Drug crime mapped

- Published

Drug crime is increasing in many small towns and villages even as it falls significantly in city centres, the BBC has found.

Police data shows drug crimes in England and Wales have fallen by more than 50,000 in the past five years.

But national averages hide a major shift in where drug crimes are being committed.

It comes as the government pledged an extra £85m to prosecutors to help deal with a rise in violent crime.

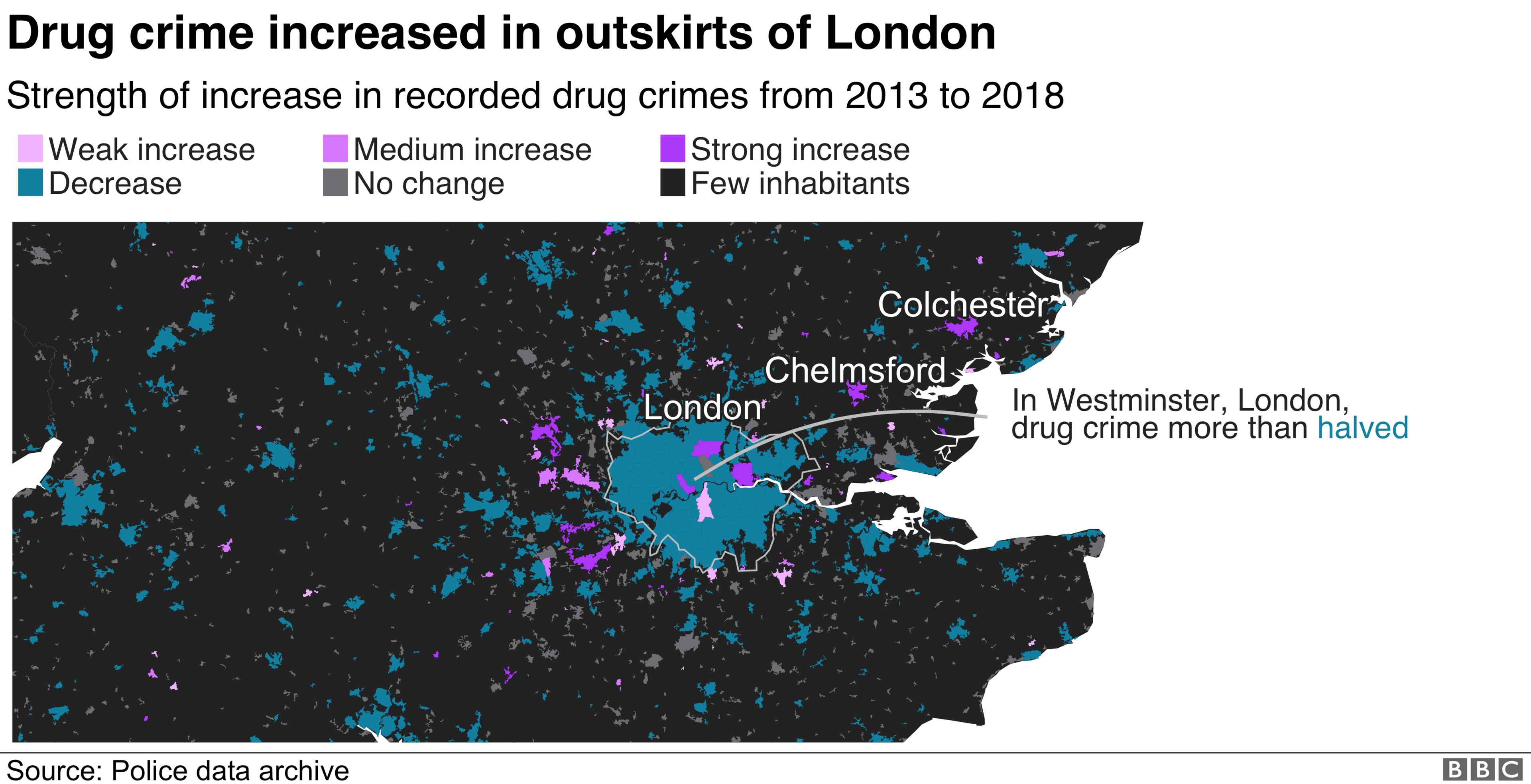

In London, 30 out of 36 areas saw either a decrease or no significant change in recorded drug crime over the past five years.

