The footballer, the Saudi prince and the proposition

- Published

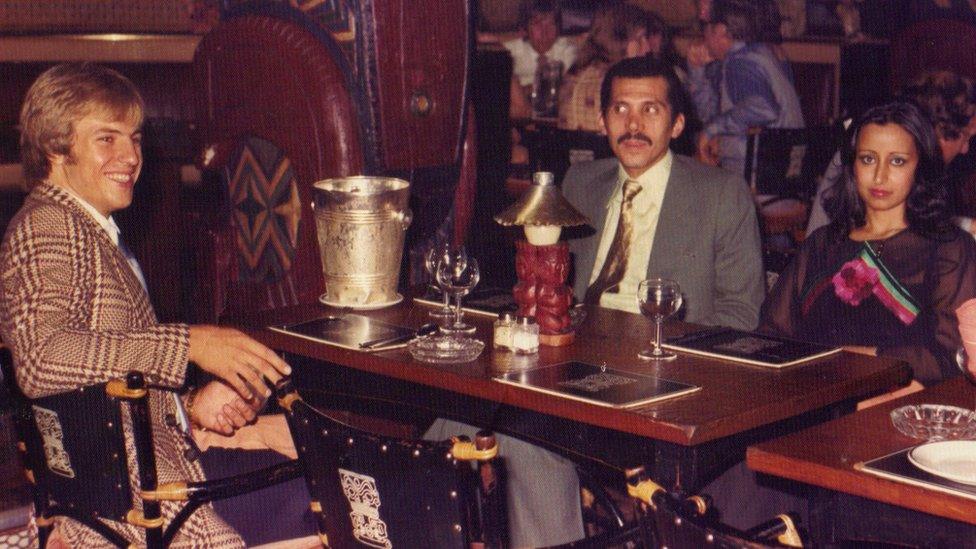

Eamonn O'Keefe, Prince Abdullah bin Nasser and one of the prince's wives at the Barracuda restaurant in London in 1976

The Grand Hotel, Cannes, 1976. On a hot summer night, a rich man and a poor man stand in a lift.

The rich man is Prince Abdullah bin Nasser: grandson of the founder of Saudi Arabia; son of the ex-governor of Riyadh; rich beyond imagination.

The poor man is Eamonn O'Keefe: footballer from Manchester; son of a print worker; owner of a terraced house in Oldham.

The men are coming back from the casino. Abdullah has lost - he always lost - but no matter. If you're a Saudi prince, a few thousand dollars is lunch money.

Eamonn doesn't gamble, but he has won. Two years earlier he was a reserve at Plymouth Argyle in the third tier of English football, trying to find coins for the electricity meter.

Now, he's flying with the jet set: first class planes, five-star hotels, on a grand tour of Europe with one of the world's richest families.

And then, in the lift, Abdullah turns to Eamonn.

"I've been meaning to tell you something," says Abdullah. He puts his hand on Eamonn's shoulder. "I am finding that I love you."

Eamonn can smell the prince's breath; cigarettes and Johnnie Walker whisky. Nervously, he replies. "You mean - like a brother?"

"No," says Abdullah. "Not like a brother."

And that, on a hot summer night in Cannes, is where the trouble began.

Eamonn (front left) pictured with the Manchester Boys team. "I broke my leg 15 minutes after this was taken"

Eamonn, who's now 65, grew up in post-war Britain, in a three-bedroom, semi-detached council house in Blackley, north Manchester. He had three brothers, two sisters, and a dog. Gran lived with them too. Where did they all sleep?

"I'm still baffled," he says in a Manchester hotel, smiling at the memory.

His dad, an Irishman, ran the St Clare Catholic men's football team. His mum washed and ironed the kit; Eamonn fetched the balls, then waxed them with dubbin before the next match.

Eamonn's house was 30 yards from the park and he would play there, on the wet Manchester grass, until it got dark. He was a fine footballer: picked for Manchester Schools and Manchester United's youth team until, in a match against Altrincham, he broke his leg.

His dream - playing under the lights at Old Trafford - was over. Instead, he left school and worked as an errand runner for the Manchester Evening News.

When his leg was better, he signed for Stalybridge Celtic, a semi-professional club nearby. His first manager was George Smith, an ex-player who was building an international coaching career.

