur, people are more willing to report and police are better at recording them.

The inquiry said government ministers should make it a "priority" to "increase trust and confidence in policing amongst minority ethnic communities".

Figures from the Crime Survey of England and Wales suggested there was a similar level of satisfaction with the police among white and black people in 2017-18, with 78% and 76% respectively saying they had confidence in their local police force.

But breaking this down further suggests that people from the black Caribbean community have lower confidence in the police (71%) and people of mixed-white-and-black Caribbean heritage have lower confidence still (67%).

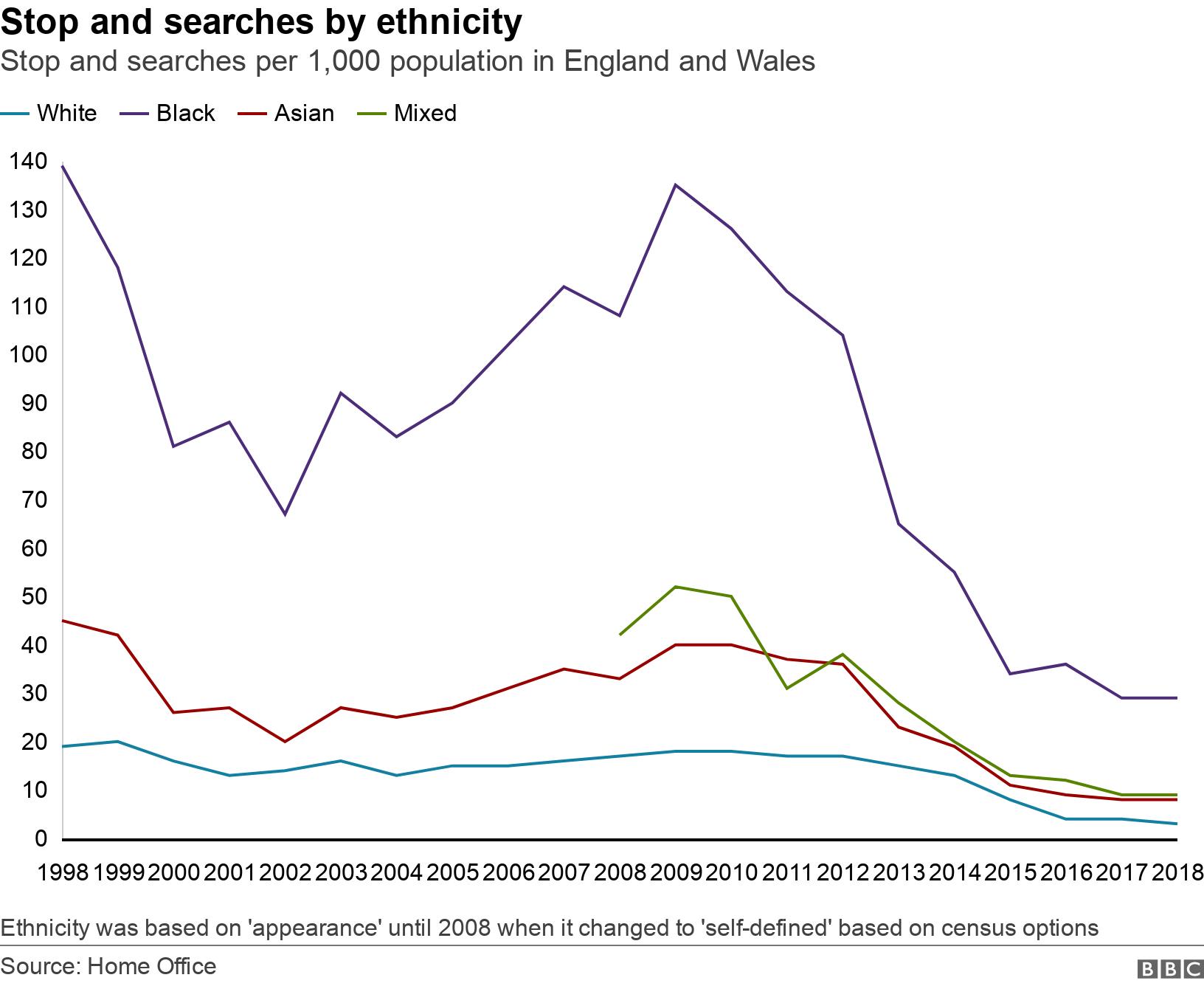

Sir William said the need to re-establish trust between minority ethnic communities and the police was "paramount". One obstacle he identified was the use by police of stop-and-search powers, saying that "the majority" of officers who testified accepted that discrimination played a part.

