Child sexual abuse: 'I sometimes wonder how I managed to survive'

- Published

How do people sexually abused as children start to repair the psychological damage done in those early years? Three victims tell how they have used creative pursuits - art, poetry and playwriting - to channel their feelings, while a doctor explains the logic behind the method.

Jemma

Jemma's house in Lancashire is full of laughter. Warm and chatty, she sits on the sofa surrounded by pieces of her colourful art, as family members come and go.

Her home is unlike the house she was taken to as a schoolgirl, where she was plied with alcohol and groomed for sex by a man eight years her senior.

"No carpets, just floorboards," she says, describing the house. "Lights were every now and then broken or smashed. Nothing in the kitchen. Empty.

"Upstairs just a bed. No sheets. And a mattress. It wasn't a home, just a house".

Jemma, who is due to start training to be a college teacher, said she has only started accepting what happened in the last three years

She was 15 when the grooming began, although she says she did not recognise it for what it was.

He was 23, and they had met through a mutual friend. He invited Jemma - and others around her age and younger - to the house, where he was joined by older men.

"In my eyes it was just an older male who was paying attention to me and I think I thrived off that," says Jemma.

"Having an older male that would buy me things - buy your fags, buy your alcohol, give me his bracelet that he claimed were really important to him."

Alcohol was shared - "drink up, drink up", he used to tell her - and soon the sex started. If Jemma resisted, he was not violent but would "throw sarky comments out there and be a bit nasty".

Jemma says things she had witnessed in the house - involving other teenage girls - "will probably stay with me for a long time".

The pair fixed up meetings, after school and late at night, using a mobile phone he had secretly given Jemma. But it all ended when Jemma's mum discovered what had been happening and the police were called.

She uses primary colours to draw people in and then likes "seeing the looks on their faces when they realise what it's about"

Jemma's abuser pleaded guilty and was jailed for five years for sexual activity with a child and child pornography charges. At the time of the court case, Jemma earned an A* in her GCSE art. Now 24, she has just finished a masters in textiles.

At university, she started working with textiles - "it was the most expressive" - and also Aboriginal art, which uses symbols to tell tales and convey warnings.

For her masters project, she decided to use symbolism to tell her story and warn others. She describes art as "like therapy".

"All my designs are bright and colourful because I wanted everyone to discuss child sexual abuse openly and it not to be a sore subject that everyone avoids," she says.

One of Jemma's pieces - a cushion covered with things her abuser used to say to her and phrases related to her experience

Jemma, who is married and a mother, says she has come to terms with what happened, although still asks the question "Why me?"

There are too many false stereotypes, she says, of what a victim of grooming looks like - someone in the care system or involved with the police. But she had a happy home life, a good support system and was doing well at school.

Ruby

Strong winds rail against the windows of Ruby's apartment block in north London as she tells her story - it's the week Storm Gareth hit the UK.

Ruby says she was first sexually assaulted aged five. By the time she was 10, she was being raped regularly. At 13 she became pregnant.

"I still feel a sense of how could this happen. How could people treat children like that?"

"It was very difficult. I didn't know exactly what sex was," says Ruby, now 62.

"He'd been doing this to me for a while, I didn't know what it meant. And then it started dawning on me, maybe it was age 11 or a sex education class, I started thinking is this the thing that can make a baby?

"And I went with my friend to the library to look up the reproductive system. There was a sort of horror as it dawned on me that this is the thing that makes a baby. So when my periods stopped, I put it together with what I read."

She saw a doctor and underwent an abortion.

The tale of her abuse is horrific. She says she felt "utterly powerless" and, looking back, thinks that she disassociated from her body when the abuse happened.

Ruby also says she writes on child abuse because of the "campaigning aspect" to helps reduce and stop child abuse by highlighting it

But the impact stretched far into her life, even years after it ended.

"Having been forced to accept the unacceptable and having lived it for so long, it sort of continues," she explains. "I was out and about on my own, very, very vulnerable. Homeless really. Sofa-surfing.

"All the violence and adrenaline and everything that went on, that's what I was used to. And I continued putting myself in a lot of danger. I really sometimes wonder how I managed to survive that."

She says she was unable to make decisions in her own interest, and was left "depleted" by her relationships with men.

Her journey to recovery has been long. Ruby says only in the past five years has she found the right type of therapy.