George - who had already worked in Iceland - left Stalybridge to manage Al-Hilal, one of the biggest clubs in Saudi Arabia. Soon afterwards, Eamonn left too, moving 300 miles south to sign as a professional for Plymouth.

But he was miserable there - his wages barely covered the rent - and he lasted less than a season. Then, after coming home, he received a letter.

The postmark was in Arabic.

Eamonn, who still lives in north-west England, revisiting one of his former streets in Manchester

The letter was from George Smith. He wanted Eamonn to fly to Saudi for a month's trial. If he impressed - and could handle the heat - he would become Al-Hilal's first European signing.

"It was November, I think it was snowing [in Manchester]," says Eamonn. "I thought - 'That's not a bad shout.'"

But it wasn't just the weather that appealed. Eamonn was married with two children: a spell in Saudi, he thought, would mean repaying the mortgage on his house sooner than he thought.

He went to London and flew to the Saudi capital, Riyadh, via Cairo and Jeddah. On arrival in Jeddah, he knew he was in a different world. A Saudi official took his Sunday Express, got a pair of scissors, and cut out the pictures of women, leaving only their heads.

It could have been worse, says Eamonn: the man next to him had the News of the World.

The culture shocks kept coming. In Riyadh, George waited for Eamonn on the runway, sitting on the bonnet of a huge Buick. At home, Eamonn drove a Morris Mini estate.

In Manchester, fish and chips were a treat. At the five-star hotel, Eamonn signed for free food and drink.

Eamonn - a 22-year-old from a council house - was in an alternative universe. It wasn't just the heat, or the palm trees or the shimmering desert that stretched to the horizon. It was the wealth.

The formation of Opec in 1960, and the oil crisis of 1973, meant the Saudi economy was booming. Between 1970 and 1980, the country's economy rocketed by more than 3,000%. It was wallowing in oil, and serious men had serious money. Eamonn was about to meet one of them.

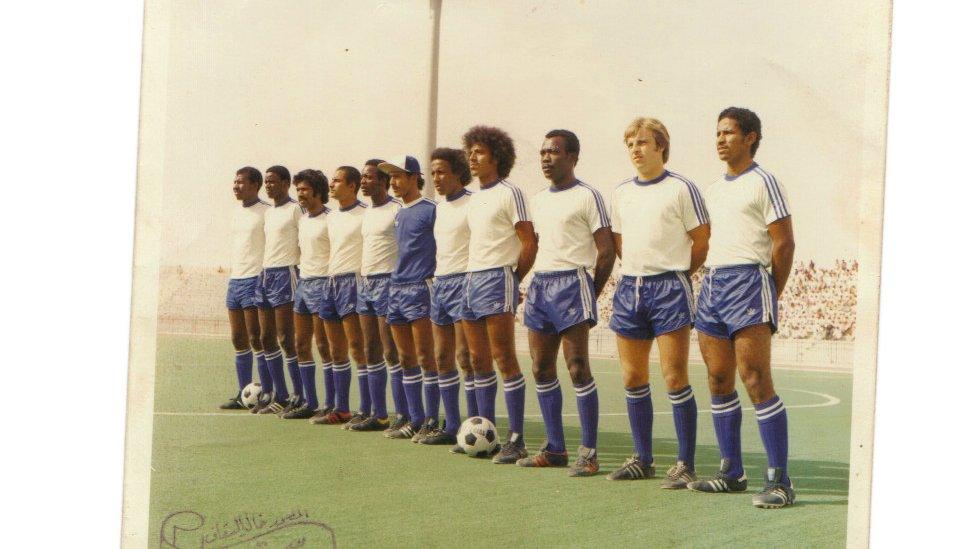

Eamonn O'Keefe (second right) playing for Al-Hilal in Saudi Arabia in the 1970s

Eamonn first saw Prince Abdullah bin Nasser at Al-Hilal's training ground in Riyadh.

Still on trial, he was playing a practice game when Abdullah, the club president, pulled up in a blue Buick. From the pitch, Eamonn saw a pair of eyes peering through the rolled-down window.

"George said: 'See the car over there? That's my laddo - the president. He says yes or no [to the contract]. So sharpen up!'"

Straight away, the ball came in from the right wing. Eamonn's eyes lit up. He leapt, blond locks bouncing in the desert air, and headed the ball towards goal.

"It bulleted into the top corner," he says, more than 40 years later. "And I mean bulleted."