But moving outside of the capital, in the South East and East of England, there were 74 small towns and villages that bucked the trend and saw increases in drug crime.

Sorry, your browser cannot display this map

The map above used a statistical model to classify areas that have experienced a significant change in drug crime. Weight is given to areas with a strong overall trend of increasing or decreasing crime across several years. Where there is no strong overall pattern in a particular location, those areas have been labelled as having "no change". 'Drug crime' refers to drug-related incidents reported to or identified by the police that an officer classes as criminal, whether or not the crime results in a charge.

Tap here, external if you can't see the interactive map above

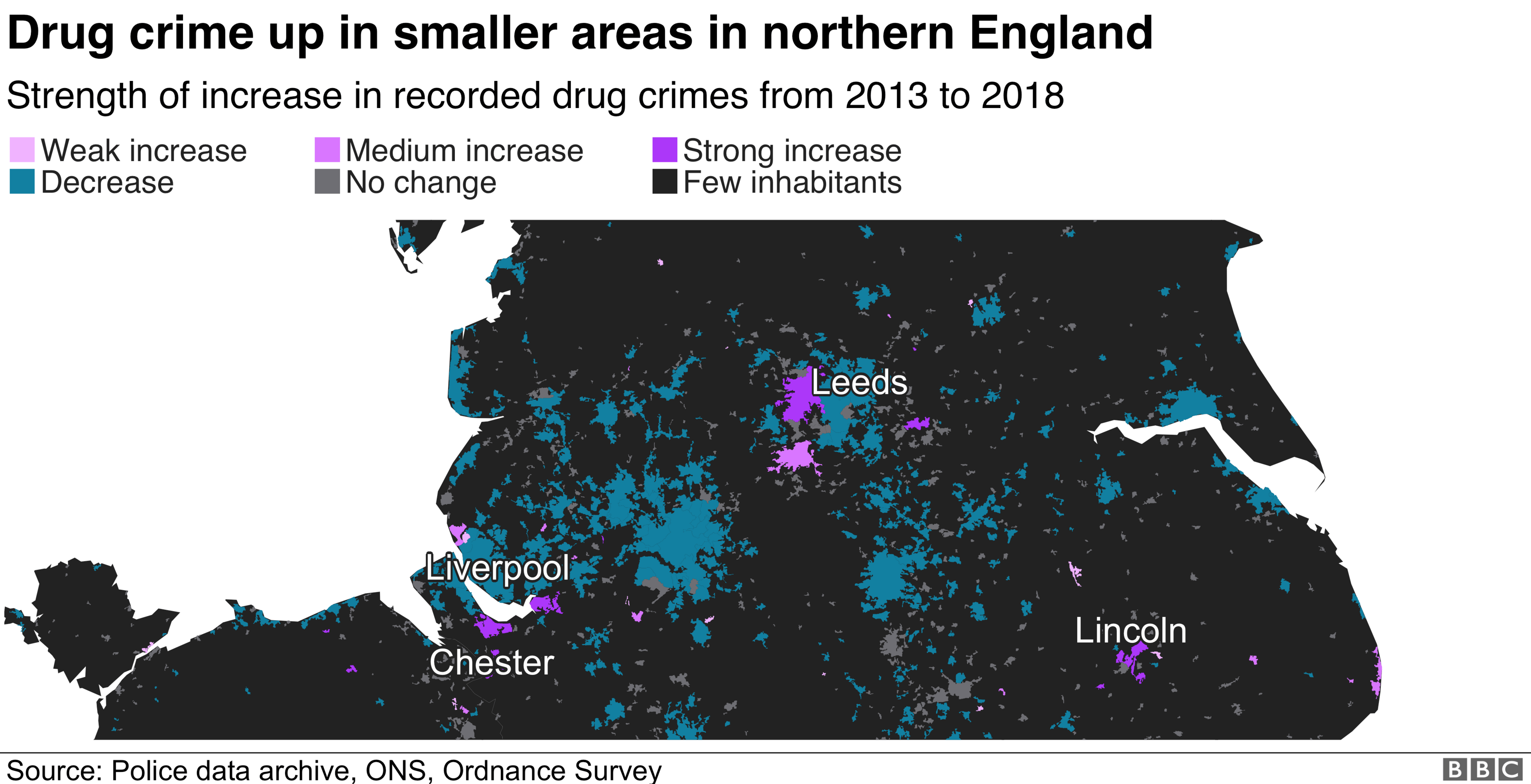

In Liverpool drug crime has fallen by nearly 20%, but 15 miles away in Chester it increased by 40%.

The push from drug gangs to find new markets within easy commuting distance of their home cities where competition for market share may be lower than in their base is sometimes called county lines.

County lines often involves the use of teenagers to ferry drugs between cities and towns, and to set up drug-dealing operations in the homes of addicts in a process known as "cuckooing".

The National Crime Agency says more and more children and young people are being referred to the "National Referral Mechanism", a system designed to identify human-trafficking victims, as a result of county lines.

"The county lines model is linked to violence and relies on the exploitation of vulnerable people to make a criminal profit, with organised crime networks bringing terror to the communities they operate in," NCA spokesman Nikki Holland said.

"We're working with partners to gather vital intelligence to help us dismantle these networks piece by piece and ultimately protect those at risk of harm."

London, the West Midlands and Liverpool are the biggest exporters of county lines drug crime, according to NCA analysis, with increasingly diverse areas targeted by the gangs, from large towns to rural communities.

The BBC counted the number of drug crimes in "built-up areas" - the villages, towns and cities where people live, according to boundaries drawn up by the Office for National Statistics - using recorded crime data from the police data archive. It then measured how much recorded crime went up or down in each area in the five years from 2013 to 2018.

However, the volume of crimes recorded can be affected by police activities and how the police focus on their different priorities.

Most of the smaller areas in the data have seen falls in recorded drug crime, defined as offences involving either the possession or supply of illegal drugs, broadly in line with the national picture of reducing drug crime overall.

