Two-thirds of UK homes 'fail on energy efficiency targets'

- Published

- comments

Experts say the UK needs to retrofit homes to make them energy efficient

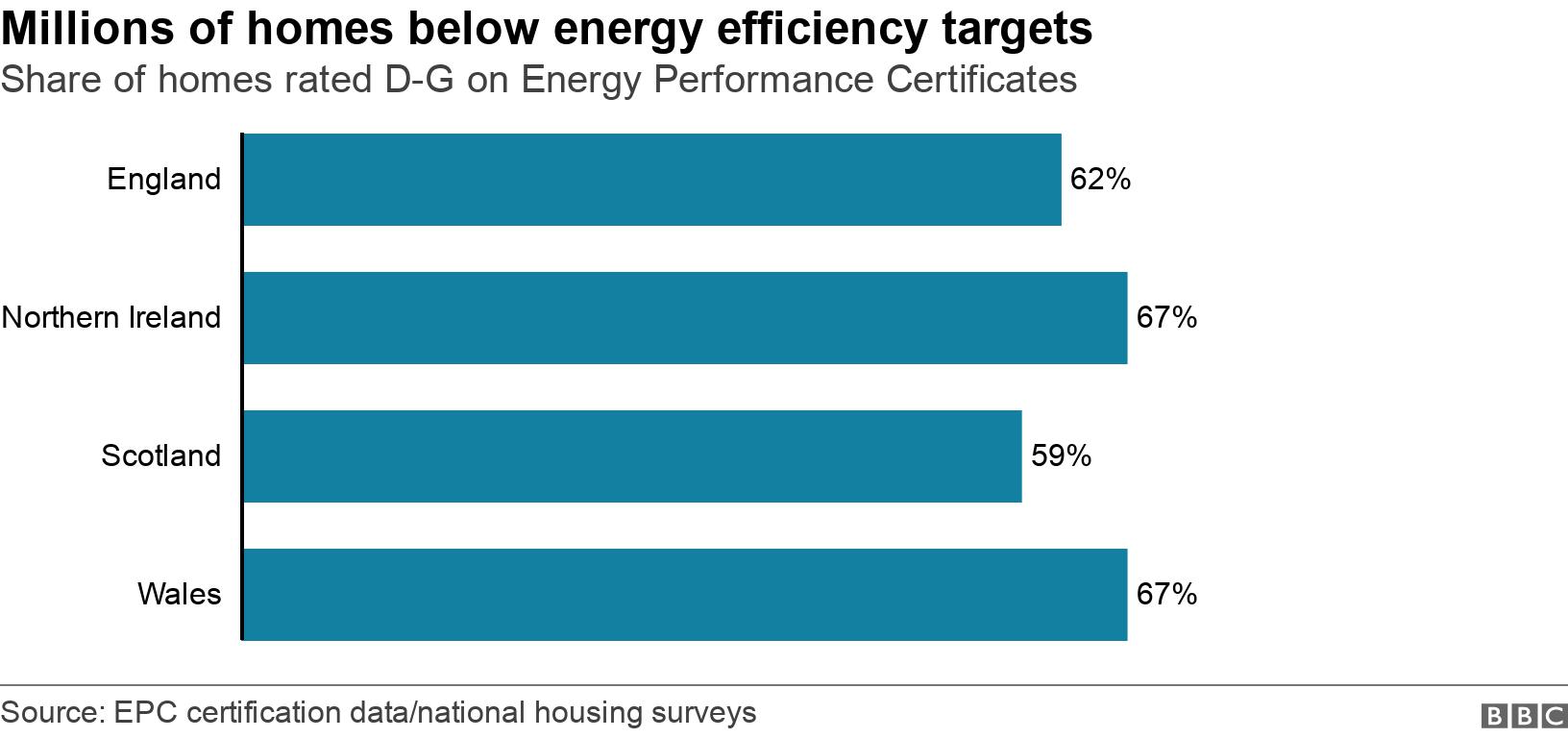

Nearly two thirds of UK homes fail to meet long-term energy efficiency targets, according to data analysed by the BBC.

More than 12 million homes fall below the C grade on Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) graded from A-G.

It means householders spend more on energy bills and pump tonnes more CO2 into the atmosphere than necessary.

The government has said it needs to go "much further and faster" to improve the energy performance of homes.

Experts say retrofit measures are needed because so many homes were built before the year 1990.

Dr Tim Forman, a research academic at the University of Cambridge's Centre for Sustainable Development, said now only a national project of a scale not seen since World War Two, would be enough to help Great Britain meet its 2050 net zero carbon target, which was signed into law in June 2019.

