Five ways UK farmers are tackling climate change

- Published

Farmers are on the front line of climate change - vulnerable to changes in temperature and rainfall, as well as increasingly frequent extreme weather events.

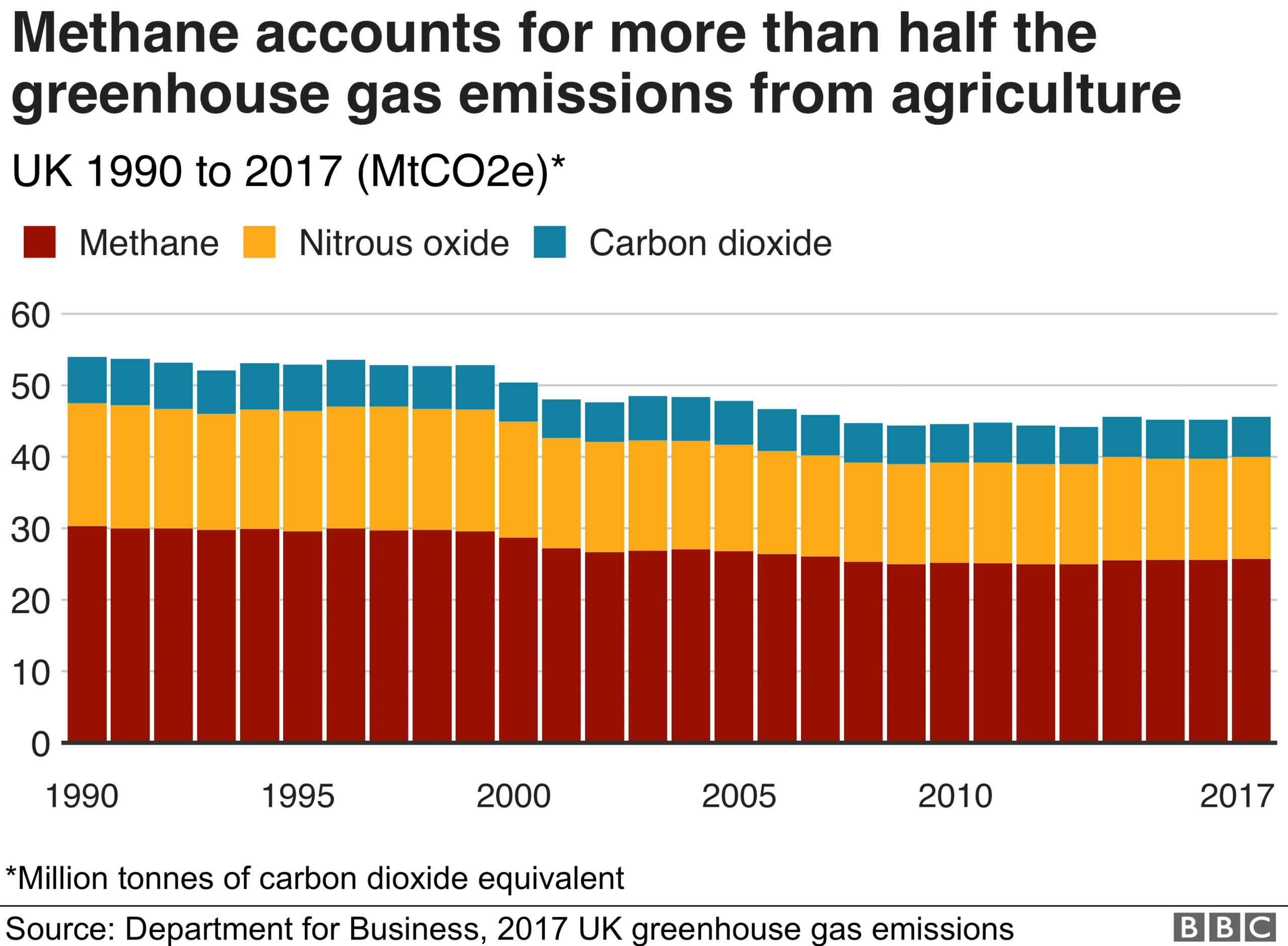

They also face criticism, in particular over greenhouse gas emissions from the meat and dairy industry, with calls for a move to a more plant-based diet.

Agriculture is currently responsible for about 9% of the UK's greenhouse gas emissions, mostly from methane.

The National Farmers' Union (NFU), which represents 55,000 UK farmers, has set a target of net-zero emissions in British farming by 2040.

That is not enough for some environmentalists, who say a comprehensive overhaul of farming practices and a move to less intensive production is long overdue.

But some new and surprising changes are happening on the UK's farms.

