In search of the real Christine Keeler

- Published

Christine Keeler was just 19 when she became embroiled in a sex scandal that would bring down the British government. Not only was she vilified at the time, but the affair stalked her throughout her life. For the first time, a new drama reappraises her character by telling the story through her eyes, writes Tanya Gold.

The Profumo Affair, with its ingredients of sex, aristocrats and espionage, was a scandal so perfect it remains one of the most enduring in modern British political history. It is also a story that is often remembered as an overture to the Swinging Sixties - a tale of sexual liberation and hope, but one in which everyone who took part was punished.

It was 1961 in London and 19-year-old model Christine Keeler was sleeping with both John Profumo, 46, the Conservative Secretary of State for War, and Yevgeny Ivanov, 31, a naval attaché at the Soviet embassy, and a spy. Keeler's enabler was her friend Stephen Ward, an osteopath and amateur artist who moved in aristocratic circles and introduced her to both men.

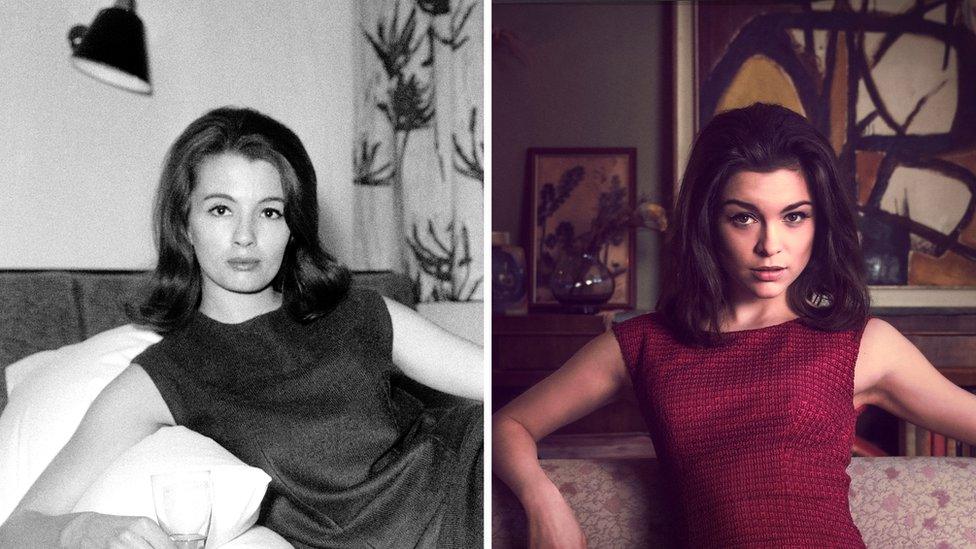

After the affair was exposed, Profumo resigned, Keeler went to prison for perjury and Ward took his own life. The following year, Harold Macmillan's Conservative government fell - the Profumo Affair had exacerbated its rot. It is now dramatised, in minute detail, in a six-part BBC series The Trial of Christine Keeler by screenwriter and novelist Amanda Coe. Sophie Cookson stars as Keeler, Ben Miles plays Profumo and James Norton, Ward.

Unlike Michael Caton-Jones's 1989 film Scandal, which focuses on Ward (John Hurt) and is over-jolly for the subject matter, Coe prefers to concentrate on Keeler herself.

"The story had never been told from the point of view of the woman at the centre of it," says Coe.

Ben Miles as John Profumo and Sophie Cookson as Christine Keeler

Who was Keeler? Superficially, a series of archetypes, and that is surely why she fascinated. You can project anything onto an archetype who is usually portrayed, as Coe says, as "a dead-eyed siren". Prime Minister Harold Macmillan called her a "tart", while Ward always called her his "little baby". Ward was fantasising about Keeler's compliance, and Macmillan was merely wrong.

Keeler, who died in 2017, was never a prostitute. She was something more interesting and complex - a young woman who liked sex in an era when good girls didn't, or at least they pretended that they didn't. And so, Keeler became an unfortunate cipher for sexual promise when repression was a national disease. The term "prostitute" is merely a guilty slur.

Later, for anyone who still cared, she was an object of pity, occasionally photographed by the tabloids as she tried and failed to thrive after the scandal, her famous beauty gone and with it, her small power.

