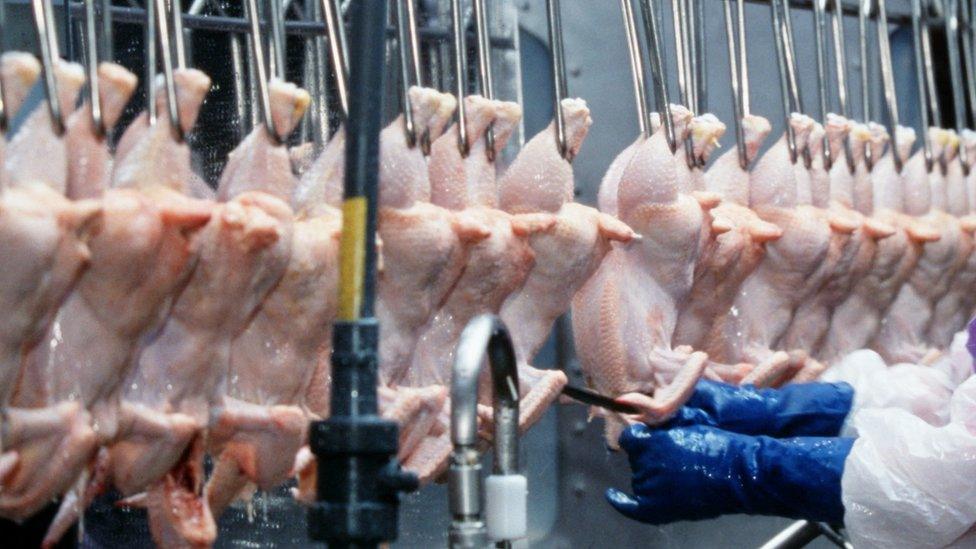

Chlorinated chicken: How safe is it?

- Published

Fears over chlorine-washed chicken and other US farming practices have been described by US ambassador to the UK Woody Johnson as "inflammatory and misleading".

Mr Johnson urged the UK, external to embrace US farming methods after Washington published its objectives for a UK-US trade deal. He said the process was used by EU farmers to treat vegetables, and that it was the best way to deal with salmonella and other bacteria.

So is it safe? The evidence suggests the chlorine wash itself is not harmful. But the concern is that treating meat with chlorine at the end allows poorer hygiene elsewhere in the production process.

Why ban chlorine-washed chicken?

Washing chicken in chlorine and other disinfectants to remove harmful bacteria was a practice banned by the European Union (EU) in 1997 over food safety concerns. The ban has stopped virtually all imports of US chicken meat which is generally treated by this process.

It's not consuming chlorine itself that the EU is worried about - in fact in 2005 the European Food Safety Authority said that "exposure to chlorite residues arising from treated poultry carcasses would be of no safety concern, external". Chlorine-rinsed bagged salads are common in the UK and other countries in the EU.

But the EU believes that relying on a chlorine rinse at the end of the meat production process could be a way of compensating for poor hygiene standards - such as dirty or crowded abattoirs.

Instead, the EU says the best way to eliminate the risk of salmonella and other bacteria is to maintain high farming and production standards.

The European Commission says: "This rule is part of wider EU legislation ensuring a high level of safety throughout the food chain, from farm to fork."

The US has voiced frustration, saying the ban is not based on scientific evidence. It even tried to bring a case before the World Trade Organization in 2008, external.

Does US meat have more harmful bacteria?

The US Department of Agriculture's (USDA) National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System tests samples of raw chicken from shops for bacteria.

In its most recent round of testing it found a significant amount of the bacteria campylobacter - the most common cause of food poisoning - in 30% of chicken carcasses, 26% of chicken parts and 58% of "mechanically separated" chicken, which is used to make things like chicken nuggets.

It recorded how much of the chicken had more than 400 units of bacteria per gram of meat.

In the UK, the government's Food Standards Agency found 54% of chickens had traces of the bacteria but only 6% had the highest levels - more than 1,000 units of bacteria per gram of meat.

Since they don't measure exactly the same thing, it's difficult to compare these results.

Chlorine does reduce the bacteria on chicken, although by how much is disputed - the World Health Organization has highlighted that studies on the effectiveness of chlorine treatment give mixed results, external.

A study from the University of Southampton, external last year found that chlorine could make food-borne pathogens undetectable, giving lower microbial counts in testing, but without actually killing them - so they might remain capable of causing disease.

So is food poisoning more common in the US?

Comparing levels of illness in different countries can be tricky. But there are different studies, from the US and the UK, which try to estimate the overall rate of food poisoning and adjust for the levels of underreporting in each health system.

The average American consumed 42kg of chicken in 2018, according to data from the National Chicken Council

A study published in the UK in 2014, external commissioned by the government estimated that there were about 34,000 cases of salmonella from food per year or about 55 per 100,000 people, based on 2009 data. A US study published in 2011, external - and using data from 2002-2008 - estimated that there were just over a million cases of salmonella each year - a rate of about 350 per 100,000 people.

For campylobacter, the UK study estimated 280,000 cases - about 450 cases per 100,000 people. The US study estimated 845,024 cases of campylobacter or about 300 cases per 100,000 people.

But it is hard to make comparisons between two different studies that use different methodologies.

The World Health Organization tried to estimate global rates of sickness, external from food in 2015. It gave data for regions rather than individual countries.

Data used for the study suggests that the region containing the US, Cuba and Canada has a higher rate of salmonella but a lower rate of campylobacter than the region containing developed European countries including the UK.

Lots of people also don't go to their doctors with symptoms of food poisoning, so in both the US and the UK only the more severe cases of food poisoning will come to the attention of authorities.

It may be that a higher proportion of people are infected but only certain groups - the very old and young, for example - will actually end up being diagnosed and treated.

Not all food poisoning is from meat, though - although poultry is the most common cause - and not all food poisoning is down to the production process. Some bacteria will generally be left on the skin of a chicken so the care with which it's handled and cooked at home are extremely important.

Clarification: This piece was amended on 5 April to add more statistics and context.