1. Sending in robots

Scientists in Wiltshire are part of a growing group of experts around the world developing small battery-powered robots that could drastically cut tractor use.

Tractors use diesel, a major source of carbon emissions in farming.

"Using robots cuts the energy used in cultivation by about 90%," says Sarra Mander of the Salisbury-based Small Robot Company.

The machines rely on artificial intelligence to sow seeds, identify individual weeds, and apply exactly the right amounts of pesticide and fertiliser in the right places, rather than spraying it across a whole field.

"If you had a few weeds in your garden, you wouldn't spray the whole garden, you'd just spray the area with the problem. That's what we do. It's all about precision," adds Sarra.

Sowing is done by placing individual seeds in the ground, without ploughing. Less soil disturbance means more carbon stays locked in the soil.

Robots are still relatively unusual in UK arable farming but machines are being developed all over the world to handle everything from mapping to planting, pruning and picking.

The investment bank Goldman Sachs is among those predicting a huge global shift, external to technology-driven "precision farming" in the coming years.

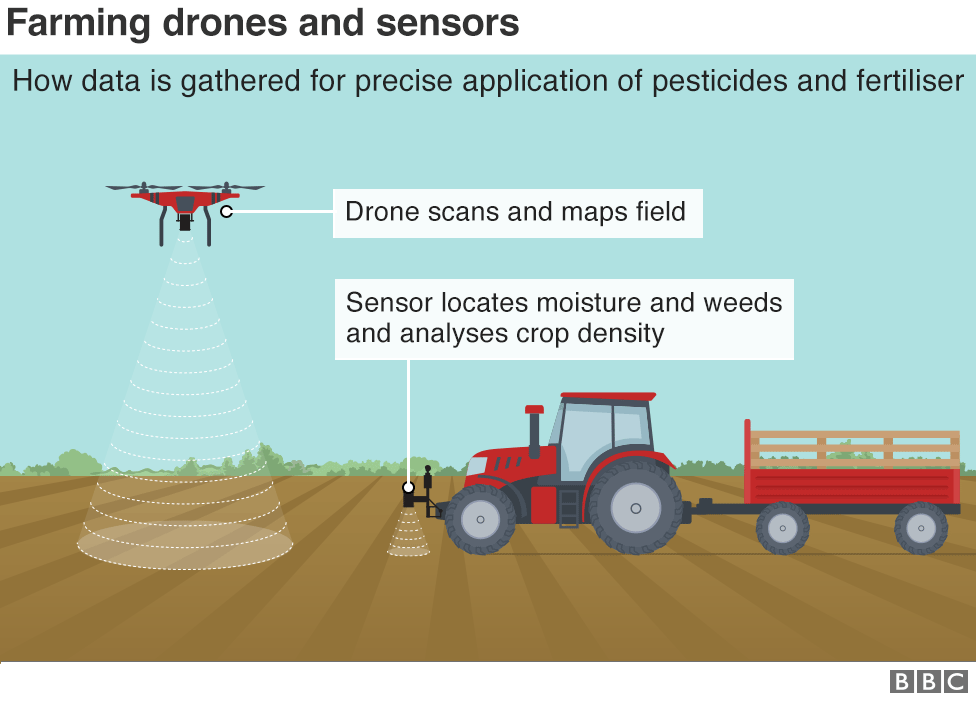

2. Using drones to map fields

Drones and tractor-mounted sensors are also being used to help farmers work out the exact patterns of moisture, weeds and pests.

The data is fed to precision machinery to target areas that need work - and leave the rest undisturbed.

Nitrogen fertiliser takes a lot of energy to produce and, particularly if it is applied at the wrong time and in the wrong quantities, bacteria act on it to make nitrous oxide.

Nitrous oxide is 200 to 300 times more effective in trapping heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide.

Mapping and analysing each field enables farmers to target nitrogen fertiliser in only those places where it is needed, at the right time - and cut their emissions.

"This kind of innovation is fantastic for us," says Becky Willson, of the Farm Carbon Cutting Toolkit, external organisation. "It's not a total answer but it can really help."