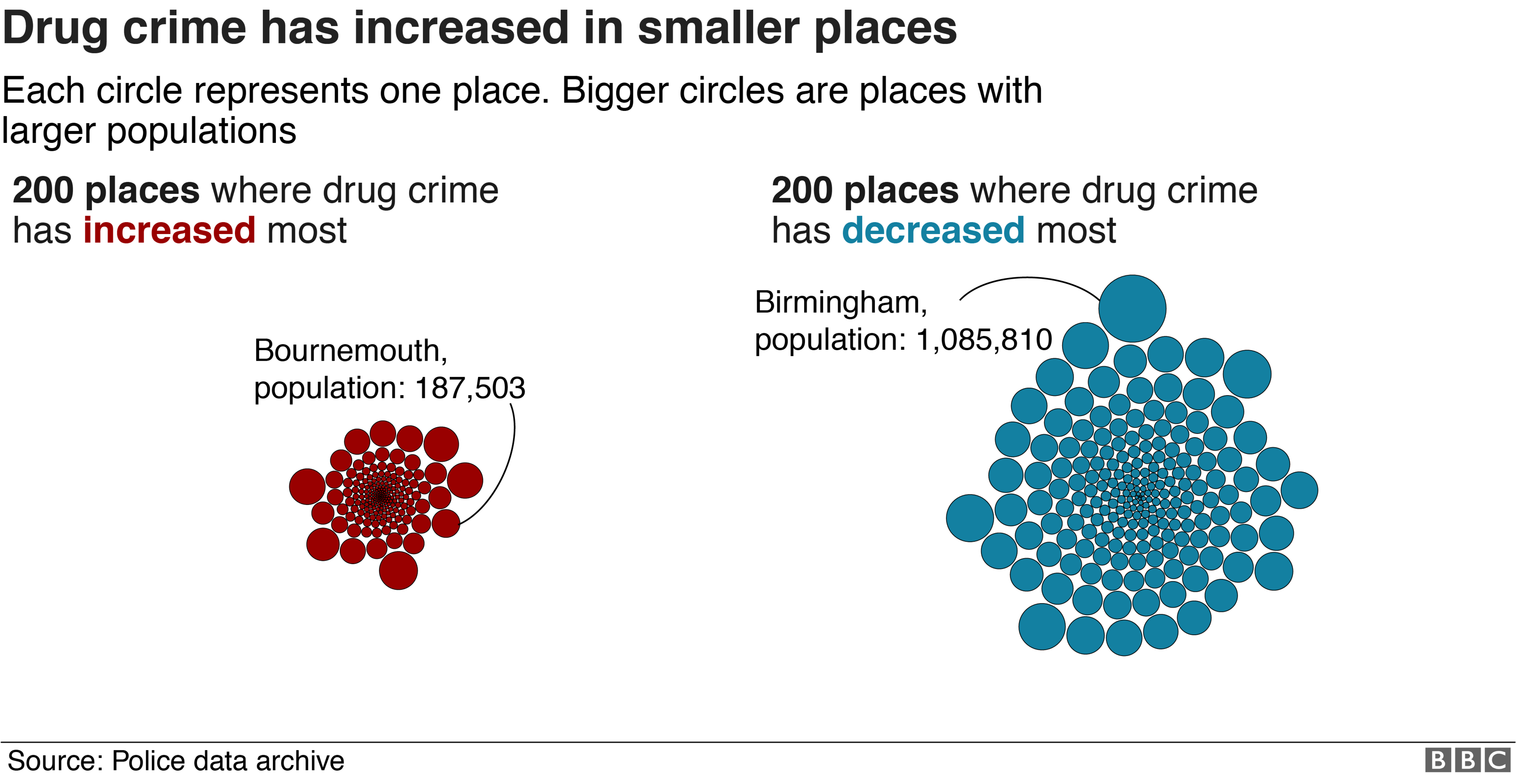

But of the 200 areas where drug crime has increased the most since 2013, almost three quarters have a population which is lower than the average for all built-up areas. In contrast, of the 200 areas where drug crime has decreased the most, nine in 10 have an above-average population.

