Brexit: Five things the UK needs to resolve after leaving the EU

- Published

The UK might have left the EU but many questions remain unanswered.

Here are just some of the hurdles facing the UK after Brexit.

1. Agreeing a trade deal with the EU

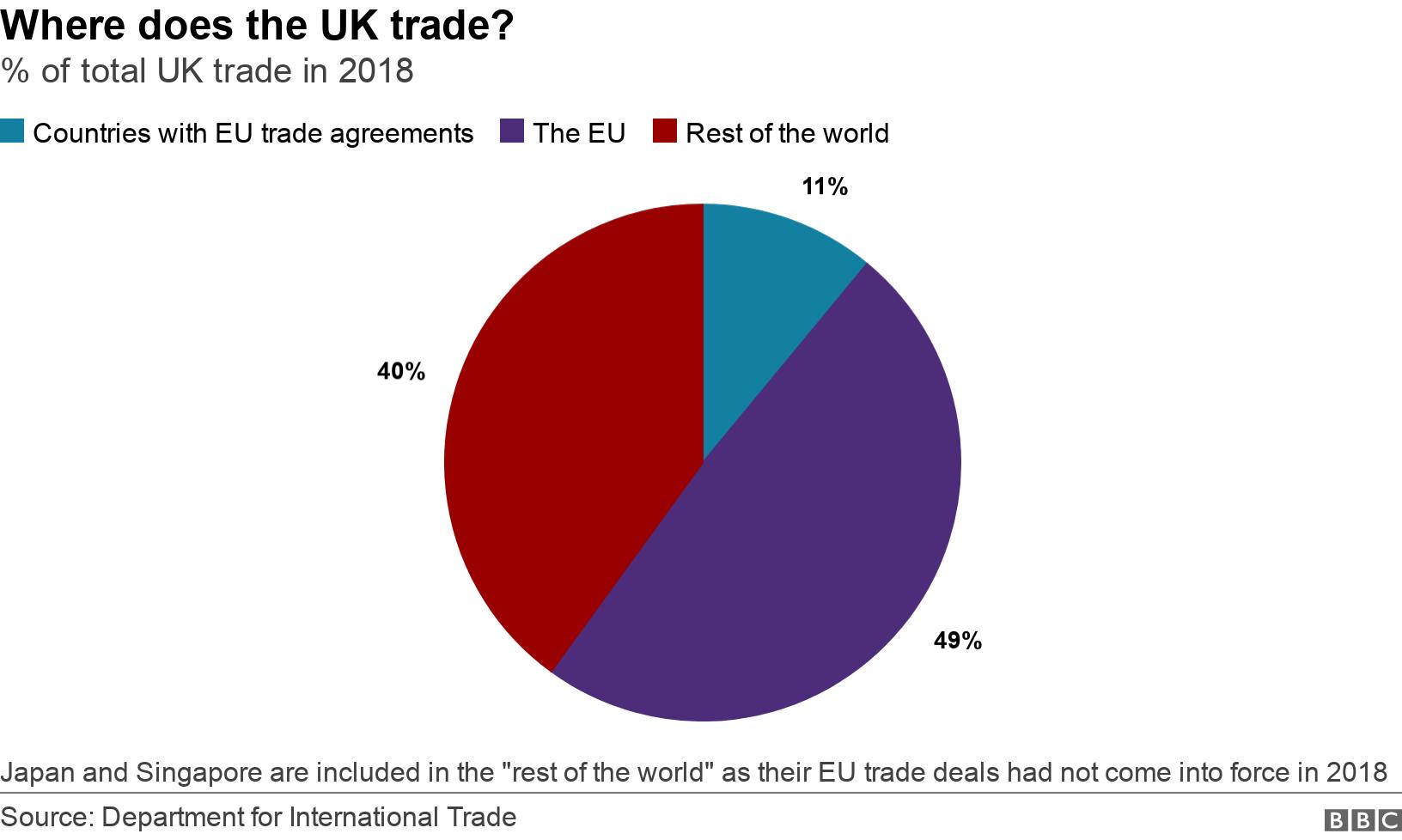

This legal departure from the EU means the UK can finally start formal trade negotiations - both with the EU and countries around the world, like the US.

The government is determined not to extend the post-Brexit transition period - to discuss the future relationship with the EU - beyond the end of 2020. This means the timetable for getting an agreement with the EU is extremely tight.

Formal talks are expected to begin in March, once the remaining 27 EU countries have agreed on instructions for their negotiators.

Getting any agreement finally signed off and put into practice will take a couple of months towards the end of the year. So, realistically, that only leaves time for a fairly basic free trade deal to emerge, with plenty of issues still up for discussion once the transition period is over.

The government talks about getting a "zero tariff, zero quota" deal on goods, with no border taxes and no limits on exports and imports.