Five minutes later, the ball came in from the left wing. Again, he leapt. Again, the ball hit the top corner. As they waited to re-start the game, George whispered in Eamonn's ear.

"Whatever you were thinking," he said, referring to Eamonn's wage demands, "add another nought on."

After the match, Eamonn, still in his sweat-drenched kit, went to meet the prince. Abdullah asked if the hotel was OK; Eamonn said it was. Abdullah asked if George was happy; George said he was.

"Then go to the hotel and write down your needs," said the prince.

Eamonn and George made a list: money, car, apartment, flights to England and private schooling for Eamonn's two children when they were old enough. At the next training session, the blue Buick pulled up. George gave Abdullah the list.

"Not a problem," the prince said.

At home, Eamonn earned £40 a week, plus £15 playing football. His new weekly wage was around £140 - equal to £1,100 today, according to Bank of England inflation data. There were no taxes, no bills and no worries.

With his contract agreed, Eamonn flew back to Manchester, packed his bags and returned to Riyadh with his family. At first they lived in a hotel, and - as before - paid for nothing.

"The bill was staggering, but it was never questioned," says Eamonn.

His wife took a well-paid job at the First National City Bank, and, as Al-Hilal trained only twice a week, Eamonn passed his time by the pool, looking after the children, talking football with George. They were blissful days in the desert. "I can still see the kids with the floats on," he says.

From the start, Abdullah liked Eamonn. He bought him a car - "a silver Pontiac Ventura, bonnet like a runway" - and often invited him over for tea. They watched football on a big screen (a luxury in 1976) or talked to Abdullah's brothers.

It was an unlikely set-up - a blond-haired boy from England welcomed into the Saudi royal court - but Eamonn enjoyed it. He was young and confident, and found the Saudis surprisingly down-to-earth and kind. In some ways, it was like Manchester - except here, his friends ran the country.

On the pitch, things also went well. Eamonn liked his team-mates, and the team reached the semi-final of the King's Cup (before losing on penalties to rivals Al-Nassr). Saudi Arabia wasn't perfect - Eamonn once drove into a square where a public flogging was taking place, with his children in the back seat - but life was good.

When the season ended, the O'Keefes returned to England for a holiday. Before they left, Abdullah asked for Eamonn's home phone number.

"I'm also planning a trip to England," said the prince. "We should meet up."

Eamonn was the first European professional to play in the Saudi league

After three weeks in England, Abdullah phoned Eamonn's mother's house, where the O'Keefes were staying. Eamonn was out so his mother took the call.

"What's-he-called has been on the phone," she told her son. "That prince fella."

Eamonn called Abdullah back - reverse charges - at the Carlton Tower, a hotel near Harrods in London. Two days later he was on a train to Euston. A chauffeur met him at the station.

In the capital, Eamonn was again riding on a merry-go-round of Saudi money. He watched as the prince bought six Cecil Gee suits and wondered, in the Grosvenor Hotel, why a man with white gloves stood near the urinals. ("I honestly thought - he doesn't hold it for you, does he?").

When one of Abdullah's assistants needed new shoes, Eamonn was given £200 and sent to buy a pair. He gave back £150 and went to Marks & Spencer.

"Different world," says Eamonn.

Soon afterwards, the same assistant returned to Riyadh, so Abdullah asked Eamonn if he wanted to take his place on the tour. It was Paris next, followed by Cannes, Rome, Cairo and back to Saudi. Abdullah's wife wanted to buy furniture; the prince planned to roll the dice at Europe's casinos.

His wife and children were going to Wales with his mother-in-law, so Eamonn agreed. A week later, he was in a limousine to Heathrow, ready for his grand tour with "Prince What's-He-Called".

By now, the Saudi prince and the boy from Blackley were friends. Eamonn and Abdullah: the Unlikely Lads.

"We got on great, we were laughing all the time," says Eamonn. "I think he was bored with all these [other] fellas sucking up to him."

At Charles de Gaulle airport, the Saudi ambassador met the prince and his party. "Flags on the car, all that," says Eamonn.

While Abdullah held meetings, he gave Eamonn a case to look after. Eamonn got coffee and a bar of chocolate, waited in the VIP area, and was eventually taken to Paris alone, case in tow.

