Knife crime: Are school exclusions to blame?

- Published

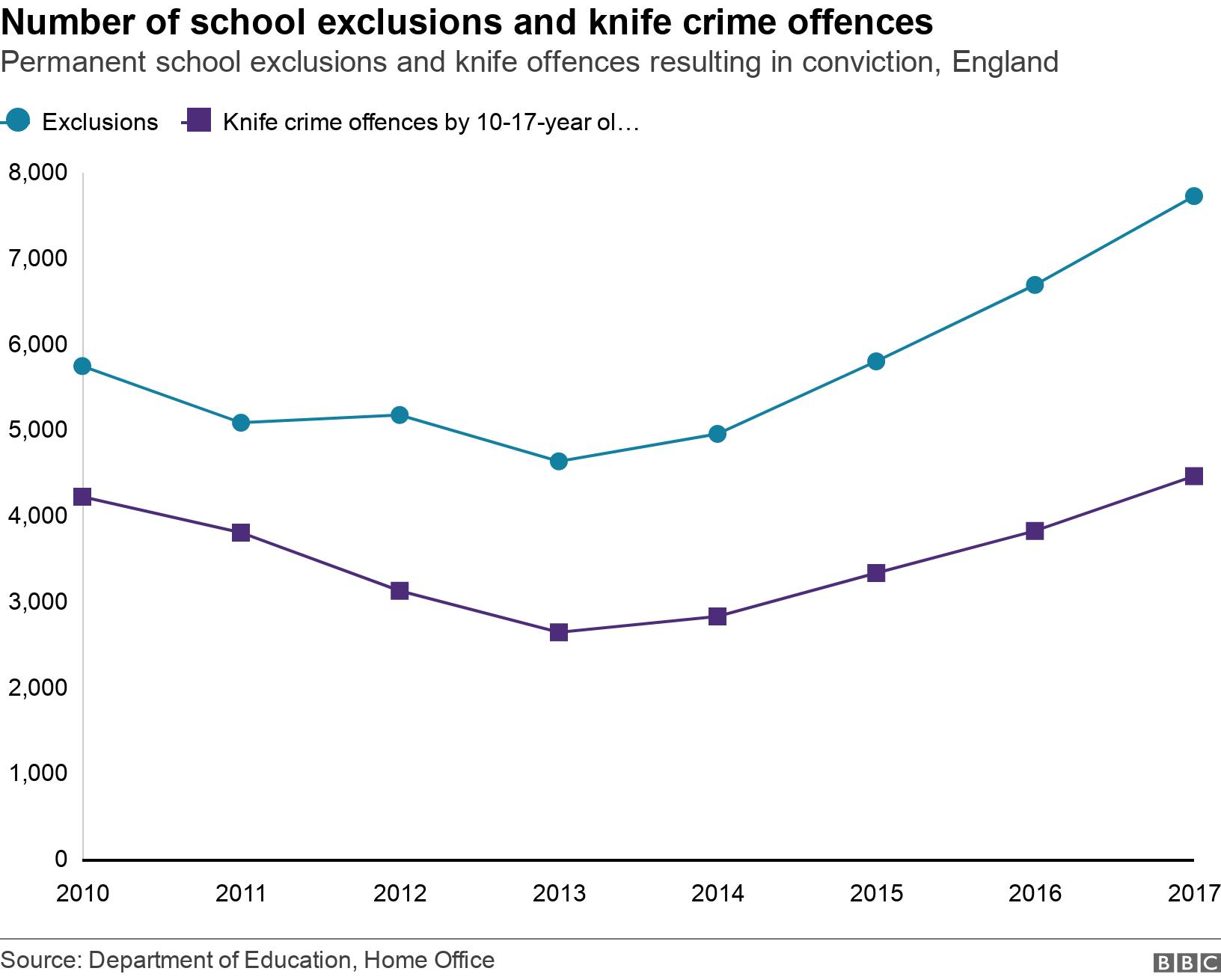

Permanent school exclusions in England have been rising since 2013, and so has the number of children being arrested for knife offences.

Almost a quarter of children in England who said they had carried a knife in the previous year had been expelled or suspended from school. Only 3% of children who said they had not carried a knife had been excluded, according to government figures., external

Police commissioners have written to Theresa May to warn that children who are excluded from school are at risk of being "sucked into criminality".

So are school exclusions driving a wave in youth crime?

There is certainly a close correlation between school exclusions and knife crime in young people. As one goes up, the other goes up and vice versa.

But this doesn't tell us that school exclusion in itself is causing knife crime. Other things have been increasing at the same time which could be driving both trends, including rising child poverty, mental ill health and rising numbers of children considered by local authority social services to be "in need".

In a 2017 report on rising school exclusions, external for centre-left think tank the Institute for Public Policy Research, researcher Kiran Gill said that rising exclusions could be partially explained by rising numbers of children with complex needs and vulnerabilities.

There are lots of common factors in the lives of children who get excluded from school and children who become involved in knife crime. These include poverty, family instability and special educational needs.

In England, four times as many children who had committed knife offences, and seven times as many children who had been excluded from school, had special educational needs, compared with the rest of the pupil population, according to data from 2015.

Both were about four times as likely to be claiming free school meals - which are available to lower-income households. And the rate of permanent exclusion in the most deprived 10% of schools was double that of the least deprived.

The discussion around school exclusions comes as disagreements continue over the connection between police funding and violent crime.

There are 20,000 fewer police officers now than there were in 2010 and funding has fallen by 19%.

There is another simple way we can try to tell how far being excluded in itself might be leading to children committing crimes - did they commit the crime before or after they were excluded?

It is about half and half.

The Ministry of Justice says that, of the roughly 50% of children who were excluded after committing a crime, more than half were excluded within 30 days of the offence. That suggests that at least some of these children were excluded because they possessed a knife rather than the other way round.

It is not the case that any one of these risk factors will inevitably lead to a child becoming involved in crime.

About 60% of young people convicted of knife possession offences in 2015 had been eligible for free school meals, but only 1% of children eligible for free school meals were offenders.

One in five children who committed knife offences in that year had been excluded from school, but only a fraction of children who had been excluded would have committed, or gone on to commit, crimes.

- Published7 March 2019

- Published5 March 2019