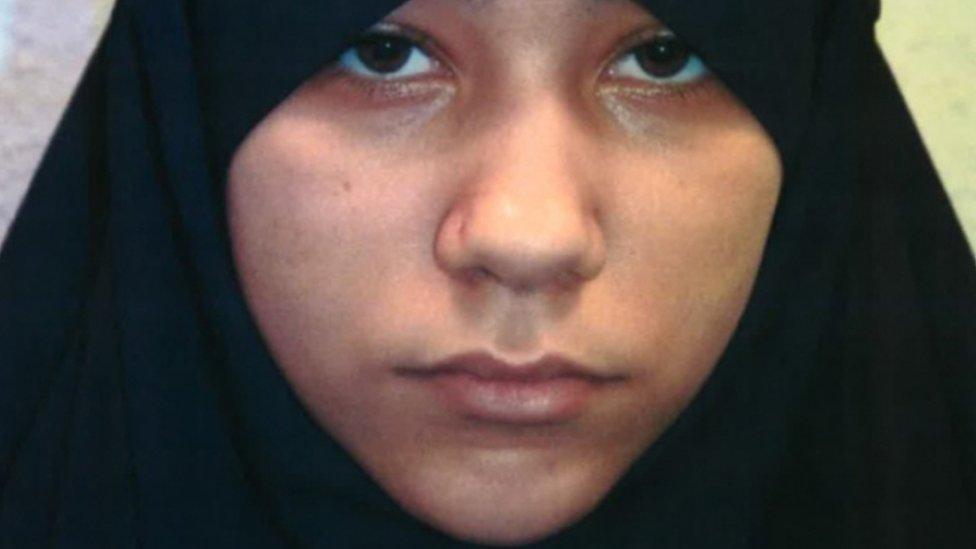

Shamima Begum: What can the UK do about the IS teenager?

- Published

"I'm not the same silly little schoolgirl who ran away four years ago," Ms Begum said

Shamima Begum, one of three schoolgirls who left London in 2015 to join the Islamic State group, has said she wants to return to the UK. But what problems does that throw up?

Who is Shamima Begum - and what did she do?

Shamima Begum is from Bethnal Green in east London and left home in 2015 at the height of the power of the self-styled Islamic State group in Syria and Iraq.

She and two friends - Amira Abase and Kadiza Sultana - flew from Gatwick Airport to Turkey after lying to their parents about their plans for the day. Their aim was to join another friend, Sharmeena Begum, who had left in late 2014.

The trio were picked up by smugglers working for the IS group and taken across the border into the group's territory in northern Syria. Once there, they were to be married off as jihadi brides to the foreign fighters who had flooded in from across the world. The group aimed to raise a new generation of children supporting its so-called caliphate - and grooming young women to the cause was key to that plan.

Anthony Loyd of the Times describes how he found Shamima Begum in a Syrian refugee camp

Like other British young women, she was first kept in a house with more prospective brides. Evidence from other cases has revealed that these guest houses were used to further indoctrinate the women with the group's ideology and prepare them for their new lives. Once a suitable match was found, the women were married off one-by-one.

All the Bethnal Green group were given husbands. Kadiza Sultana was reportedly killed two years ago following an airstrike on Raqqa.

Shamima Begum's fighter husband is reported to have been Yago Riedijk - a Dutch English-speaking convert. In her interview with the Times, she says their first two children died of complications linked to both malnutrition and a lack of drugs inside the war zone.

They fled Raqqa as the air strikes worsened, and as the militant group's territory shrank, the couple - now expecting their third child - were squeezed into the last IS stronghold. Eventually the teenager gave up and headed to a refugee camp.

How much of an extremist is she?

When the teenager and her friends ran off to Syria, their families and the security services were hoping that they had been groomed and brainwashed, but would come to their senses and attempt to find some way out.

Amira Abase, Kadiza Sultana and Shamima Begum at Gatwick Airport in 2015

But the security services in London were also deeply concerned that the girls would be a propaganda tool to help IS recruit others from their community. Five more teenage girls who were suspected of being groomed alongside Ms Begum and her friends were subjected to family court action to control their movements and care. They can't be named for legal reasons.

From the tone of Shamima Begum's Times interview, external, she does not appear to regret her decision. She describes being unfazed by seeing the decapitated head of an anti-IS fighter, whom she described as an "enemy of Islam".

Can she return to the UK?

In the short term, no. The British government has no consular staff to help her in Syria. Ministers won't order personnel to risk their lives to help out someone who joined a banned terror group.