And, having been a bright student in school with a talent for writing, she was drawn to the written word.

"I've wanted to write this story, my story, since I was in my early 20s," she says. "I've always felt in shock about it, I'm still in shock now, 55 years later.

"And I think [child abuse] is something that needs to be brought to the attention of society, to say, 'you call yourself a civilised society? This is uncivilised.'"

In 2006, she made a start on a book - producing a 40,000-word manuscript - and later started writing poetry.

"I think in truth, how the poetry started was 'this book is taking forever, I want to do something that I can finish'," she jokes.

She now attends a monthly poetry workshop, and has had her poetry published in anthologies.

Why write? "It's the C word: cathartic. It's this outpouring. Especially as having had to suppress so much under these circumstances, it's liberating.

"And there's something about putting it down in black and white. It never completely leaves you but it lightens your load."

She adds: "Also, I do feel a campaigning aspect. I don't want to force it down anybody's throat but I do want to be part of a movement, energy, organisation that helps to reduce and stop child sexual abuse.

"And it's not going to reduce and stop so long as it's kept secret and kept quiet."

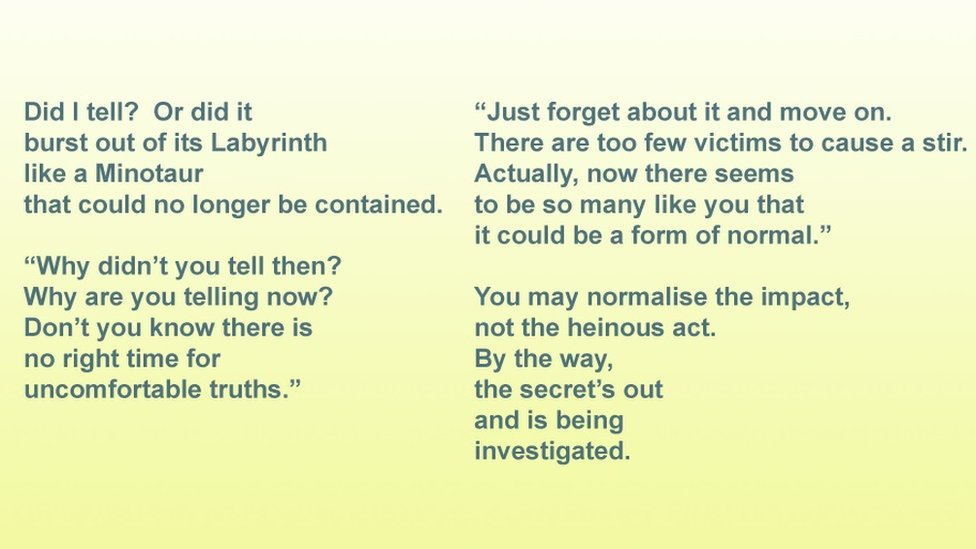

Extract from Ruby's poem, called Secret

Ruby says there is a "bitter-sweetness" with, as an adult, learning that child sexual abuse was so widespread.

"On the one hand it's awful, it's uncivilised, that it's terrible that it's widespread. But on the other hand, as a victim, you don't feel so alone."

Patrick

"One of the most moving pieces I have ever seen," was the verdict of comedian Sandi Toksvig on seeing the show Groomed.

