What does healing the Brexit divide mean?

- Published

The moment of Brexit is a time to "find closure and let the healing begin", according to Prime Minister Boris Johnson. But what does "healing" involve?

If there is one thing that people on both sides of the referendum debate agree on it is that, at times, the argument became far too hostile. In the House of Commons, on social media and in the streets, passions became inflamed.

An official statement from the prime minister earlier this month said now was "a moment to heal divisions". It was also announced that Brexit would be marked with a Downing Street light display, the hoisting of flags, a countdown clock and the minting of a commemorative coin.

While many of his supporters want to celebrate leaving the European Union, there's little sign that these events have healed political divisions.

On the other hand, it's not clear how the decision of the SNP to fly an EU flag outside the Scottish Parliament building was going to bring people together.

To heal, we need to understand the nature of the divide. Why do people feel so strongly about Brexit? What are the values that lie behind the slogans and insults?

Two visions?

There is a danger in trying to characterise the Leave/Remain split too rigidly. The practice of describing people, places, regions and nations as "Leave" or "Remain" risks polarising the argument with a binary description that fails to reflect the nuance behind the choice and the result.

For instance, London is often described as a "Remain city". But more Londoners voted to leave the EU than voted for Remain-supporting Sadiq Khan as mayor. Meanwhile, even in that most pro-Brexit town of Boston in Lincolnshire, a quarter of those who took part opted to remain.

Voters had a whole list of reasons for choosing to support one side or the other, often weighing up different arguments. No place was 100% for leaving or remaining in the EU.

But new opinion polling, commissioned by the BBC and the Campaign for Social Science, external, helps us understand the core beliefs associated with the way people voted.

The survey, conducted by Ipsos MORI, asked people to say which propositions came closest to their view.

The phrase "influences from other countries and other cultures make Britain a better place to live" was supported by a majority of Remain voters (56%), but just a quarter (23%) of Leave voters.

The alternative proposition - "influences from other countries and cultures threaten the British way of life" - was supported by just 18% of Remain voters but 52% of Leave voters.

A similar result was found with a slightly different proposition. The phrase "Britain will be stronger if it is open to changes and influences from other countries and other cultures" was supported by 58% of Remain voters but just 22% of Leave voters.

The alternative - "Britain will be stronger in the future if it sticks to its traditions and way of life" - was supported by 56% of Leave voters and just 14% of Remain voters.

Along with other polling data, Remain voters emerge as significantly more likely to celebrate Britain's diversity and say they feel European. Leave voters are more likely to say Britain's history, heritage, pageantry and Christian tradition are important to their national identity.

Leave voters appeared more patriotic, proud of their nationality and more likely to suggest their country was better than others. Remain voters placed more importance on being part of the international community.

What is suggested by the survey is two visions of Britain - one which seeks to protect tradition, heritage, culture and familiar way of life, another which is happy to embrace change and keen to be part of a global conversation.

They are not mutually exclusive ideas - there is always a balance to be found between continuity and change. We can all feel that we want to protect tradition and be open to new ideas. It is a matter of emphasis.

But the reason that this debate has inspired such passions is that it goes to the kind of country we want to live in, its priorities and values.

Echo chambers

In that context, what does healing look like?

Culturally, British politics and public discourse tend to be adversarial. The House of Commons is designed to pit one side against the other. Compromise is often portrayed as weakness. Consensus-building seen as alien to our political tradition.

But conflict-resolution experts say healing doesn't mean conceding the argument. It is about understanding and valuing the views of people with whom you don't agree.

It is not about trying to change people's minds or prove them wrong. It is about "respectful disagreement".

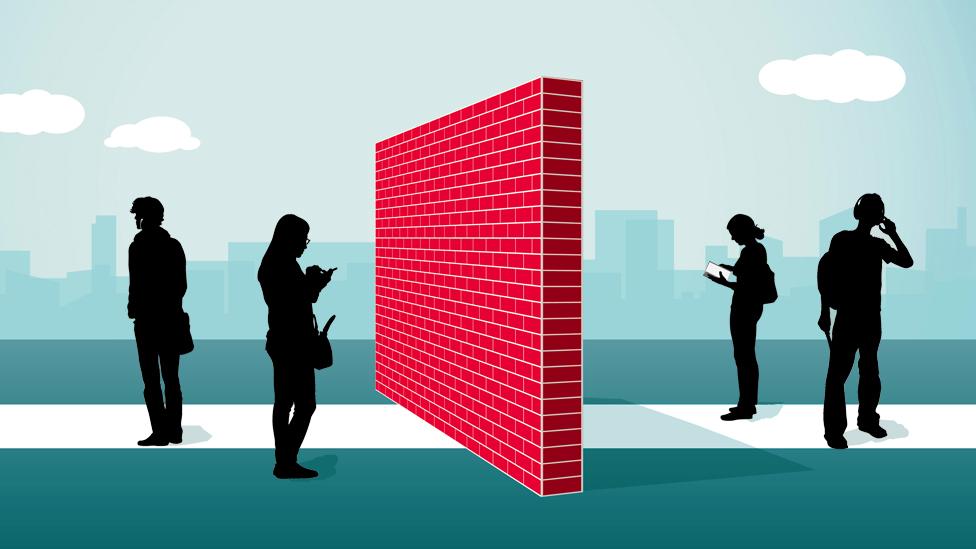

Part of the problem is that it's increasingly easy to live our lives in echo chambers, surrounding ourselves with those who endorse our personal view of the world. On Facebook and Twitter, we naturally exclude those whose views we don't like.