Statistics at the time showed that black people were five times more likely than white people to be stopped and searched for drugs, weapons or stolen goods. He recommended that police record the details of each stop and log the ethnic identity of those involved.

Although the overall number of stops has fallen - particularly after they were singled out as a source of tension that had contributed to the 2011 riots - they still disproportionately affect black people.

In his 2017 review of the treatment of black and minority ethnic groups (BAME) by police and the courts, David Lammy MP said this disparity led to a view among BAME communities that the justice system remained "stacked against them".

However, the Met, which carries out more stops than any other force, has robustly defended the tactic, saying that boys and young men, particularly of black Caribbean heritage, are more likely to be victims and perpetrators of street violence and knife crime than other ethnic groups.

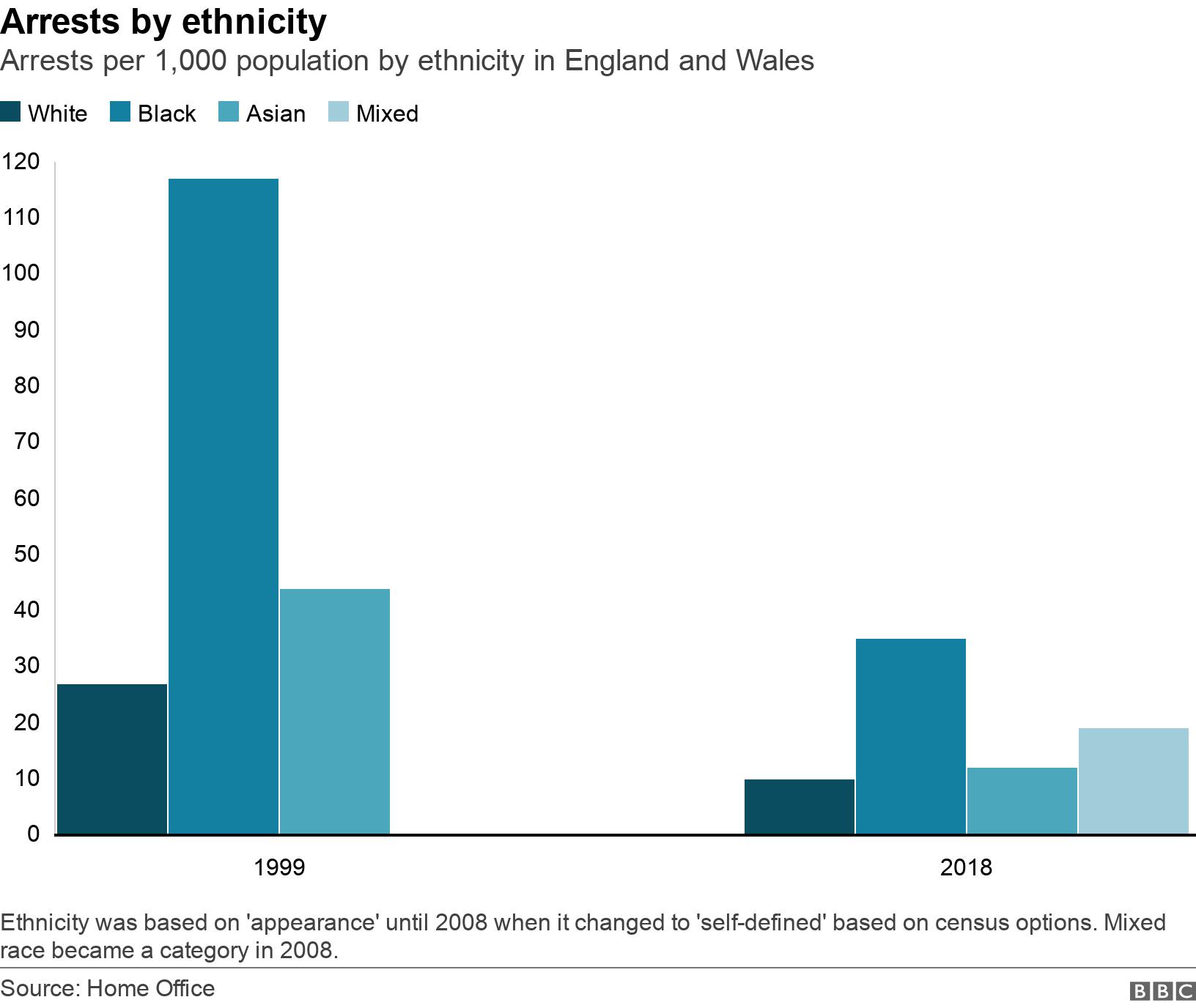

Figures on the ethnic background of people who are arrested also show that black people are disproportionately affected, though the gap is not as great as it was when the Macpherson report was published.