Christine Keeler shortly before her trial

Keeler was born in Uxbridge, Middlesex, in an unhappy and impoverished home - a house made from two converted railway carriages. Her father abandoned her mother during World War Two, and at one point, Keeler was removed from her mother when it was discovered the child was suffering from malnutrition.

Keeler had the complex gift of beauty, and men used her for it. Her stepfather, she reveals in her memoir Secrets and Lies, assaulted her when she was 12 and asked her to run away with him because he did not love her mother. Local fathers assaulted her when she babysat their children. She left school at 15 without qualifications and became pregnant by an American serviceman. She apparently tried to abort the child herself, but failed, and it died at six days old. In the 1950s, there was no pity for young women who suffered as Keeler did, but there was much reproach.

Secretary of State for War John Profumo at Sandown Park Racecourse in 1963

She ran away to London and became a show girl at Murray's Cabaret Club in Beak Street, Soho, dancing topless for £8.50 a week. It was here that she met Stephen Ward. We might presume now that she was still suffering from the early neglect, the assaults and the death of her child - certainly Sophie Cookson plays Keeler as unknowable and untouchable.

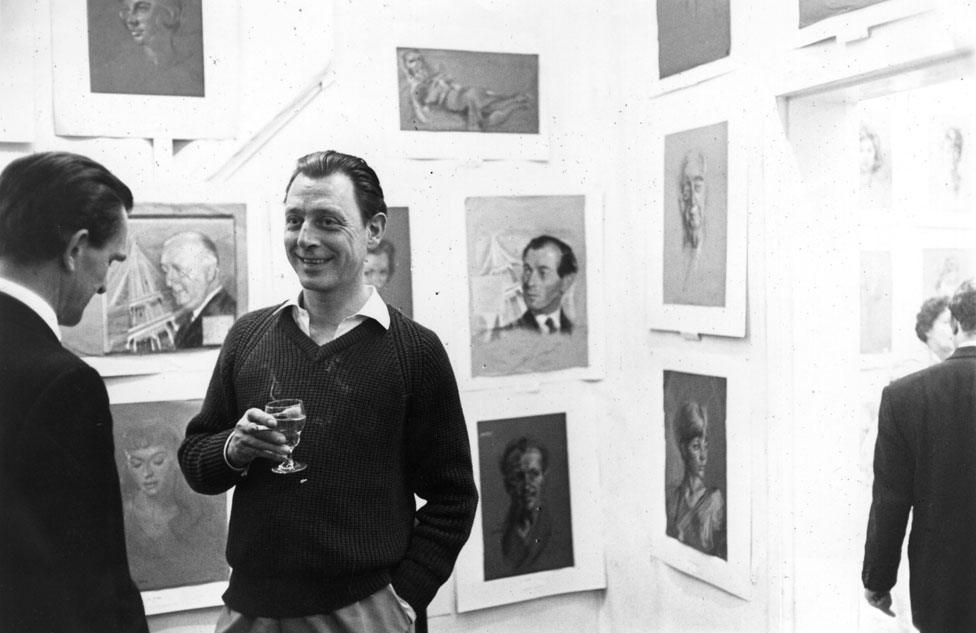

Ward was from a bourgeois background - his father was a Torquay vicar - and he loved to court aristocrats. He also enjoyed the company of working-class girls like Keeler. She became one of his protégées, and while he never slept with her, he did take her to orgies and eased her into love affairs that would benefit him socially. She was his living, breathing toy. He groomed her - although in Coe's telling and James Norton's tender and bewildered performance, Ward, too, is vulnerable - a man on the outside looking in. Perhaps this is what bound him and Keeler together.

Stephen Ward at one of his art exhibitions

Lord Astor, who slept with Keeler's friend Mandy Rice-Davies, allowed Ward to rent a cottage in the grounds of Cliveden, his country home. It was there in July 1961, while swimming naked in a pool in a walled garden, that Keeler met the 5th Baron Profumo, who was married to the fêted actress Valerie Hobson. She says he chased her, trying to remove her towel.

They had an affair, but it lasted only months.