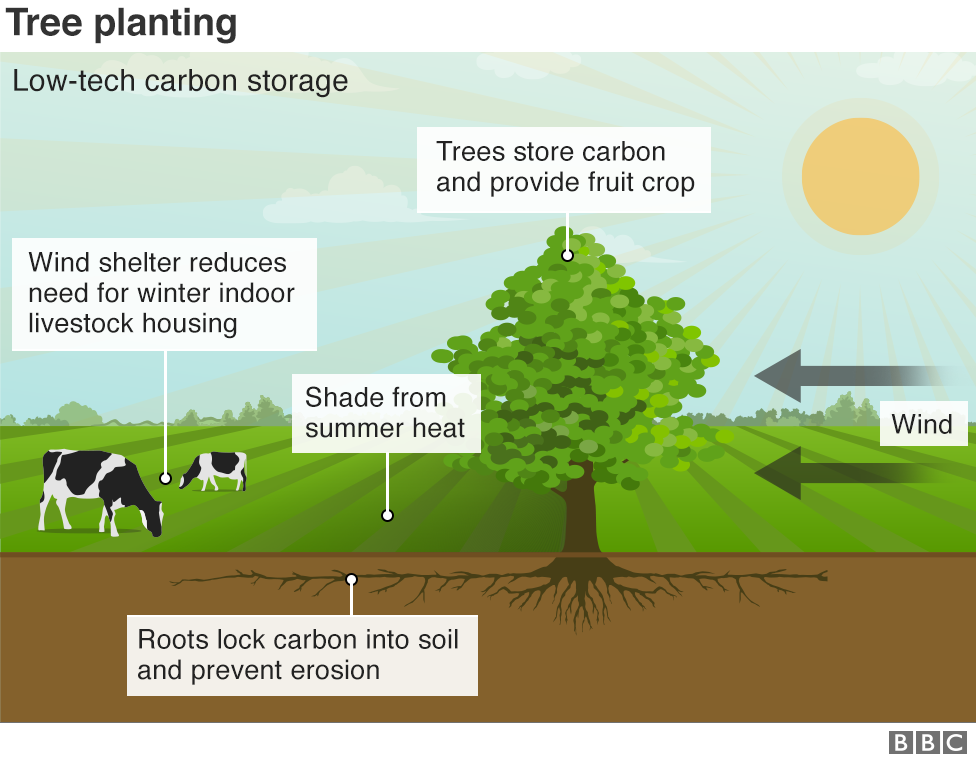

3. Planting more trees

Like Becky, many environmental campaigners also believe applying new technology without fundamental change to intensive farming practices is not enough.

Nick Rau, of Friends of the Earth, says: "New technology is helpful - but simple, low-tech solutions, looking at whole farms over a number of seasons have been grossly neglected."

Nick believes there's huge potential in a range of solutions and points, in particular, to tree planting.

Friends of the Earth is calling for a doubling of tree cover - to boost carbon storage, help with flooding and prevent soil erosion.

Cambridgeshire farmer Stephen Briggs agrees. "It's about taking lessons from nature," he says.

He now grows 13 different varieties of apples over 125 acres (0.5 sq km), about 8% of his farm.

The apple trees stop soil erosion, lock carbon into the ground, support biodiversity and deliver a new crop.

His profitability, Stephen says, has improved since he made the change, 10 years ago.

"By growing trees alongside wheat, you expand the productive space up into the air and down into the soil, plus you extend the period of the year that you're capturing the sunshine," he says.

Wind protection from trees can also reduce the time livestock need to be kept indoors in the winter, again saving on energy and cutting emissions.