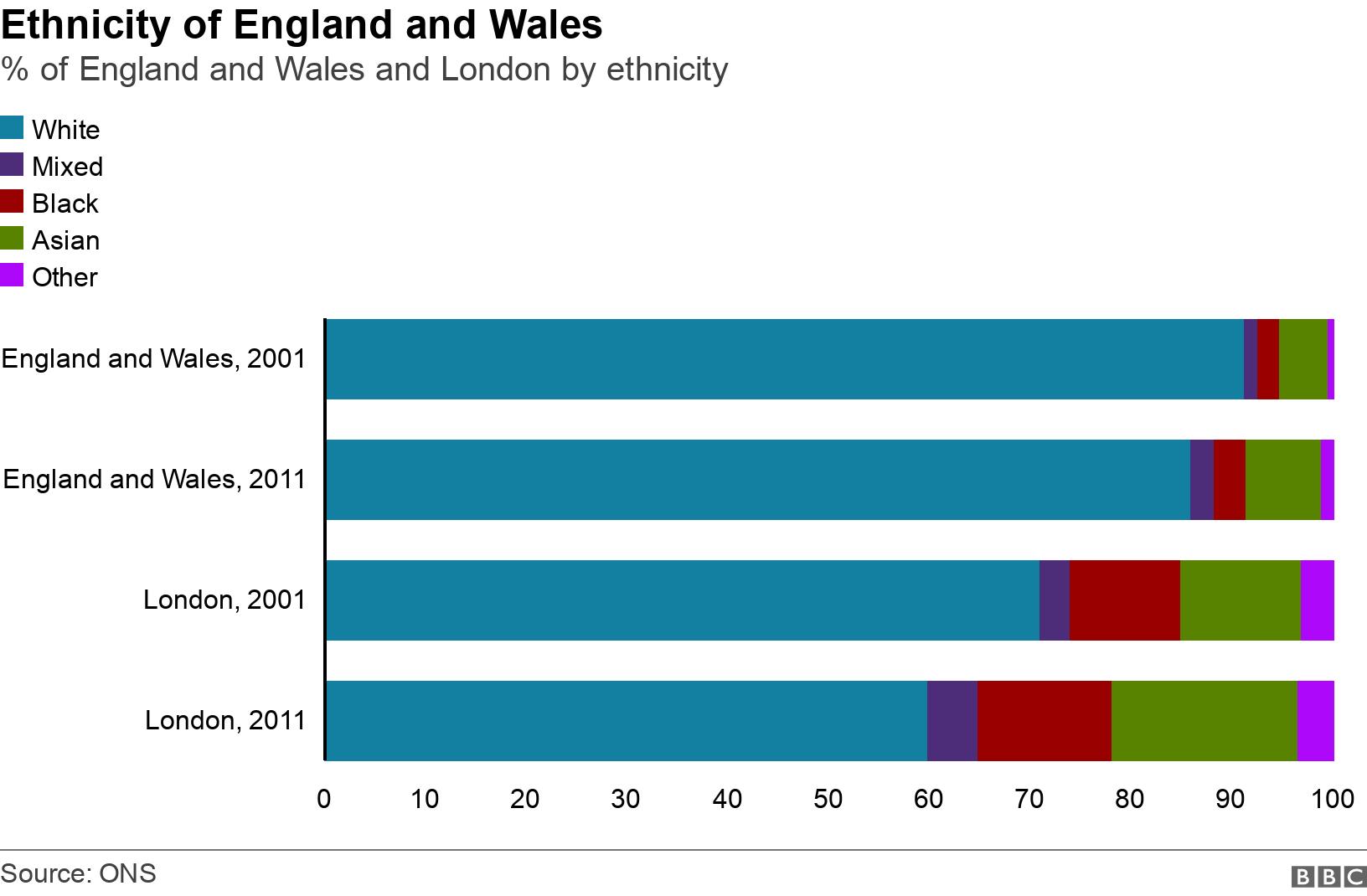

The figures take into account the changing ethnic mix of the population over the past 20 years. Britain has become a more diverse country, which has only served to strengthen the argument, put forward by Sir William, for the police service to better reflect the communities it served.