But suppose she got out of the refugee camp and crossed into Turkey. Could she just get on a flight home?

Almost certainly not. She may not have any travel documents - IS recruits were forced to hand over their passports and, in fact, some burnt them as a sign of their allegiance to the self-styled state.

The Home Office is able to cancel passports to prevent people moving freely - this is a well-used counter-terrorism tactic to prevent fighters crossing borders. It's not known whether it has happened in this case.

The UK has the power to strip Ms Begum of her nationality, providing she is not left stateless. This seems unlikely because she was not a fighter.

If she did reach a safe location, security chiefs in London could control any possible return through a Temporary Exclusion Order.

This controversial legal tool - which was used nine times in 2017 - bars a British citizen from returning home until they have agreed to investigation, monitoring and, if required, deradicalisation.

Does the UK have duties to her because of her age?

Shamima Begum was legally a child when she went to join Islamic State. And if she were still under 18 years of age, the government would have a duty to take her "best interests" into account in deciding what to do next.

But she is now an apparently unrepentant adult, and if she wants to come back she would have to account for her decisions and face possible prosecution, even if her journey is a story of grooming and abuse.

She says she is nine months pregnant. If her baby is safely delivered and she then wants to return to the UK, that is a slightly different and more complex issue.

Ms Begum was 15 when she left the UK in 2015

Assuming that Ms Begum is still British, her child would be too. And that would trigger legal duties to take into account the baby's welfare.

That doesn't mean that the UK would risk the lives of security service personnel to get her out - far from it.

But social services would almost have to take a view about what to do with mother and daughter if they were able to return.

According to the latest figures, since 2015 about 100 children in England and Wales have been "safeguarded" by the family courts from being taken to conflict areas in Syria and Iraq.

This involves each child becoming a "ward of court" - meaning a judge makes decisions about their future - or they are removed from their families and placed into care. Some of the cases have involved evidence that a parent was brainwashing the child. So Ms Begum's mindset would be critical in any decision about the future of her child.

Would Shamima Begum be prosecuted?

The UK's specialist counter-terrorism prosecutors vigorously pursue anyone with a link to dangerous groups who has not satisfactorily accounted for their actions. There would be a strong public interest to do so - and there is also a precedent.

Tareena Shakil from Burton-upon-Trent is another British jihadi bride who got out of the war zone.

Intelligence services established she had been married off - but she lied about this when she left to return to the UK with her child - and was subsequently jailed for membership of a terrorist group.

That is exactly the kind of prosecution that Ms Begum could face if she returned - along with encouraging or supporting terrorism.

But that is a long, long way off.

If Shamima Begum did get back to the UK, she would be subject to the closest possible scrutiny. Irrespective of a prosecution decision, she would be offered the chance to enter into a deradicalisation programme.

A government-approved "intervention provider" would work with her to challenge her thinking and beliefs. These are highly trained experts in theology, psychology and other specialisms that are called upon to break the mental hold that a cult has over its recruits.

This work is very hard - and not always successful.

But the intervention providers would almost certainly be the only experts able to advise counter-terrorism chiefs whether Shamima Begum could ever readjust to a normal life.

Who has returned from Iraq and Syria?

More than 40,000 citizens from 80 countries have become affiliated with the Islamic State (IS) group in Iraq and Syria, according to the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation's 2018 report, external.

Of the roughly 5,000 Europeans who departed to join IS, about 1,200 are estimated to have returned, according to a 2018 European Parliament report, external.

The report breaks down figures for six countries. France accounted for the highest number of those that travelled to Iraq and Syria (1,910), followed by Germany (960), and the UK (850).

The proportion of people that have returned varies. Half those that left the UK have returned, the highest rate among the six countries examined in the report. About 30% have returned to Germany and Belgium and just 12% to France.

Across EU countries, dealing with the returning fighters is primarily based on criminal investigation and risk assessment. Rehabilitation and reintegration schemes have been introduced inside and outside prison.

Other measures include restrictions on movement and powers to withdraw or refuse to issue passports.

The radicalisation of Safaa Boular: A teenager's journey to terror

Safaa Boular was one of the youngest people accused in the UK of terror offences. Last year she was given a life sentence for plotting an attack. Alongside her mother and sister, who were also jailed, Boular was part of the UK's first all-female IS cell.

Read more: The radicalisation of Safaa Boular: A teenager's journey to terror (2018)

- Published14 February 2019

- Published23 March 2019

- Published13 December 2018

- Published4 June 2018

- Published1 February 2016

- Published26 March 2015