Can you imagine your way to success?

- Published

"It's a constant battle within, more than what happens outside," said the Serb five-time Wimbledon champion

After Novak Djokovic won Wimbledon for the fifth time on Sunday, he credited the power of his imagination.

"I always try to imagine myself as a winner," said the champion, as he also stressed the importance of mental and emotional strength.

Of course, the mind can only get you so far - otherwise more of us would be winning the lottery or playing sell-out concerts at Wembley.

But sports psychologists say research shows the technique of "imagery" brings real results, and can "absolutely" help people in everyday life.

"It's one of these untapped skills that almost every human being can use," says Dr Jennifer Cumming, an expert on the technique from the University of Birmingham.

She says there has been "tons of research" on the power of imagery in normal life. "Generally we can all capitalise on this and the more we use it, the more we can improve it."

Imagery is not just useful in sport, says Dr Cumming - it can help prepare for situations where you may feel under pressure

Essentially, the technique of "imagery" involves creating or recreating an experience in your mind.

It is one of the core techniques used by athletes in sports psychology.

"There's a large body of evidence that shows more successful athletes are more likely to use it and more likely to have used it when they are quite young," says Dr Cumming.

'Smell the freshly-cut grass'

Sports psychologist Dr Josephine Perry, who uses imagery in her work with athletes from a range of disciplines, says it can sometimes "feel a bit silly" - but those who take it seriously will really benefit.

"The research shows the more realistic you are able to make it, the more it works," she says. "It is about being able to incite the smells, the senses."

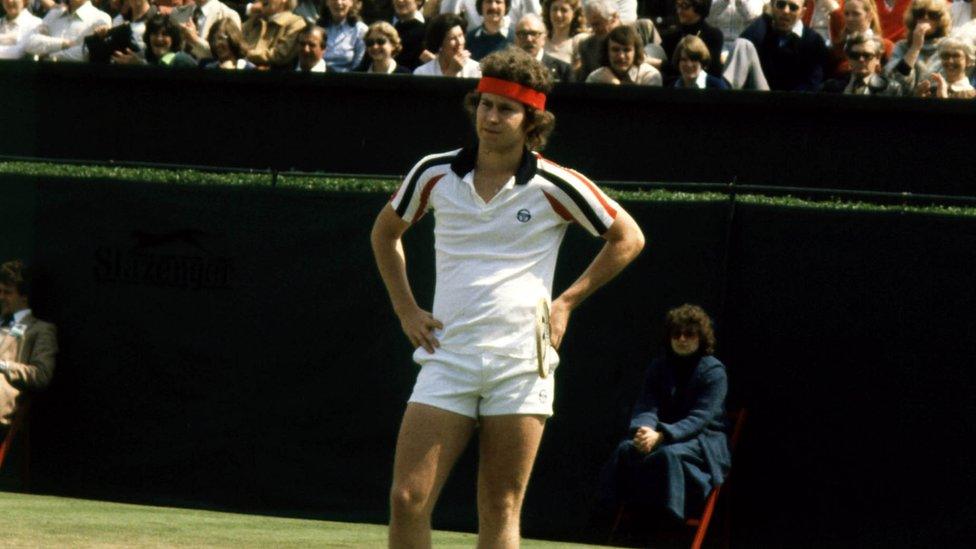

She gives the example of a tennis player who might often lose their temper on court, throwing their tennis racket down.

"We would work on when you feel that trigger, the hot button. And we start to write an 'ideal scenario'.

"For example: 'Usually this would set me off doing XYZ, but in this scenario what I want to do is take a deep breath.'"

John McEnroe, seen here contesting an umpire's decision in Wimbledon in 1979, was famous for his outbursts

Dr Perry creates a "script" with the sports player - often in real time - about how they want to behave in that situation, before recording it on their phone and listening back to it regularly.

"We want this to be as realistic as possible," says Dr Perry. "Write what you see, hear, feel, taste, smell.

"If you're on a golf course, you can smell the freshly-cut grass. You can see the flag at the end."

Dr Perry says she has also used the technique with marathon runners, to prepare them for the 18-22 mile point where they may be struggling and low on energy.

"We'd get the athlete to watch stuff on YouTube on that specific point. We'd go through a map and look at what was on the right, on either side."

She says the runner's script would read something like: "I have run under the banner, to my left I can see a set of toilets, to my right is the water filling station. My friend is at mile 19."

One of her clients, a trampolinist, created a script of their whole routine - even adding in the sound of the cheers. Another, an ultra-runner, was scared of going downhill so they worked on imagining the process together.

Imagery is useful, adds Dr Perry, because there is no real-life practice for eventualities such as losing your temper or endurance runs, where you must limit training for fear of injury.

She also used the technique with medical students preparing for practical exams.

Imagining can help with weight loss, one study found

"They knew all their stuff," she says. "The nerves on the day stop them knowing what's in their gut, and make them question everything... Imagery is really good for something like that, you can get through a situation with confidence."

And a study last year from the University of Plymouth, external also found mental imagery helped overweight people who were trying to lose weight.

"Not just 'imagine how good it would be to lose weight' but, for example, 'what would losing weight enable you to do that you can't do now?" said Dr Linda Solbrig who led the research. "What would that look/sound/smell like?', and encourage them to use all of their senses."

Imagery 'primes' brain

According to Dr Cumming, the evidence shows that the benefits of combining imagery with regular physical practice is two-fold: not only will athletes perform better but they will also have psychological advantages, such as being more focused and confident.

"What we think happens is that when you image, similar areas in the brain are active which are involved in motor skills," she says.

"If you were imagining kicking a ball, the areas of the brain associated with foot movement would be more active."

It effectively "primes" your brain, giving it "extra opportunity to practise".

Many people may already use some level of imagery, Dr Cumming adds. When you lose your keys and you backtrack through your steps - that's imagery.

"It is any time you experience anything in your mind's eye," she says. "People use it pretty much any time where you need to prepare for something where you might be under pressure".

Whether it is asking your boss for a pay rise or preparing for a presentation, she says imagining the situation in multi-sensory detail can be useful.

And she also adds that people often use it before something like going to the gym: visualising putting their gym kit on can help with motivation.

Johanna Konta's sports psychologist says they are in contact virtually every day

Dr Cumming says the very best athletes, such as Djokovic, will use imagery in a "very refined... strategic way" and in a variety of settings, on and off the court, at home, before they fall asleep.

She adds: "The best imagers are like watching yourself on HD television. They can feel their muscles activating, feel the touch of the tennis racquet, feel their heart beating, their emotions, their sense of excitement of confidence."

In a 2017 academic paper, external on psychological imagery in sport, researchers called it "undeniable" that imagery was a "powerful psychological technique".

But, they added: "Less is known about the potential negative consequences of imagery", even suggesting there might be a "dark side to imagery".

It cited one study which showed imagery to have a negative effect on golf putting performance under certain conditions.

- Attribution

- Published10 July 2019

- Attribution

- Published14 July 2019