EPCs measure the efficiency of a house by looking at how well a property is insulated, glazed, or uses alternative measures to reduce energy use.

Homes are given a grade between A and G. The closer to A, the more efficient the home, meaning it should have lower energy bills and a smaller carbon footprint. A grade G is at the other end of the scale. C is just above average.

The government had set a target, external to upgrade as many homes to grade C by 2035 "where practical, cost-effective and affordable", and for all fuel poor households, and as many rented homes as possible, to reach the same standard by 2030.

Critics, however, say moves towards achieving that have "fallen off a cliff".

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy said it was investing "over £6bn" towards those upgrades and it was "also exploring how to halve the cost of retrofitting properties and investing over £320m into helping heat homes with lower carbon alternatives, such as heat networks and heat pumps".

It highlighted that from April landlords cannot let a rental flat or house in a new tenancy or a renewal unless the property has a grade of E or higher.

The 65.9 million tonnes of CO2 produced by the UK's homes in 2018, was more than that from power stations which generated our energy supply, according to annual greenhouse gas emissions data.

"We need to throw everything we have at it [energy efficiency]," Dr Forman said.

"There's a desperate need to do something, not in 10-15 years, but now."

The BBC's Shared Data Unit analysed the grades awarded to more than 19.6 million homes across the UK since their introduction in 2007.

