Extinction Rebellion protests continue in London despite ban

- Published

Extinction Rebellion is calling on the government to explain its plan to meet a net-zero emissions target

Extinction Rebellion activists are continuing protests despite a London-wide ban by police.

The group says it has taken initial steps towards a judicial review of the ban. Lawyers and politicians have also criticised the move.

Meanwhile, climate change protesters targeted the Department for Transport and MI5 on Tuesday morning.

A government spokeswoman said protests "should not disrupt people's day-to-day lives".

Extinction Rebellion's co-founder, Gail Bradbrook, was arrested after climbing on to the entrance of the Department for Transport on Tuesday morning. Police also cleared further protesters from outside the building.

Activists have also been arrested on Millbank outside MI5's headquarters, where a small group had gathered. Two men briefly sat in the middle of the road before being moved by officers.

The Metropolitan Police began clearing protesters from Trafalgar Square on Monday evening following the announcement of new restrictions under Section 14 of the Public Order Act, which required activists to stop their protests in central London by 21:00 BST or risk arrest., external

The force said it decided to impose the rules after "continued breaches" of conditions which limited the demonstrations to Trafalgar Square.

Protesters who camped out in Trafalgar Square have now been moved on

Extinction Rebellion said it had taken the "first steps" towards a judicial review of the Met's "disproportionate and unprecedented attempt to curtail peaceful protest".

"Our lawyers have delivered a 'Letter before Action' to the Met and asked for an immediate response," a statement read.

Tobias Garnett, a human rights lawyer working for the movement, said the letter warned police to withdraw the order, giving them a deadline of 14:30 BST to respond, or else the group would file a claim in the High Court.

"We will be looking for an expedited hearing either today or tomorrow morning," he added.

There was a large police presence at the Department for Transport

The Met confirmed it had received "pre-action judicial review correspondence" alleging Human Rights Act breaches.

"The letter will be reviewed by the Met's Directorate of Legal Services, and we will respond to the claimant in due course," a statement read, adding it would be "inappropriate" to comment further.

Mayor of London Sadiq Khan has said he is "seeking further information" about the decision to impose the ban and why it was necessary.

"I believe the right to peaceful and lawful protest must always be upheld," he said.

'Our generation is partly responsible'

By Francesca Gillett, BBC News

"This is a rebellion, our house is on fire," sang crowds of pensioners to the tune of Elvis Presley's Hound Dog as they stood outside the gates of Buckingham Palace.

Earlier they gathered on the steps of the Queen Victoria Memorial opposite, singing songs led by two musicians, as police stood nearby in small groups.

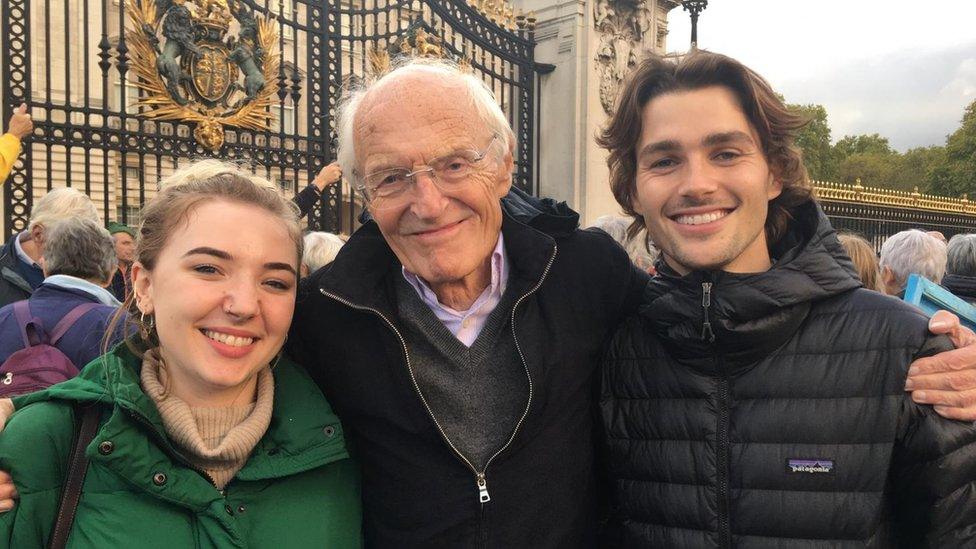

Among those here is the playwright and novelist Michael Frayn, 86, who says he was "brought in" to the Extinction Rebellion cause by his grandchildren.

