Grenfell: Seven key points from the report

- Published

The report of the first phase of the Grenfell Tower fire reveals how the fire began, spread and became a disaster. These are some of the key findings which will influence the deeper investigation of the inquiry's second phase - into how it could happen in the first place.

There was swift action by the resident of the flat where it began

The first 999 call came from Behailu Kebede at 00:54 BST, who lived in Flat 16. His smoke alarm woke him up and he saw what was in all probability an electrical fire at the back of his fridge freezer. He called for help, alerted neighbours and waited for the London Fire Brigade to arrive.

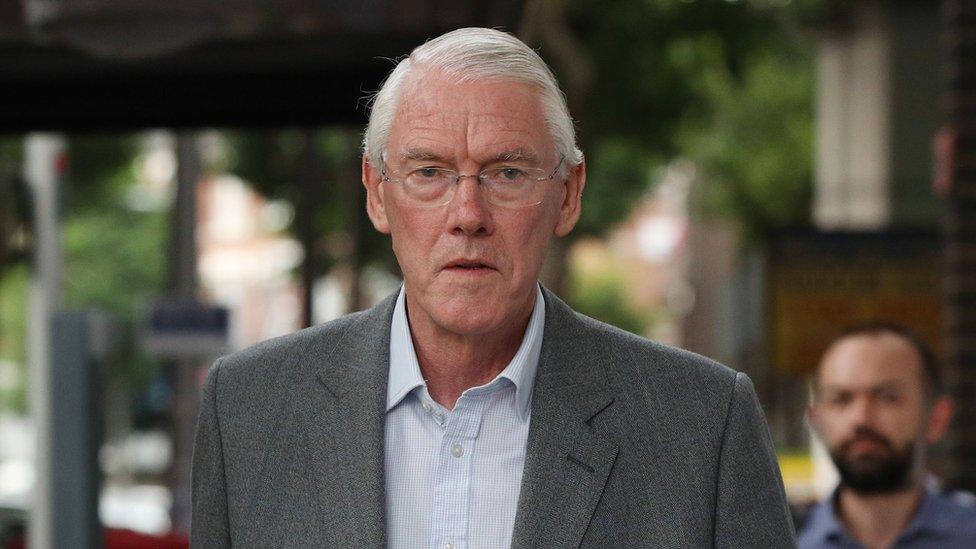

Sir Martin Moore-Bick's report found Mr Kebede blameless. He turned off his electricity and closed the flat door to keep others safe.

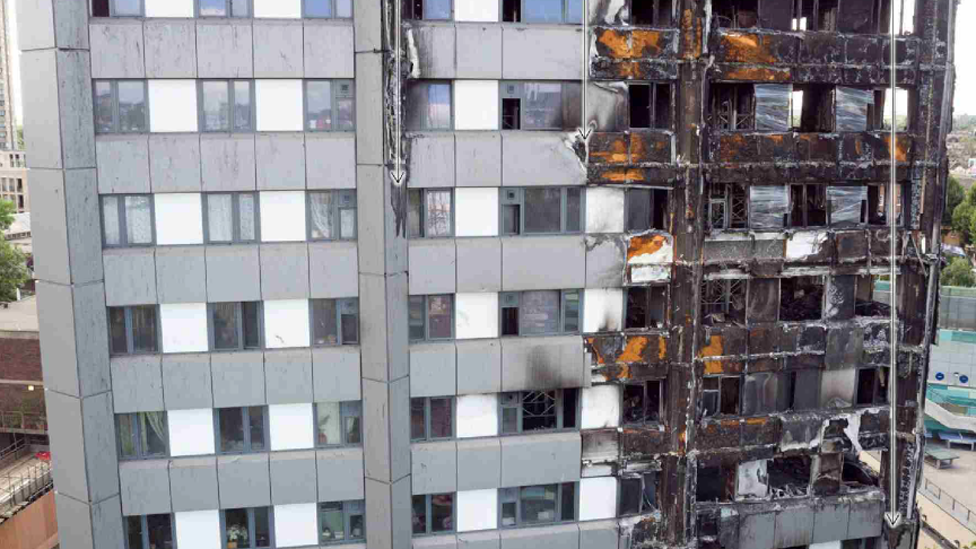

In normal circumstances that would have been enough because Grenfell's original solid concrete structure meant each flat was "compartmented" - meaning a minimal chance of a fire spreading.

Sir Martin Moore-Bick, inquiry chairman, said the resident who raised the alarm was blameless

But his efforts were in vain because of how the building had been refurbished on the outside.

The first firefighters into the flat realised something was wrong

Crew manager Charles Batterbee and firefighter Daniel Brown entered Flat 16 at 01:14 BST. They blasted the fire with a jet of water and then saw the fire had already spread from the kitchen to the outside.

This is the first evidence that Grenfell's refurbishment was contributing to the unfolding disaster. Hot material deformed the uPVC window and that created a cavity through which hot gases escaped.

They blasted water at the cladding flames to no avail. The polyethylene material in the rain-proof cladding panels was melting and burning.

"It then became clear that the fire was going up the building," said Mr Brown.

"I remember the intensity of the flame - what I can only describe as huge balls of flame falling down along with debris. It didn't stop, we kept hitting it but again, it was having no bearing on the fire."

The significance of calls from some residents was missed

Sir Martin is in no doubt that Grenfell Tower's refurbished exterior walls were not compliant with building regulations "because they did not adequately resist the spread of fire over them. On the contrary they promoted it."

Once the fire escaped from Flat 16, the flammable nature of the cladding panels allowed it to spread to the top storey in less than half an hour - but also around the sides.