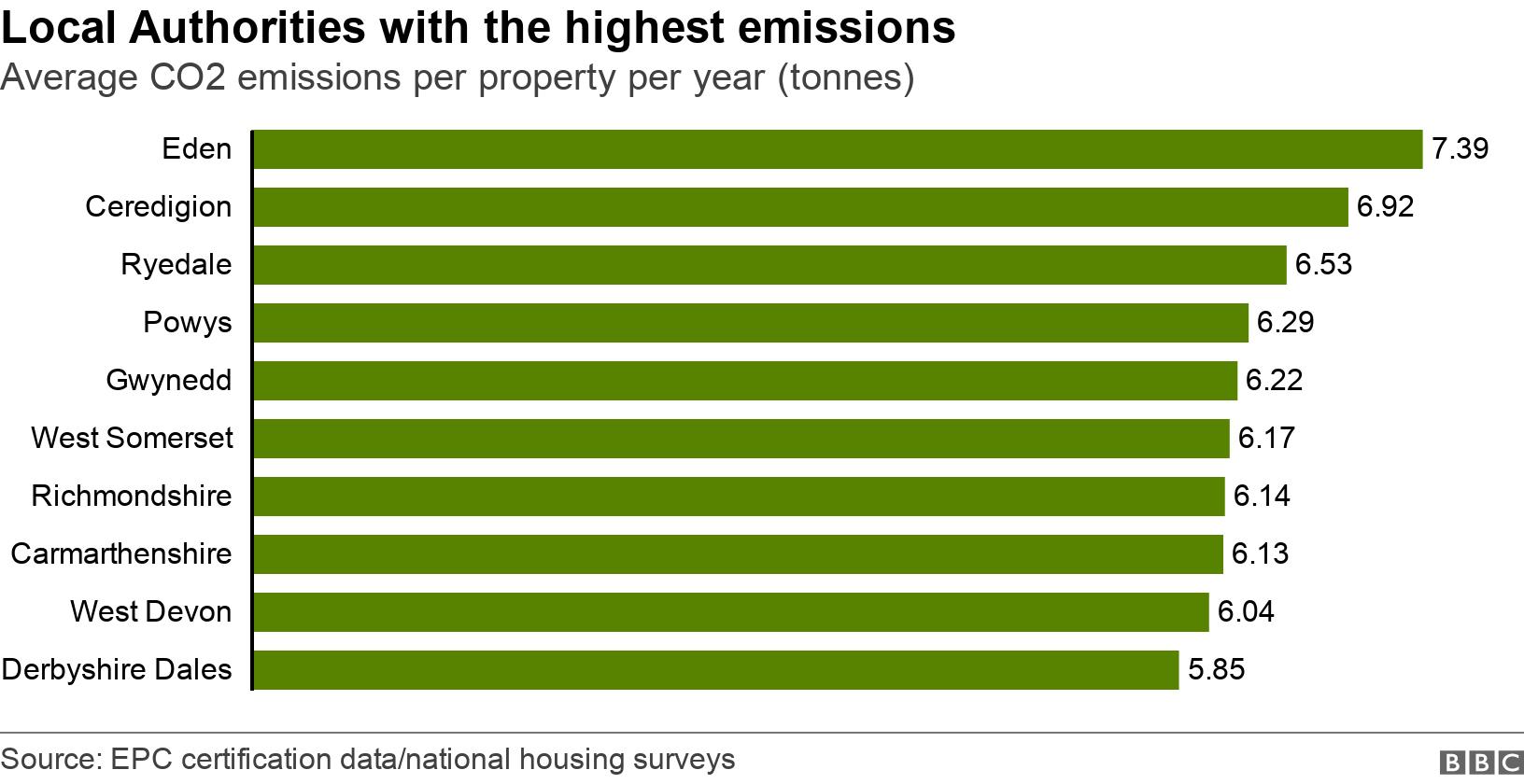

The local authorities across England and Wales with the highest average CO2 emissions per household were all rural areas.

Similarly, the biggest domestic producers of CO2 in Scotland were in the islands and highlands.

Peter Smith, from national fuel poverty charity National Energy Action, said there was "definitely a rural/urban split" especially in areas not connected to the gas grid.

"They tend to live in the least energy efficient housing, which tends to be older and uses fuels like LPG or solid fuels," he said.

"At a high level...there needs to be a push to improve all homes, but to do this it needs to have the same infrastructure priority as HS2 or building a third runway [at Heathrow]."

"Since 2012 it [tackling energy efficiency] has fallen off a cliff."

That decline has been blamed by some on the Green Deal scheme. It came into force in 2012 but was axed three years later amid criticism it was too complicated and had been poorly implemented.

Energy efficiency is a devolved issue and the ruling authorities in Scotland and Wales provide additional funding for measures including low-interest loans, for those with the ability to pay, and free measures to low-income households at risk of fuel poverty.

Under new Welsh government plans announced earlier this year, every new home built there after 2025 will be only heated and powered by clean energy, and produce up to 80% less CO2.

One suggestion to increase the pace of change could be to offer financial incentives for people to make improvements at significant "trigger points" in their lives such as when they moved home or had already planned other renovations, Jenny Hill, of independent advisory body Committee on Climate Change, said.

Bigger borrowing powers for local authorities to spend on new social housing, could also drive the building of more energy-efficient housing across Great Britain, some experts suggest.

One example is Goldsmith Street in Norwich, which won the Stirling Prize for architecture, and is built to the Passivhaus building standard.

Goldsmith Street in Norwich has won plaudits

It means the homes use new technologies to ensure low energy use, the windows are triple-glazed and the homes are positioned so the sun heats them in the winter and helps them stay cool in summer.

Passivhaus buildings can, however, be around 8% more expensive to build than a traditional house, but they are intended to be more efficient and cheaper to run.

Those standards can also be retrofitted to existing homes.

Kim Ratcliffe lives on Erneley Close, in the Longsight area of Manchester, a former council estate retrofitted to Passivhaus standards five years ago.

The 55-year-old mother-of-two said: "In the past we had to use fan heaters because it was so cold and because we could not afford to put on the radiators.

"We would get through £12-£13 a day just to run the heaters.

"I have never had to put the heating on since it has been redone.

The cladding at Erneley Close turns different colours in different lights

"The rent has gone up a little bit, but the heating bills are so much lower that it is still saving us money."

John Palmer, from the Passivhaus Trust which sets and administers the standard, said interest from councils and housing associations could influence change.

"Developers aren't interested in running costs, they build it and walk away.

"Local authorities and housing associations are. They have a vested interest in keeping running costs as low as possible for themselves or for tenants."

Depending on the age and nature of individual properties, the cost of retrofitting energy efficiency measures could range from £18,000 to £150,000, Dr Forman said.

Jenny Hill said that while financial incentives were important, "a robust legal standard" would create ongoing demand for these measures.

"That is what gives the market confidence that demand will be there in the long term. It makes them willing to invest in jobs and skills," she said.

More about this story

There will be more on this story on Inside Out on Monday 9 March on BBC One at 19:30 GMT.

The Shared Data Unit makes data journalism available to news organisations across the media industry, as part of a partnership between the BBC and the News Media Association. This piece of content was produced by a regional journalist for ITV working alongside BBC staff.

For more information on methodology, click here., external For the full dataset, click here., external Read more about the Shared Data Unit here.

Additional reporting team: Anna Khoo, Alex Homer, Paul Lynch, Pete Sherlock

- Published16 January 2020

- Published16 January 2020

- Published14 January 2020

- Published21 January 2020