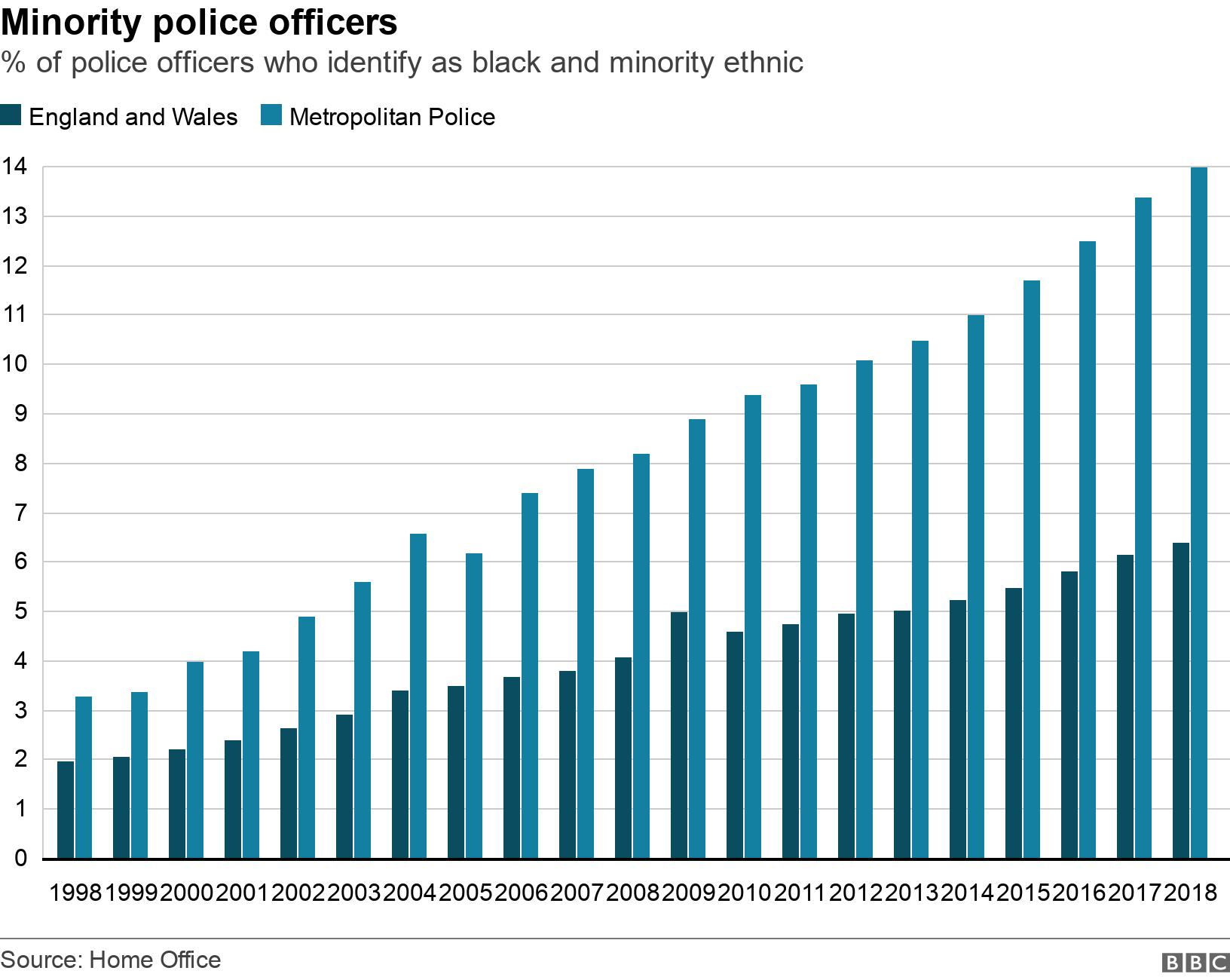

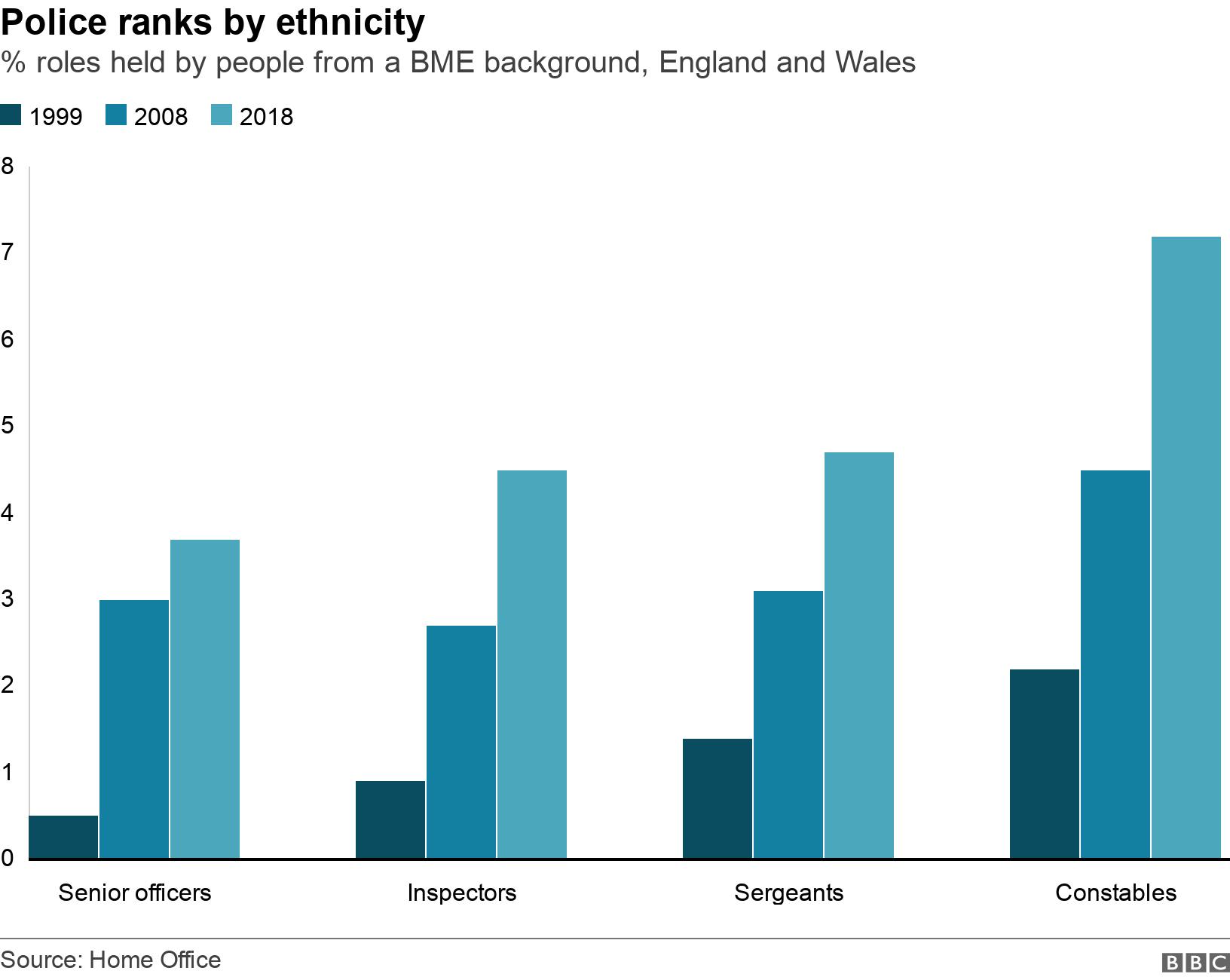

The inquiry called on the Home Office and police forces to develop initiatives to increase the number of ethnic minority officers and to set targets on their "recruitment, progression and retention". In 1998, only 2% of officers in England and Wales were from a BAME background.

The aim was to raise that to 7%, overall, by 2009 - but that proved to be too ambitious and it's only in the past year that the target has been reached, by which time the overall BAME population has risen to about 14%.

Each force was given its own individual target and in many constabularies, the Met included, BAME communities remain under-represented, though there's greater diversity among new recruits and police community support officers - a role introduced in 2002.

Further up police ranks, and in specialist units such as firearms, the shortage of BAME officers becomes more acute. In the history of the service, there has only been one ethnic minority chief constable - Mike Fuller, who led Kent Police between 2004 and 2010.

There are currently no more than a handful of BAME officers in senior roles, raising serious questions about efforts to mentor and encourage ethnic minority officers to stay in the service and apply for promotion.

In 2009, in its 10-year Macpherson anniversary report, MPs on the Home Affairs Select Committee said progress had been "slowest" in the police workforce itself. A decade on, the evidence suggests that is still the case.

Additional research by Ben Butcher