An hour later, the phone rang in his hotel room. It was Abdullah, asking for the case, so Eamonn went downstairs to the prince's suite. The prince flipped the locks and showed Eamonn what he'd been carrying: thousands upon thousands of French francs.

"A bit like you see on telly, when there's no room for anything else," says Eamonn. "I left it on the seat when I got coffee at the airport - can you imagine if I'd lost it?"

That night, Eamonn dined in a glass-bottomed boat on the Seine, before admiring the city from his hotel balcony. He fell asleep a happy man. But his sweet dreams didn't last.

Two days later, they flew to Cannes, where they went to the casino and rode in the same lift.

Eamonn with his car in the Saudi desert

After Abdullah made his move, the lift suddenly felt smaller, says Eamonn.

The prince had made his feelings clear, so Eamonn did too. He wasn't gay. He wasn't interested in a relationship. He wanted to be a footballer, and nothing else.

"It was probably 15 seconds [until the lift doors opened]," says Eamonn. "But it felt like a month. There was this horrible coldness."

At that moment, the grand tour was over. The atmosphere had changed, and so had the itinerary. Instead of three nights in Rome, they had one; instead of stopping in Cairo, they went straight to Riyadh.

"It was like ice," remembers Eamonn.

Eamonn was embarrassed, but he wasn't worried. In the lift, Abdullah told him their relationship would return to "president and player", and Eamonn believed him.

"I was not thinking for a minute I was in any danger," he says. "I thought - I've got my contract, we'll get back to normal."

After getting back to Riyadh, that changed. Homosexuality was - and still is - illegal in Saudi Arabia, and the royal family were - and still are - omnipotent. Eamonn wasn't going to reveal Abdullah's secret - but what if Abdullah wanted to apply some pressure?

Eamonn felt worried. Claustrophobic. Paranoid, perhaps. He went to tell George what had happened, to seek reassurance. He didn't get it.

"They're not going to leave it at that, you idiot," said George.

George Smith is 84 now; still watching football and still bursting with stories from a long coaching career. Does he remember Eamonn? "Oh yes," he says on the phone from Rochdale. "I made him a pro."

George's tales bounce from Saudi to Iceland, via Oman and Bahrain. But Eamonn sticks out. He liked him, but even before their grand tour he was worried. Eamonn spent too much time with Abdullah, he thought - and Abdullah spent too much money on Eamonn.

"I thought they were too close, and the president [Abdullah] knew it," he says. "He knew I was worried about it."

When George heard about Cannes, he told Eamonn to leave Saudi for his own safety. "He was in danger," he says. "Anything could have happened."

Such as?

"God knows. An accident of some sort. He was interfering with royalty [Abdullah] - you can't do it."

Eamonn went cold. He knew a secret about one of the most powerful men in the country, and that - he thought - put him in danger. He spent the night on George's sofa, but passed most of it staring at the ceiling. He was 22 years old, far from home, and scared. His family were in England, and he couldn't let them return to Riyadh.

But there was a problem.

To leave the country, his boss had to sign his exit visa - and his boss was Prince Abdullah. To Eamonn, Saudi always felt gilded. Now, it felt like a gilded cage.