4. Keeping livestock outside for longer

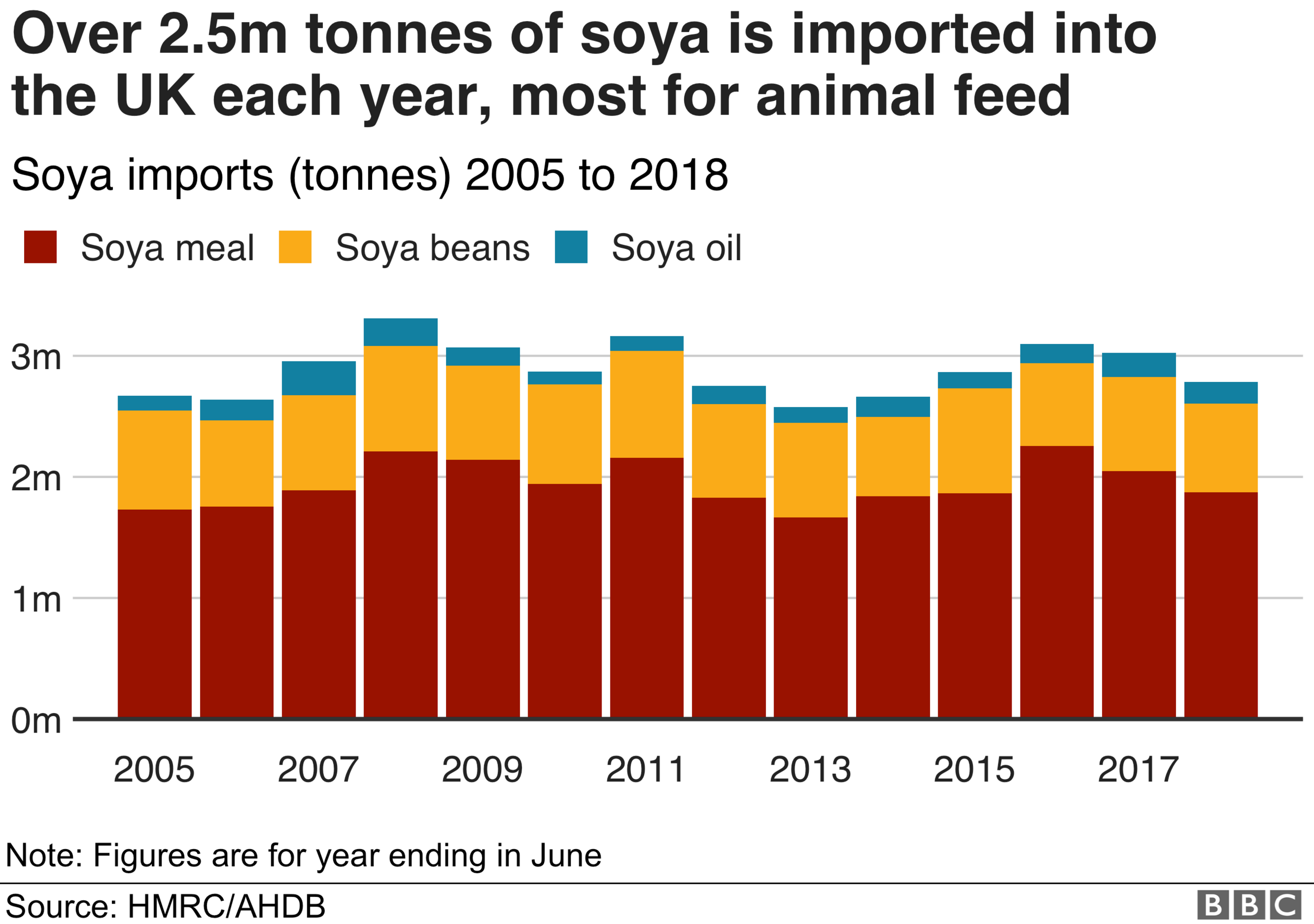

Farmers who keep their animals outdoors for longer in the UK can help to cut emissions thousands of miles away.

When animals are taken indoors, they are sometimes fed on soya imported from Latin America.

Soya is often cultivated on land that was previously rainforest, so the demand for animal feed in the UK is, critics say, exporting deforestation.

British cows are fed on grass for more of the year than cows in many other countries, so the UK's impact on deforestation through soy imports may be relatively small.

But soya production for the global animal feed industry is one of the most important drivers of deforestation, according to the Global Forest Atlas, external, and the Amazon has been cleared at an alarming rate.

It's estimated that since 1970 about 20% of the Amazon has been lost.

The environmental group Greenpeace, external has also highlighted the huge areas of rainforest lost to soya cultivation.

And Richard Finlay, of the NFU, says British farmers understand their part in fighting climate change does not end at UK shores.

"A large proportion of the supply chain has already committed to solely using sustainable, responsibly sourced soya," he says.

5. Cutting methane emissions

Cows and sheep produce methane in their digestive systems.

Methane produces 21 times as much warming in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

Whilst carbon dioxide is the biggest concern for many other industries, in farming methane is a major worry.

The NFU points to many farmers using methane from manures and slurries to generate electricity and says the British livestock industry is one of the most efficient and sustainable in the world.

But the methane problem has generated a whole range of other approaches.

"There's a lot of thinking about feed additives which might reduce methane production in the animals' guts," Becky Willson says.

Some researchers and organisations, such as Becky's, are also pointing to better breeding and genetics as a way forward.

For beef cattle, one approach in Scotland, external has been to select animals for breeding on the basis of how much methane they produce in their digestive systems.

For dairy cattle, which start producing milk at the age of two, an approach in the US, external has been aimed at lengthening the animals' productive lifespan - so the proportion of the animals' life that is unproductive and spent consuming energy and emitting methane is reduced.

Put simply, breeding cows which produce milk for longer, reduces the need for dairy calf replacements - which will consume energy and emit methane, without producing milk, for the first two years of their lives.

For lambs, with a typical lifespan of about six to eight months, the goal has been to produce animals that fatten more quickly and can be slaughtered earlier.

Research in Wales, external pointed to reductions of about six days in the time taken to fatten hill lambs, though some farmers report, external reductions of up to 30 days.

It is, quite literally, a matter of life and death.

Produced by David Brown and Mark Bryson. Read more on the BBC's Focus on Farming here.

- Published14 January 2020

- Published27 November 2023