The newspapers and websites we choose, the books we read, the pubs and cafes we frequent, the films we watch - all of them are to some extent selected because they bolster our views and values rather than challenging them.

Indeed, when we do find ourselves hearing opinions at odds with our own core beliefs, it can feel quite upsetting. The views of people we disagree with have a much bigger psychological effect on us than the voices of those who think like us.

Healing the divide, it seems, is going to require us to get out of our comfort zone, out of our bubble.

"More in Common" is the name of more than one body trying to understand this situation. A foundation set up in memory of the murdered MP Jo Cox organises community events which encourage people with different views to come together and explore what unites rather than divides them.

A separate research organisation operating in the UK, US, Germany and France, describes its mission as working to "address the underlying drivers of fracturing and polarisation, and build more united, resilient and inclusive societies".

This year they will be teaming up with organisations and institutions to see what role they can play in "bridging divides" in Britain. One charity they already work with is the Roots Programme which takes people from different walks of life and gets them to "meet and eat, talk and debate", physically removing them from their "bubble".

The first pair to take part were Ben Lane, 31, a Remain-supporting, north-London-dwelling former business strategy consultant, and Peter Curtis, 47, a community football coach from Sunderland who voted to leave.

Both men acknowledge their exchange visits could have been better.

"It was quite depressing going down to London and seeing the money flying about," said Peter, a former construction worker who now earns less than £10,000 a year in Sunderland.

For Ben, the experience made him embarrassed that he played no role in his community, despite his prestigious job as a charity chief executive.

But they now both feel optimistic about the healing of the nation after Brexit.

Ben said: "One of the worst ingredients for healing is uncertainty, and now we've got more certainty.

"It definitely means we can try and galvanise around something."

Helpfully, the phrase "more in common" has some truth to it in the UK. Compared with the US where the liberal/conservative divide runs along almost every area of policy, here there is still broad national consensus on many key issues - taxation, welfare, the NHS, abortion, gun control or homosexuality.

That is not to say that everyone agrees on everything, but it is more likely there will be some common ground where people can gather to explore the aspirations and values they share.

Healing the Brexit divide, though, needs to be more than a group hug. It also means dealing with the consequences of a very fractious and unpleasant period in our politics, a time when many questioned the effectiveness of our system of governance and when confidence in our democracy was shaken.

BBC Crossing Divides

A season of stories about bringing people together in a fragmented world.

Renewing democracy

Tellingly, all the big political parties included proposals for democratic renewal in their manifestos. There was consensus, at least, on the need to take a close look at how power works.

The Brexit vote itself has been interpreted as a cry of pain from communities which felt that their voice was being ignored, that decisions affecting their lives were being taken without consultation or discussion in anonymous offices in Westminster or behind mirrored glass in Brussels.

Politicians of all stripes appear to accept the need to listen to and respond to those concerns, finding ways to help people feel they have a genuine connection to power.

The government intends to create a Constitution, Democracy and Rights Commission that will be instructed to come up with proposals to "restore trust in our institutions and in how our democracy operates".

No details have been given on the terms of reference or make-up of this new body, although there have been suggestions that it may be asked to look at the balance of power between government, MPs and the judiciary after the Supreme Court ruled that Boris Johnson's suspension of Parliament last autumn was unlawful.

Already, some have argued that might be interpreted as Brexiteer vengeance rather than a sincere attempt to heal a wounded democracy.

Such speculation helps explain why constitutional or democratic reform is tricky for government or even for Parliament. Any adjustment to the architecture is likely to have implications for the power of ministers and MPs.

That is why civil society has stepped into this space, looking at ways to involve citizens directly in any redesign of the British constitution - trying to take party politics out of the process and give power to the people.

Citizens' assemblies are increasingly used by governments around the world to find answers to the trickiest of problems - abortion in Ireland, nuclear power in South Korea, energy policy in Texas, waste recycling in South Australia.

More on Brexit

A randomly selected cross-section of the public is recruited to consider a policy question through rational, respectful and reasoned discussion. They engage with information and arguments around a topic before agreeing on a proposal for consideration by lawmakers.

UK parliamentary committees have held citizens' assemblies on climate change and social care to help understand what really matters to informed voters. In Scotland, a randomly selected assembly is currently considering the nation's governance, with its recommendations to be considered by the Scottish Parliament.

Over the next two years, the Citizens' Convention on UK Democracy will attempt to engage 10 million people in what it describes as a "UK conversation". Thousands will receive a formal invitation to participate in a convention, their names selected by civic lottery.

Among the issues that will be considered are the voting system, the future of the House of Lords, devolving power to local and regional bodies, how politics should be paid for and whether the UK should have a written constitution.

A number of senior MPs from across the political spectrum have agreed to help ensure that the conclusions of the convention are considered by Parliament.

There are other initiatives working in the same area, all convinced that the divide exposed by the Brexit debate can be healed only by getting under the bonnet of the UK's democracy, examining its inner workings and looking at ways to improve the performance.

The Hansard Society's most recent annual Audit of Political Engagement suggested 72% of voters think Britain's system of governance needs significant improvement and almost half (47%) say they feel they have no influence at all over national decision-making.

With the arguments and campaigns over Brexit now over, this does seem to be a good moment to consider the lessons of what has been an uncomfortable and at times painful process. It has knocked the confidence and pride Britain once had in its democracy.

If healing is to happen, it will require the nation to ask some searching questions of itself and what kind of country we want to be.

Additional reporting by Callum May