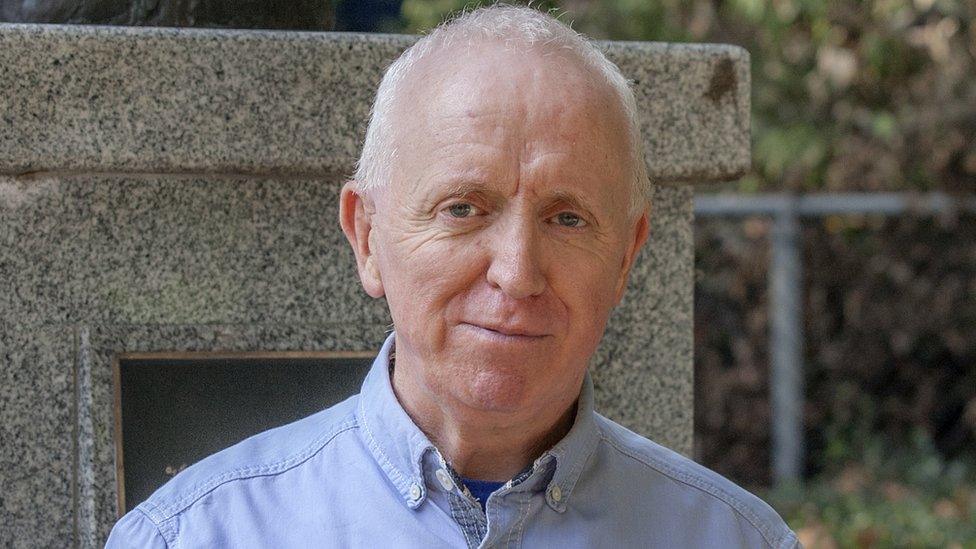

The one-man play is written and performed by theatre director Patrick Sandford. It tells his story of being sexually abused, aged nine, by a teacher in the 1960s.

"I would have to stand behind the table in front of the class and read to the class," says Patrick, now 66.

Award winning director Patrick used to be the artistic director of the Nuffield Theatre, Southampton

"While I was reading, he would hold the side of the book. With his right hand, he used to slip his hand up my leg and into my shorts and play with my genitals.

"Of course it was the most embarrassing and terrifying experience for a nine-year-old.

"He would say how clever I was and how well I was reading and how he would make me top of the class."

Patrick says when the abuse stopped - "I was thrown away for a younger model... I knew I was no longer his favourite pupil" - it was "devastating".

"It was, I think, in many ways, as catastrophic psychologically as the actual abuse. It made me feel worthless. What had I done wrong? I felt hideous and ugly."

For 15 years, Patrick did not allow anyone to touch him physically, except for a handshake or peck on a cheek.

"I was repressed completely sexually. I felt I was hideous. I had terrifying body dysmorphia. I used to carry a newspaper so that people wouldn't see my face."

His recovery started when he began working professionally in the theatre - what he calls his "survival strategy" which gave him "a reason for living".

He underwent therapy and later he started to write the play Groomed as a "therapeutic, cathartic exercise".

"Creating fiction was easier and safer than real life," says Patrick on how the world of theatre helped him

"I read it to my therapist, in a tiny little room and he said you have to do it, you have to perform it. I did it for three friends. Then I did it for my agent.

"Gradually people said I have to do it. I said I only want to do it if I can have a saxophone. I wanted no depressing music - it can be melancholy, but that's not the same thing.

"I didn't want it to be self-indulgent… it's so easy to write about misery, everybody gets challenges and misery."

It's important that ordinary abuse stories are told, says Patrick - not just those of celebrities like Jimmy Savile

Perhaps astoundingly, Patrick also performs the character of the teacher in the play.

"I didn't want it to be black and white, the man who abused me is the baddie and I was the innocent goodie. I think it's more complicated than that."

He adds: "Doing the play can be completely cathartic but it can also be quite churning. It feels like opening a wound and cleaning it out but ultimately it's very healing having these conversations.

"Suddenly my experience is being believed. It's lovely to be heard."

How can creativity help?

Dr Rebekah Eglinton is the chief psychologist to the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse and explains how creativity can help recovery.

"The one thing that is really powerful is the use of symbolism," she says. "What I mean by that, is sometimes it can be very difficult to talk directly about 'me' and about things that might feel completely overwhelming.

"But if I can tell a story through the medium of poetry, for example to talk about what has happened, I can talk about it indirectly. It means it's easier to communicate."

She adds: "It's a bit like the story of Perseus slaying Medusa. If you think of Medusa as the trauma, looking directly at the trauma can be so utterly overwhelming because the trauma is so horrific.

"But by looking indirectly [using a mirror], he's finding a way to speak the unspeakable."

But she emphasises that everyone is an individual: "Recovery and that journey from trauma into wellness - whatever that looks like for someone - is an incredibly individual journey."

With thanks to the Truth Project. You can find out more about how to share an experience with the Truth Project at: https://www.truthproject.org.uk, external, by calling the information line: 0800 917 1000 or emailing share@truthproject.org.uk.

Information and support for anyone affected by sexual abuse (current or historic)

- Published14 April 2019

- Published28 March 2019

- Published18 March 2019

- Published18 March 2019

- Published1 March 2019