Why did she do it? I suspect that after her youthful experiences of abandonment and betrayal, she wanted to please men, and Ward in particular, since he noticed her and appeared to cherish his "little baby". Was it easier to say yes, and to do what they wanted - since it was all they wanted? Keeler's testimony about Profumo suggests that tenderness from men could move her: "I enjoyed it," she wrote of the sex, "for he was kind and loving afterwards".

John Profumo with his actress wife, Valerie Hobson after resigning from his post

But not everyone was "kind and loving" in this context. There were many beatings for a beautiful girl who liked sex. She was involved with Jamaican jazz singer Aloysius "Lucky" Gordon, who raped her and held her hostage; it was that affair that exposed the wider scandal, and led to her prison sentence. Keeler had already left Gordon when he was wounded in a fight with Johnny Edgecombe - another of her lovers. Edgecombe stalked Keeler to Ward's flat in Wimpole Mews, central London, in December 1962 and fired gunshots at the front door. The police were called, the press was alerted, and the Profumo Affair began to unravel.

Sophie Cookson as Christine Keeler, with Nathan Stewart-Jarrett as boyfriend Johnny Edgecombe

Just two years earlier, the Portland Spy Ring had been uncovered, leading to the conviction of five people for passing secrets to Russia. Now, the confection of espionage (Keeler had been sleeping with a Russian spy), sex, aristocracy and race - Edgecombe and Gordon were both of West Indian descent - was irresistible. Keeler, from anger and naivety, sold her story to the newspapers and became famous and reviled at the same time.

"Lucky" Gordon was jailed for assault, but when Keeler withdrew her testimony, she was imprisoned for perjury. Ward, meanwhile, was punished with a spurious accusation of living off the immoral earnings of prostitutes. In fact, Keeler and Rice-Davies, who had both lived with him, had merely contributed to the telephone bills and repaid money he had lent them. But the order was given to Scotland Yard to "get Ward" and they obeyed. Memories are long. A submission to review the conviction in 2017 was denied; the official material is sealed until 2046.

The wreckage of the affair was cast far and wide. No-one escaped uninjured, except Ward's aristocratic friends, who promptly - and inevitably - dropped him. Towards the end of his trial, Ward took an overdose of barbiturates. He died three days later. Profumo resigned from the government when it was revealed that he lied to the House of Commons about his affair with Keeler. He spent the rest of his life as a volunteer at an east London charity called Toynbee Hall.

Christine Keeler, October 1963

However, his CBE from Elizabeth II in 1975 signalled society's forgiveness, and he was invited to Margaret Thatcher's 70th birthday party, where he was seated next to the Queen. Lord Longford said he felt more admiration for Profumo than "all the men I've known in my lifetime". In this reading, Profumo remains, eternally, Keeler's victim, and the obituaries after he died in 2006 were kind. Misogyny dies hard.

For Keeler, there was no such redemption - at least, perhaps, until now, when in Coe's telling, she can step out from behind her archetypes and be seen as whole and with agency.

The scandal stalked her throughout her life, particularly after her own sexuality entered the national culture and became part of it - her portrait, by Ward, a talented amateur artist, is owned by the National Portrait Gallery.

She was poorly educated but not stupid, and when she said, "I took on the sins of everybody, of a generation, really", it feels true.

Sophie Cookson playing Christine Keeler and Ellie Bamber playing Mandy Rice-Davies

So, it is gratifying that Coe, in detailing her story so precisely, makes Keeler so human - a young woman who walked blithely through life and made mistakes, for which she paid too high a price. Nor does Coe keep Keeler forever entombed in 1963, the year of her infamy, and the year that she posed for a portrait that has become one of the defining images of the decade.

In the photo, an apparently naked Keeler straddles a chair which has been positioned with its back to the camera.

According to Coe, Keeler had been adamant in later interviews that she had refused to pose naked - that she had in fact worn knickers for the photo, and had pulled them out of the way of the shot.

The "naked" Keeler is just another myth, she says - another example of how she has been misrepresented.

The final scene of The Trial of Christine Keeler looks forwards from that 1963 moment - it has her dancing in a reverie, with closed eyes and upturned arms.

The Trial of Christine Keeler continues on Monday 30 December and then on Sunday nights at 21:00 on BBC One.