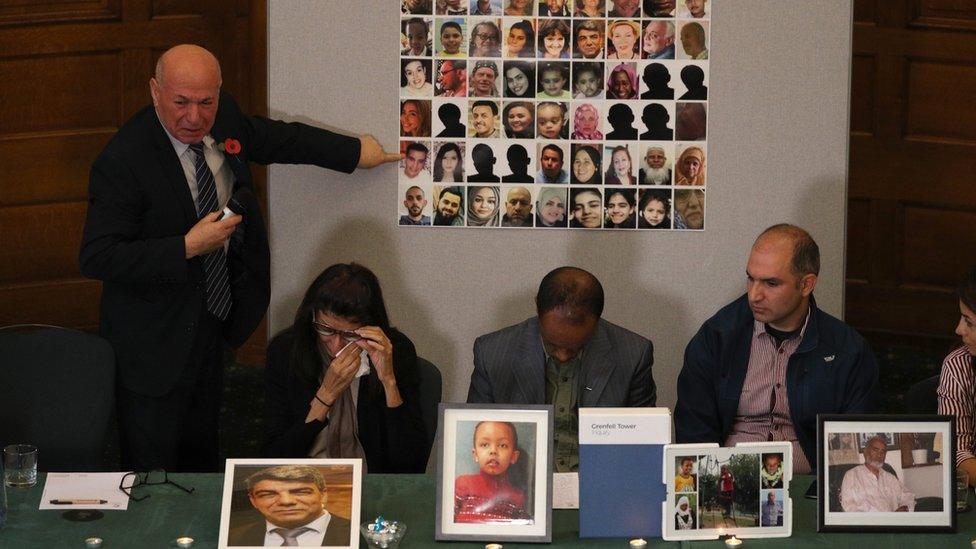

Residents warned that the fire was spreading but the significance of their calls was missed

The fire reached the "crown" of the building at 01:27 BST and the top cladding spread flames horizontally and eventually back down.

And that's why the 999 call three minutes later from Mariem Elghwahry, who lived on Floor 22, is important. She was the first to report fire penetrating her flat.

Within half an hour of firefighters' arrival, there was evidence that Grenfell's compartmentation was failing.

Control room staff couldn't cope with the calls

When a fire service receives multiple emergency calls from the same incident, control room operators tend to class the additional ones as "Fire Survival Guidance" calls (FSG) in which they give the individual information about the fire and what they need to do to stay safe.

The report makes clear that the control room supervisors appeared not to have received any specific training to manage the volume of calls in relation to Grenfell.

Operations manager Alexandra Norman told the inquiry that staff would normally stay on the phone to FSG callers until they were safe - but they were overwhelmed.

Sir Martin said: "When the flow of FSG calls became a flood around 01:30 to 01:40 OM Norman should have stood back and decided how to manage the collation and transmission of FSG information to [teams on the ground] in a way that ensured that clear lines of communication were established.

"OM Norman failed to ensure that [call handlers] obtained from callers all the information required."

And teams on the ground struggled too

Watch manager Michael Dowden - among the first at the scene - had received no training on how the materials used to refurbish Grenfell Tower would behave in a fire.

Sir Martin said Mr Dowden, who broke down in tears at the inquiry, could not be blamed for not knowing how to respond to what he was witnessing.

A second phase of the inquiry will examine how the disaster could have occurred

Mr Dowden lacked critical information from the control room - that meant that he was doubly blinded to what was unfolding.

In short, said the chairman, a relatively junior officer "had little or no support from more senior officers" and was let down by institutional failings.

He went on: "The behaviour of the fire was outside his experience and nothing he had done appeared to be having any effect. He was at a loss to understand what was happening or to know how to respond."

Nobody had an overall full understanding of how to prioritise rescues

Jessica Urbano Ramirez was described as 'loving, kind-hearted and caring'.

This is illustrated by the death of 12-year-old of Jessica Urbano Ramirez. No information from her 999 call at 01:29 BST made it to the crews. A team only went to her home on floor 20 after receiving information from Jessica's sister. By this time, she had fled three stories higher with 10 others.

In the meantime, control room officer (CRO) Sarah Russell stayed on the phone to Jessica for 55 minutes. It was clear she was in terrible danger. Jessica stopped responding but CRO Russell could still hear the sound of breathing for some time. She only ended the call when the line went silent

Jessica's call for help was the first FSG call that CRO Russell had taken. In her witness statement, she told the inquiry: "Reflecting on that call, I felt completely helpless." Sir Martin praised her courage and calm professionalism amid the traumatic circumstances of trying to help a 12-year-old survive.

The 'stay put' strategy should have been abandoned sooner

Sir Martin says in the report that LFB failed to revoke the "stay put" advice at a time when the stairs remained passable. Had it done so, "more lives could have been saved".

"The evidence taken as a whole strongly suggests that the "stay put" concept had become an article of faith within the LFB so powerful that to depart from it was to all intents and purposes unthinkable," he wrote.

"The fact that the commissioner [Dany Cotton] was compelled to ask the rhetorical question: 'It's all very well saying, get everybody out, but then how do you get them all out?' emphasises that the LFB had never itself sought to answer that question in its preparations and training and had not equipped itself to carry out a total evacuation of such a building.

"Quite apart from its remarkable insensitivity to the families of the deceased and to those who had escaped from their burning homes with their lives, the commissioner's evidence that she would not change anything about the response of the LFB on the night, even with the benefit of hindsight, only serves to demonstrate that the LFB is an institution at risk of not learning the lessons of the Grenfell Tower fire."

- Published30 October 2019

- Published29 October 2019

- Published29 October 2019