But there are a host of issues to be dealt with if the aim is to keep trade flowing as smoothly as possible, and that is before we mention the services sector.

From financial and business services to the food and drinks industry, this accounts for more than 80% of UK jobs., external

It is of course in the interest of both sides to get a deal done, but it remains a massive task. Expect disputes about fisheries, fair competition, the role of the European Court of Justice and more.

It is possible that no deal will be done in time, which will generate a fresh crisis in UK/EU relations as 2020 draws to a close.

2. Keeping the UK secure

If the challenge to get a trade deal within 11 months is not hard enough, the UK must also agree a treaty to paper over legal cracks in the way countries work together on security.

Policing and security experts in the UK and the EU agree that things will become harder after Brexit.

For instance, the UK no longer has a place on the team that manages Europol, the agency that co-ordinates major investigations into Europe-wide organised crime.

This means the UK's priorities - such as concerns about smuggling people or arms across the English Channel - may, slowly, fall down the pecking order.

Brexit means that the UK no longer has anyone in a senior position at Europol

British police officers can, for now, still use EU systems to check criminal records of foreign nationals, or alerts on wanted people from around the continent.

But access to that information could either end or become harder, because many member states have their own specific laws governing data-sharing beyond the EU.

The government is trying to think ahead.

It has, for instance, pledged to pass laws to ensure the same fast service the UK has enjoyed from the European Arrest Warrant - which allows suspects to be sent to another country for trial - if a deal cannot be struck. Everyone, on both sides, wants that.

The question is whether it is legally doable - and if so, can it be done by January 2021?

3. Making sure the food keeps coming

From farming and fishing to manufacturing and retail, the UK's food and drink sector adds £460bn to the UK economy every year,, external employing more than four million people.

It represents a fifth of UK manufacturing, by far the biggest chunk of the sector.

So there is some nervousness about what will happen to the complicated way that food and drink makes its way to consumers after the end of the transition period.

A third of people in the industry are from outside the UK, with many from Eastern Europe. What happens if the number of such workers is restricted because of the introduction of a minimum salary being imposed for migrants?

When it comes to trade, there is the prospect products may have to be opened and checked at borders which could add expense and cut the shelf life of fresh food.

And the Food and Drink Federation, a body representing food manufacturers, says the most complex challenge is around trying to get a trade deal with Europe that satisfies what are called "rules of origin".

UK manufacturers use a mixture of domestic and internationally-produced ingredients, which would not be allowed under rules included in recent EU trade deals.

4. Building a new role in the world

The government has a huge task ahead to establish the UK's place in the world after leaving the EU.

Ministers have to work out what the government's slogan "Global Britain" actually means.

The traditional role of providing a transatlantic bridge between Europe and the US will be put to one side.

Instead, ministers must develop a more independent foreign policy. That could mean less automatic support from the UK for the US, as it focuses more on domestic issues and less on its relations with other countries.

It will mean a new relationship with European allies, not through EU structures, but through smaller existing groups. These include the E3, an informal group made up of the UK, Germany and France, which has worked together on issues like relations with Iran.

The biggest foreign policy challenge will be how to navigate a path between an increasingly stronger China and a defensive US, without the protective membership of the EU.

To that end, Boris Johnson has ordered what he calls an 'integrated review" of the UK's security, defence and foreign policy which is expected to report later this year.

5. Showing that all the arguing was worth it

The protesters who turn up on Westminster's College Green are a lonely bunch these days.

Even the most ardent fan of the EU would have to admit that the heat has gone out of the passionate, and often vicious, political fight of the last few years.

The challenge for Mr Johnson is now to show to the public that all the disruption, all the arguing, was actually worth it.

That will not be easy. Brexiteers are keen to make the most of the powers that will come back to the UK from Brussels as soon as possible.

But now we are in the departure lounge - the transition period where the status quo will stay pretty much the same.

Even if you popped champagne on Friday night to celebrate the UK leaving the EU, when you woke up on Saturday morning not much would have actually felt very different.

Can the enthusiasm and excitement on that side be managed?

And even though the stay or leave debate is now at an end, some voters still believe we are setting off on a path of folly. And there are big fears that a trade deal No 10 wants simply is not doable by the end of the year.

Mr Johnson would be perfectly happy if after Friday, the B-word was never heard again, but he needs to show to the public on both sides it was worth it.

He has already found a place in the history books, but the chapter is not yet complete.

What questions do you have about Brexit and how it will affect you in the future?

In some cases your question will be published, displaying your name, age and location as you provide it, unless you state otherwise. Your contact details will never be published. Please ensure you have read our terms & conditions and privacy policy.

Use this form to ask your question:

- Published13 July 2020

- Published30 January 2020