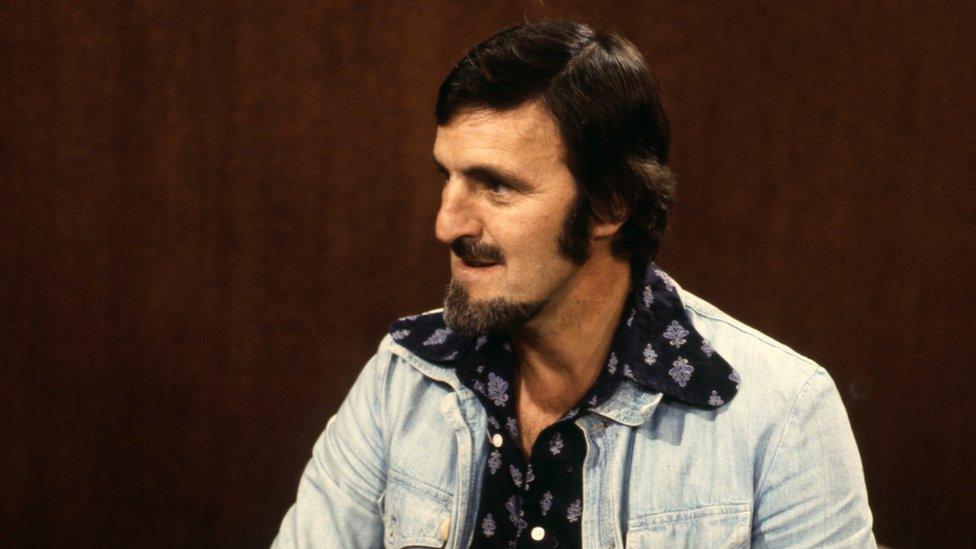

Jimmy Hill, pictured on the Parkinson show in 1976, was involved in releasing Eamonn from his Saudi contract

The next morning, Eamonn decided to lie.

He would tell Abdullah that his father was ill, and he needed to see him in England. He went to Abdullah's mansion, told his story and waited for a reaction. The prince listened but made no decision. Instead, he made him sweat. They would discuss it tomorrow, Abdullah said.

It was another long night. The five-star hotel in Paris, when he'd slept without a care in the world, seemed a long time ago.

The next day, Eamonn went to the football club to meet Abdullah. The prince closed the door and told his staff not to disturb them. Eamonn remembers the prince sitting at the head of a large table.

"Is this because of France?" the prince asked. "I don't believe you will return."

As Eamonn tried to persuade Abdullah, the prince reached for a pen and paper. Slowly, Eamonn says, he started writing in Arabic. It was a deal. Eamonn could go home, but only for a week.

All he had to do was sign.

Eamonn couldn't read Arabic. For all he knew, he was signing his life away. So he couldn't sign it.

But he couldn't rip it up, either. If he did, the prince would never let him go. He thought, quickly, and decided on what he now calls "the Bluff of the Year".

"You want me to sign this?" asked Eamonn. "I have to trust this contract in Arabic - but you don't trust me back? OK, not a problem."

Eamonn took the pen and went to sign. At the last second, Eamonn says, Abdullah snatched the paper, ripped it up, and threw it in the bin.

"I will arrange a flight for you," he said, reluctantly.

The next day, Eamonn went to the airport. He took only a week's clothes, so Abdullah didn't think he was leaving for good. Was he still scared?

"Absolutely," says Eamonn. "Because if he [Abdullah] says you're not getting on the plane, you're not getting on it. Even when the plane went up, I was worried."

After he landed in London, he punched the seat in front with joy. But his problems weren't over. To resume his career in England, he needed to register with the Football Association. To register with the Football Association, he needed clearance from Saudi Arabia.

After speaking to the FA, Eamonn received a fax from Riyadh. It demanded:

-9,000 Saudi riyals for breaking the contract (around £1,200 then, equal to £8,000 today)

-1,500 riyals for repairing the air conditioning at his apartment

-£300 (in sterling) to repay a loan from Abdullah

-Minus one month's salary still owed to Eamonn

Eamonn could accept points one and four. The others, he felt, were revenge by Abdullah. The air conditioning wasn't broken, he says, and he never borrowed a penny from the prince.

