Staunch Book Prize: Should writers ditch female victims?

- Published

From the escapades of an intern-turned-spy in Turkey's capital to the tale of a priest in 15th Century Somerset, there might not be an obvious connection between the novels shortlisted for this year's Staunch Book Prize., external

But they have one thing in common: none of them involve physical or sexual violence towards women.

The prize, which is in its second year, recognises thrillers in which "no woman is beaten, stalked, sexually exploited, raped or murdered".

But while some commend it for challenging stereotypes, others accuse it of ignoring social realities.

Speaking to the BBC, shortlisted authors and other writers share their views on why female characters are so often the victims of violence - and whether that needs to change.

'Clichéd stereotypes'

August Thomas, one of the shortlisted authors, says she set out to create a "powerful three-dimensional female character" in Liar's Candle, a spy thriller about a 21-year-old intern in a US embassy who goes on the run.

"It's not limiting at all - it's really exciting to have an opportunity to tell stories where you have protagonists and villains who are powerful women," the US writer says, adding that she would find it more restrictive to rely on "clichéd stereotypes" where women are the victims.

"There can be amazing stories that do that, but I always think of putting more items on the menu - adding the vegetarian option doesn't mean you take the other stuff away."

Young women are rarely the main protagonist in spy thrillers, she adds.

"If they do show up you'll often have them as 'super women' - 'she speaks 12 languages, she had 18 PhDs by the time she was 12'. For me it was really special to write [about] a relatively ordinary 20-something."

'Easy targets'

The Staunch Book Prize was set up last year by writer Bridget Lawless in the wake of the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements. She came up with the idea after judging the BAFTAs.

"I'd been becoming more aware of how many films use rape as part of the storyline, if not the main part," she says.

"I thought, we need more challenges to violence against women in fiction. As it's source material for film and television, it seemed like the obvious place to start."

She says women have been an "easy target" in the thriller genre, which has a tradition of "sexualised violence".

"There's a huge long history of depicting women as vulnerable and prey," she says, referring to films such as Alfred Hitchcock's 1960 Psycho, which was based on Robert Bloch's 1959 novel of the same name.

"It has its place, definitely. But it sits very uncomfortably, I think - and a lot of people think - against what women are fighting for in real life: trying to be taken seriously, trying to get equality in work, pay and every other place."

'Crime fiction got lazy'

The two years since the birth of the #MeToo movement has seen the rise to prominence of female characters who inflict violence, such as Villanelle, the female assassin in BBC Three's Killing Eve, and Eleven, the teen with supernatural powers in Netflix's Stranger Things.

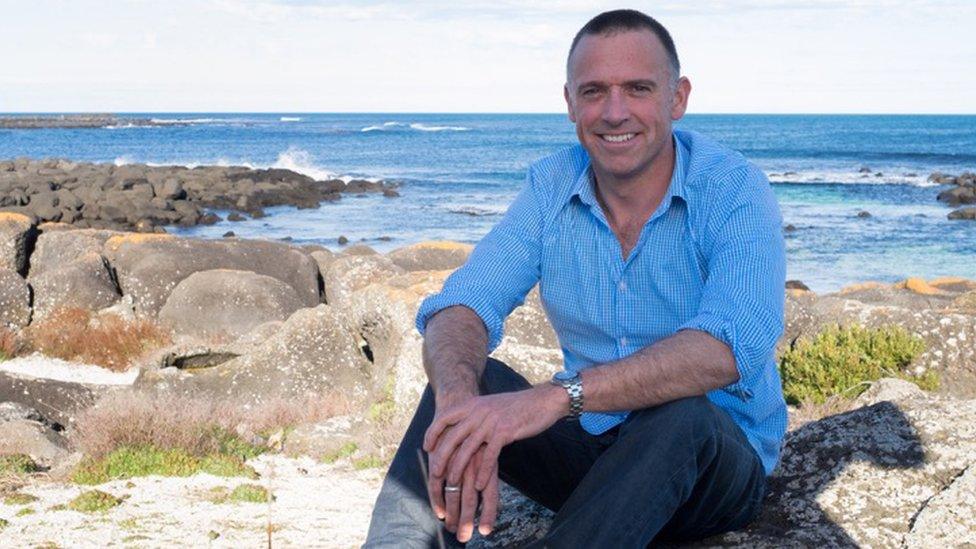

For Jock Serong, an Australian writer who won the prize last year for his book On The Java Ridge, the movement towards "nuanced" female characters began before #MeToo, and "lazy" stereotypes of women as "damsels in distress" are being challenged.

"Part of the reason everybody slipped into laziness was because readers came to expect certain devices to be used in crime plots as much as the writers were using them. It's a two-way street," he says.

"I don't think in the past there's been nearly enough thought about what that represents [and] the message that that sends."

'Silencing women'

The Staunch Prize been criticised by some crime writers as a "gagging order", external that sweeps violence against women under the carpet.

Julia Crouch, author of Cuckoo and Her Husband's Lover, says that while "damsel in distress" clichés are problematic, "lazy stereotypes of crime writing" are also unhelpful.

"Writers of crime fiction that I know feel they have a strong duty to interpret and analyse current society," she says, adding that survivors of domestic abuse and sexual assault can find it helpful to read about these issues.

The prize was created on a "flawed premise", she says, because it celebrates a negative feature - the absence of violence - as opposed to a positive feature.

"What that kind of prize immediately knocks out is the lived experience of millions of women in this country," she says.

"It's a damaging message to send out, to say that 'We just want women to be safe'... it seems to me a bit like silencing women."

Ms Lawless rejects the argument that it is a "gagging order" that ignores lived experiences, saying: "We're not telling anyone what to write or what not to write... But we do challenge the proliferation of fiction which centres women as prey and victims of strangers in gratuitous and voyeuristic detail."

'Important to represent'

Asked whether it is important to celebrate works that don't include gendered violence, Dr Rashmi Varma, who teaches feminist literary theory at the University of Warwick, says it depends on the purpose of the violence.

"If it is gratuitous violence that is meant to titillate and entice, then that is a problem. But if authors represent violence in order to critique it, in order to expose how it works to undermine women, then it is important to represent it," she says.

'Default position'

Samantha Harvey, a British writer who made this year's shortlist, says what happens in reality "ought to be happening in fiction".

"It's not that we shouldn't reflect those things in what we write, but there's also a default tendency to just pick women," she says.

"When you look at books where children have gone missing, it's always a girl who goes missing. Why is it a girl who has to go missing?"

Her own novel, The Western Wind, which is set in a 15th-Century English village, centres around the death of a male victim.

"The violent crimes in most books are against women, and if that's just being done as a default position, unthinkingly, because that's 'just what we do' and how we get readers - because in some troubling way that's what people prefer to read about - I think that does need to be challenged," she says.

"This prize is doing that. It's not saying, 'We should never write about violence against women,' but just 'Can we challenge the tendency to do that too much, and to do it unthinkingly?' If the prize has to go too far the other way to make that point then so be it."

- Published25 October 2019

- Published10 October 2019