Michael Frayn, 86, with his grandchildren outside Buckingham Palace

Another family of campaigners travelled over from a mountain town in Mexico, where they live, to take part in the ongoing protests.

Harmeet Kaur, 42, said she and her family had seen the footage from London and wanted to join her mother, based in Hounslow.

Harmeet Kaur, back centre, with her mum and two children

While for some, this wave of Extinction Rebellion protests is the first time they have ever attended a rally, others are veterans.

"It's our generation that is partly responsible," says retired professor Peter Cole, 75, who also took part in the civil rights movement in the US in the 1960s.

A spokeswoman for the government said the UK was "already taking world-leading action to combat climate change".

The statement added: "While we share people's concerns about global warming, and respect the right to peaceful protest, it should not disrupt people's day-to-day lives."

Home Secretary Priti Patel tweeted that "supporting our [police] is vital" and accused the Labour Party of supporting "law breakers".

'Overreach of powers'

Meanwhile, lawyers have also questioned whether the ban by police is legal.

Anti-Brexit barrister Jo Maugham QC said the move was "a huge overreach" of police powers, while human rights lawyer Adam Wagner described it as "draconian and extremely heavy-handed".

Mr Wagner added in a tweet: "We have a right to free speech under article 10 and to free assembly under article 11 of the (annex to the) Human Rights Act. These can only be interfered with if the interference is lawful and proportionate. I think the police may have gone too far here."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Shadow home secretary Diane Abbott tweeted: "This ban is completely contrary to Britain's long-held traditions of policing by consent, freedom of speech, and the right to protest."

Allan Hogarth, of Amnesty International, issued a statement saying the ban was "an unlawful restriction on the rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly".

A number of demonstrations have been staged across the capital by Extinction Rebellion, which is calling on the government to do more to tackle climate change.

Police remove an Extinction Rebellion protester from Trafalgar Square in central London

Protesters gathered their belongings as police removed the last of the Extinction Rebellion demonstration

On Tuesday afternoon, the Met said there had been 1,489 arrests in connection with the nine days of protests in London.

It also said 92 people had been charged with offences including failing to comply with a condition imposed under Section 14 of the Public Order Act, criminal damage, and obstruction of a highway.

Earlier, Parliament Square was closed in both directions due to the protest, but Transport for London said the roads were cleared by 17:30 BST.

One protester climbed on top of the railings outside the Houses of Parliament

Last week, the Home Office confirmed to BBC News that it was reviewing police powers around protests in response to recent demonstrations.

What are the rules around protests?

Police have the powers to ban a protest under the Public Order Act 1986, external, if a senior officer has reasonable belief that it may cause "serious disruption to the life of the community".

Police are also under a duty to balance the task of keeping the streets open with the right freedom of assembly under the Article 11 of the Human Rights Act 1998 , externaland freedom of expression, under Article 10. These rights are not absolute - the state can curtail them.

However, the BBC's home affairs correspondent Dominic Casciani said: "The test, if and when it gets to a human rights court battle, is whether police action was proportionate to the threat and only what was strictly necessary."

By law, the organiser of a public march must tell the police certain information in writing six days in advance.

Police have the power to limit or change the route of the march or set other conditions.

A Section 14 notice issued under the Public Order Act allows police to impose conditions on a static protest and individuals who fail to comply with these can be arrested.

- Published15 October 2019

- Published14 April 2022

- Published11 October 2019