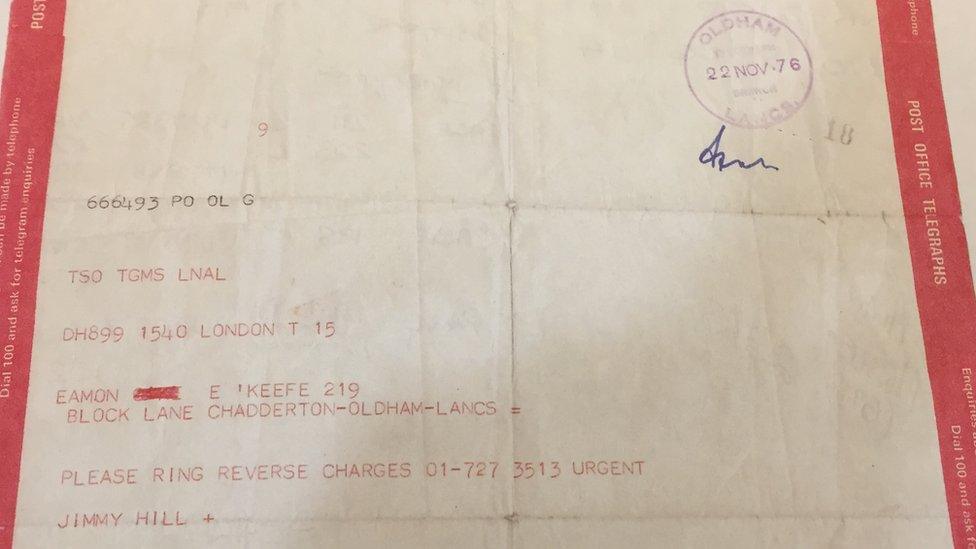

Eamonn spoke to the FA and, on 22 November 1976, received a telegram from London. "Please ring - reverse charges - urgent," it said. It was signed by the new head of Saudi football, Jimmy Hill.

Jimmy Hill's telegram to Eamonn

In 1976, Jimmy Hill was one of the most famous men in English football. In 1961, as head of the players' union, he had abolished the maximum wage; by the 1970s, he was presenter of the BBC's primetime football show, Match of the Day.

The contract in Saudi was worth £25m. How much went to him and his son Duncan (also employed in Saudi) is unknown, but it was too much to be blown by a boy from Blackley.

As requested, Eamonn phoned Hill. Eamonn's dad - a trade unionist - said he was happy to tell Fifa, and the world, what happened in Cannes. Two weeks later, a meeting was arranged in Altrincham between a mutual friend of George and Eamonn's, a representative from Al-Hilal, and Eamonn.

"What do you think would have happened if you stayed?" asked the man from Al-Hilal, sarcastically.

"When it's your family, you can't gamble," Eamonn replied, deadly serious.

After a heated discussion, the men shook hands. A week later, the Saudis sent Eamonn's release, and he was free to play in England. The Saudi adventure was over. Finally, he was off the merry-go-round.

