London Bridge attack: Could it have been stopped?

- Published

The inquest into the eight victims of the London Bridge attack has ended with the coroner concluding they were unlawfully killed.

Over two months, the inquest heard detailed evidence about whether the attack could have been stopped - either by the security services or through better protection on the bridge.

The coroner criticised the lack of barriers on London Bridge - which he described as "particularly vulnerable" - but said he was "not convinced" MI5 and the police missed any opportunities to stop the attack.

So what do we know about the investigation?

MI5 knew ringleader had extremist views

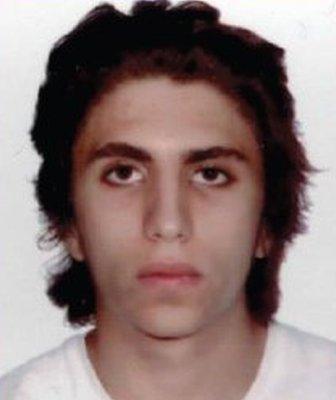

Khuram Butt

Suspicions about Khuram Butt, who led the Saturday 3 June attacks, date back to 2015.

Butt's brother-in-law called the anti-terrorism hotline to report his increasing radicalisation - but that information reached neither a police team that might have acted on it, nor MI5.

Nevertheless, MI5 already had intelligence that Butt was a supporter of the banned al-Muhajiroun network. Its information suggested he wanted to launch an attack - but he did not seem to have the ability to do so.

So the security service opened a full investigation in 2015 and investigators watched to see what Butt would do next.

Investigators never saw the whole picture

The service received other information about Butt - but didn't connect it to the man they were investigating until after the attack.

That separate information didn't fill in the blanks about what his plans were. And that was the story of the next two years.

Investigators suspected that he supported the Islamic State group. His phone was full of extremist material - like so many other suspects - but he wasn't doing anything specific to convert his aspirations into actions.

Gareth Patterson QC, representing six of the victims' families, said they were bewildered by what they believed was an "inadequate investigation".

He argued that Butt's plans would have been revealed had MI5 put more effort into his case.

But the police and security service witness, codenamed Witness L, insisted there had never been any intelligence trigger that would have made Butt a top priority.

In his closing submissions, Sir James Eadie QC, for MI5, argued that even if the service had put even more resources onto Butt, there was no evidence to prove it would have led investigators to uncovering the plan.

He argued Butt and his accomplices were careful to plan in secret and alone.

Khuram Butt while working as a customer service assistant for Transport for London

Intelligence interest was reduced

MI5 concluded in 2016 that Butt might have ultimately decided to try to go overseas to fight - probably in Syria. That placed him below the top priority suspects - but he was still the subject of some serious scrutiny.

But the lack of a clear view of Butt's intentions - and demands for MI5 resources to look into people who appeared to be planning attacks - led investigators to suspend his case between 21 March and 5 May 2017.

MI5 needed resources that had been dedicated to Butt for more urgent priorities. Before his investigation was reopened, he was also reclassified from someone who was likely to be a threat to national security, to someone who might be.

Two weeks before his attack, an assessment of whether he had the intent and capability to be a lone attacker concluded the threat he posed was "unresolved".

Butt had access to children

MI5 had received intelligence that Butt was teaching Koran classes to children - but not where.

It passed this tip to the police - who have the responsibility for preventing children being drawn into violent extremism. The security service suggested some possible locations - but they did not include the Ad Deen school where he was working alongside his fellow future attacker, Youssef Zaghba.

Lawyers for the families argue this was an opportunity missed. Had MI5 and the police established Butt's link to Zaghba - it may have led to further intelligence as to their intentions.

MI5 argued not. Zaghba would have appeared a social contact - and Butt's extremism was already known.

The attackers met at a gym

Rachid Redouane and Youssef Zaghba outside the Ummah Fitness Centre

One of Butt's haunts was the Ummah Fitness Centre in Ilford, east London. And he met both Zaghba and third attacker Rachid Redouane there.

The gym was run by Sajeel Shahid, who was previously said in court to have run a training camp in Pakistan attended by the ringleader of the 2005 London suicide attacks.

MI5's witness told the inquest there was nothing to suggest the gym was a centre of extremist activity.

Mr Patterson, for the six families, said he could not understand why the gym had not become a focus of investigation.

After the attack, it emerged that the three attackers appeared to meet outside the gym late one night and used anti-surveillance techniques to avoid being listened to while talking.

"The attack planning was there to be detected," said Mr Patterson.

There was a bureaucratic mix-up

Youssef Zaghba

The Italians had their own concerns about Youssef Zaghba after he was stopped at Bologna airport in 2016. He apparently said he was going to Turkey to be a "terrorist" - before clarifying that he meant "tourist" (the Italian words for both, as in English, are similar).

Italian authorities asked the UK if they had more information on Zaghba - but MI6, who received the memo, didn't translate it for two months and it ultimately ended up in the wrong email inbox inside MI5. It was never acted on.

MI5's witness told the inquests that it is possible that had the request been dealt with, the UK would have put Zaghba on a travel watch list - but that it was "unlikely" to have launched an active investigation into him.

The planning phase is unknown

Mr Patterson told the inquests that the planning did not begin on the day of the attack - it might have been going on for months - and that could have been detected.

He said the men would have needed time to bond and trust each other and that there were other steps to take - such as buying knives and material for the fake bombs they carried.

In his closing submissions, MI5's counsel Sir James Eadie said that even if the two other men had been identified prior to the attack, there was no evidence to show that there was missed intelligence that would have justified a major investigation into their activities.

And what about the bridge?

An emergency response helicopter landing on London Bridge

Counter-terrorism police have a secret list of what they think are the most vulnerable targets for terrorism in the UK - including which crowded places might be attacked.

The inquests heard that had the rules around how they assess those sites been applied in a less rigid way, London Bridge might have been classed as a more vulnerable target.

Two days after the attack on Westminster Bridge and Parliament in March 2017, a counter-terrorism security adviser within City of London Police concluded that London Bridge was also vulnerable because of the way it was designed and the predictable size of the crowds.

But despite a growing discussion among police and the Corporation of the City of London over what to do, no action was taken before the attack.

There are now substantial vehicle-proof barriers on the bridge.

In his conclusion, the coroner described it as "a location which was particularly vulnerable to a terrorist attack using a vehicle as a weapon".

He said without "weaknesses in systems for assessing the need for such measures on the bridge and implementing them promptly" barriers might have been installed.