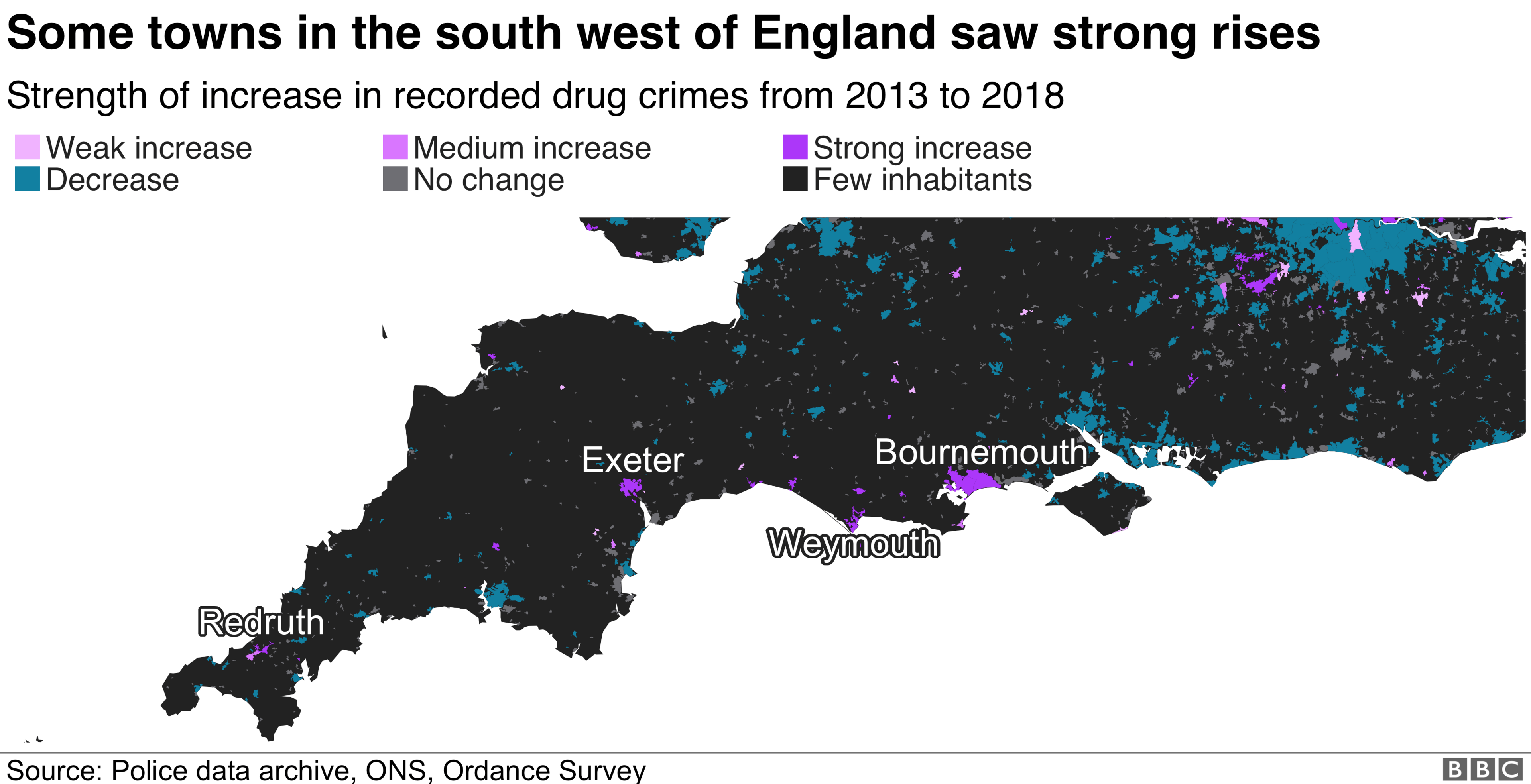

As well as towns on the peripheries of cities seeing increases, another pattern can be seen along the south coast of England. Bournemouth and Weymouth both saw rises of at least 50%, and Swanage, Bridport, Lyme Regis, Exeter and Redruth in Cornwall all saw significant increases in drug crime.

"As a society, as law enforcement, as people who work in the public sector, as the public, we all need to come together and we all need to understand that this is happening on our streets right across the country. And we need to work together, as we are, to do something about it," Assistant Chief Constable Chris Green, the head of the North-West Regional Organised Crime Unit, told the BBC.

"There are conservative estimates of 10,000 children. Ten thousand children across the United Kingdom who have been dragged into county lines.

"If you have someone who is criminally exploiting a child, a young person for the purposes of criminality, they are ruining their lives by exposing them to risk that they shouldn't be exposed to. They're dragging them into criminality, and once they're dragged into that criminality it has huge consequences for their life chances.

"Are they abusing that child? Absolutely they are. "

Correction 12 September 2019: This article originally referred to the village of Westhumble in Surrey, where figures show there's been an increase in drugs offences in the past year. Surrey police subsequently confirmed these cases were related to drugs possession in the surrounding area and on the 13 August we updated our article to reflect that. We have now removed all references to Westhumble from the article entirely. The village is not a centre for county lines dealing and we accept it should not have featured in reports about how drugs gangs are moving away from cities and into less densely populated areas.

What is County Lines?

.

- Published12 August 2019