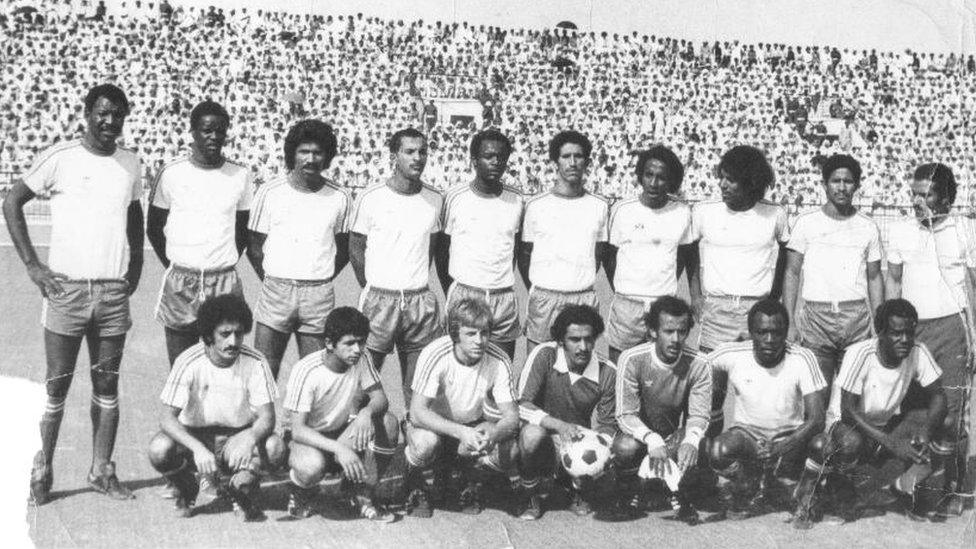

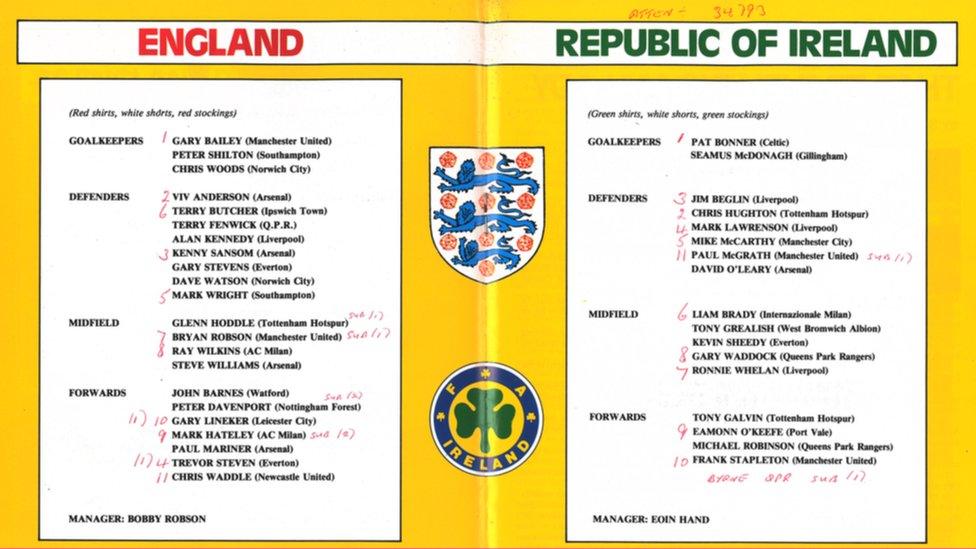

Eamonn rebuilt his career to the extent that he was picked to play for the Republic of Ireland against England at Wembley (number nine in the Irish side)

When he got back to England, Eamonn was broke.

He couldn't get his wages - they were in a Saudi account - so he had to sell his house in Oldham. He returned to work at the Manchester Evening News, and, eventually, started playing for semi-professional side Mossley.

After the sunshine and swimming pools of Saudi, the wind and rain of the Northern Premier League seemed like a step down. But Eamonn loved it.

In 1979, Mossley won the league and cup double and Eamonn moved to Everton, in the top tier of English football, for £25,000. He played 40 times in the First Division before moving to Wigan Athletic. He also played five times for the Irish Republic - including, in 1985, against England at Wembley.

The last time he had been there, in 1968, he was a wide-eyed fan watching Manchester United beat Benfica in the European Cup final. Now, people were paying to watch him. It is one of many reasons why he isn't bitter about Saudi, Abdullah or that hot summer night in Cannes.

"If it [the incident in the lift] hadn't happened, I would have stayed in Saudi," he says. "I might never have played for Everton, might never have played for Ireland."

Eamonn is now retired near Manchester, but still works part-time for Everton FC

Abdullah remained as president of Al-Hilal until 1981, and kept spending. After Eamonn, his next signing was Rivellino, the Brazilian World Cup winner. The club won the new Jimmy Hill-organised league in 1977 and 1979, and are now one of the biggest clubs in Asia.

Apart from his love of football, not much is known about the prince. The Saudi government's Center for International Communication and Al-Hilal Football Club both declined to comment on Eamonn's story, and there has been little written about the prince. He was, after all, one of hundreds.

Abdullah's grandfather - Ibn Saud, the founder of the country - had 45 sons. Of those, 36 had children of their own, one of whom was Abdullah.

As one Saudi expert told the BBC: "These guys lead very sheltered lives, in a society which has the opposite of an enquiring press."

The Saudi government wouldn't say whether Abdullah was alive, but the Al Hilal website suggests he is dead. A Middle East journalist told the BBC he passed away in 2007, another thought it might be 2006.

According to Arabic Wikipedia - the entry runs to less than 400 words - Abdullah had three wives and seven children. The last time Eamonn saw him was the "Bluff of the Year" in Riyadh.

You may also be interested in

After managing Cork City in Ireland, Eamonn worked for the council in Cheshire. He moved to Portugal but is now retired near Manchester. He was treated for cancer in 2017 with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and is making a steady recovery.

"Touching wood and sending up a quick prayer, it's all looking good now," he says.

He still works on match days in the hospitality suites at Everton, sharing stories from his career. For years, he didn't talk about Saudi: he didn't want to relive the trauma, or open himself to homophobic taunts. After coming home, he even turned down a cheque from a tabloid reporter.

But now, more than 40 years on, he is happy to share all. More than anything, he wants his Saudi team-mates to know why he left.

"I loved my time in Saudi - how can you not love living like that?" he says. "I loved my team-mates, the facilities were great, the whole set-up was fantastic. We were happy there."

Eight years ago Eamonn wrote an autobiography. Its title perfectly captures his life, from the green grass of St Clare's Catholic club to his red-hot Saudi adventure.

I Only Wanted To Play Football.

Photographer: Jon Parker Lee

- Published13 January 2019

- Published9 January 2018

- Published3 April 2019