Netflix's Cheer: Inside the world of the UK's student cheerleaders

- Published

The celebration is deafening as Meg Stovell and her team-mates leap from the sprung floor into each others' arms.

"It feels amazing," she shouts as Tina Turner's Simply the Best blasts from the speakers. Weeks of intensive sessions perfecting everything from somersaults to song lyrics have paid off: the Bournemouth University Falcons are the student cheerleading grand national champions.

Cheer, a Netflix documentary series about cheerleading in the US, has taken millions of viewers on a college team's tumultuous journey to the national competition in Daytona Beach, Florida. So how does student cheerleading compare in the UK?

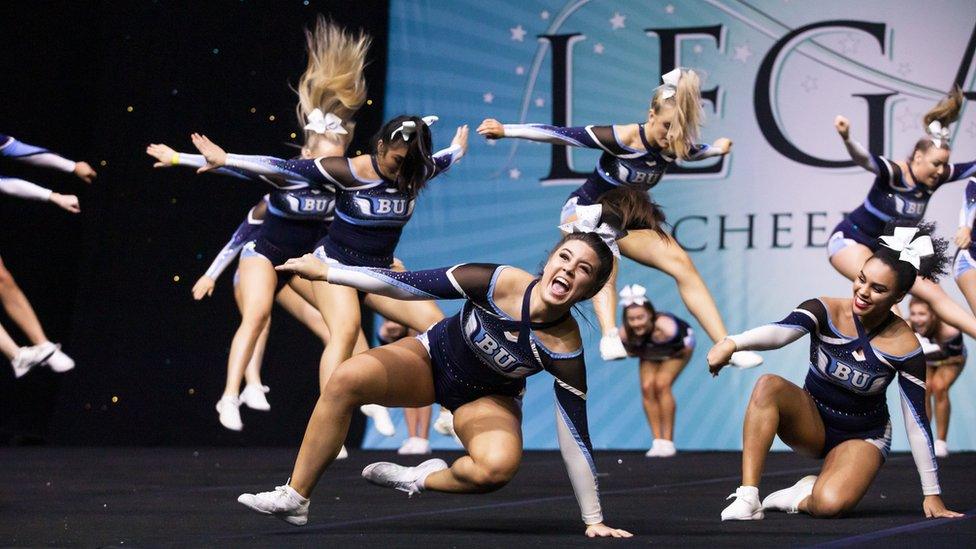

There were more than 25 categories of cheerleading at Legacy, from stunt routines to hip-hop dances

London's Olympic Park is 5,000 miles from Navarro College in Texas, but it seems even further in the February cold outside the Copper Box Arena, where hundreds of students have gathered for Legacy Cheer's university competition.

Inside, though, the stakes feel just as high. One by one, teams clad in sparkly uniforms run on to the stage, desperate to wow the panel of five judges with their two-and-a-half minute routines. They try to mask their nerves with rehearsed smiles as they execute hand springs, pyramids and everything in between - all while lip-syncing to carefully-curated backing tracks. One judge's sole job is deducting points for slip-ups. When a stunt goes wrong, it can be difficult to bring the performance back.

More than 40 universities took part

At one point, an athlete is helped hobbling, in tears, from the mat by her teammates after a move left her with what looks like a twisted ankle.

The standard of UK university cheerleading has a way to go before it matches its cross-Atlantic counterpart. The divisions are ranked from levels one to seven. Navarro College's Cirque du Soleil-style stunts unsurprisingly make them a level seven, while the highest mixed level division at Legacy is three.

One of the reasons is that most student cheerleaders, like Lily Norris, 21, who studies education and psychology at the University of Cambridge, are new to the sport when they enrol. She says cheerleading had a bad reputation when she was growing up in Southend, Essex.

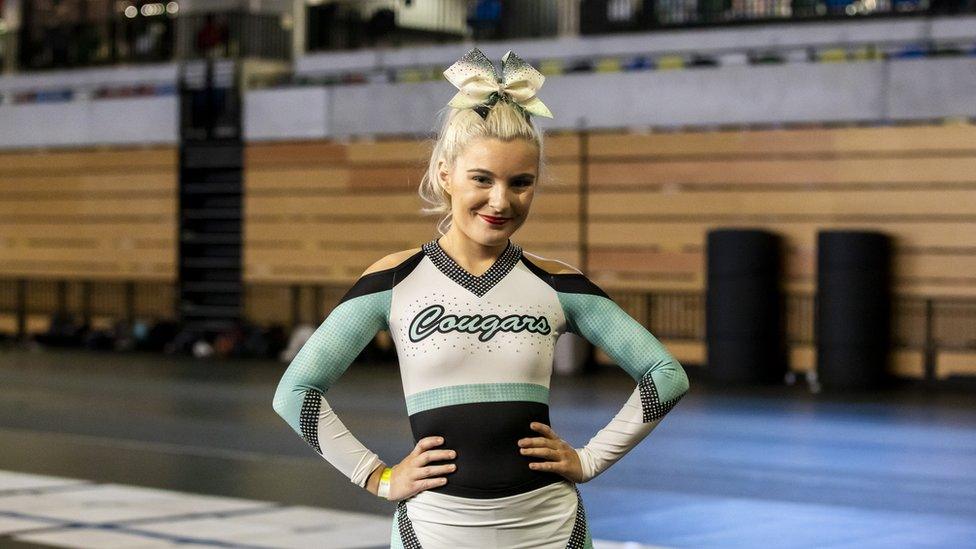

Lily Norris hopes Netflix's Cheer will raise the profile of the sport and help them get the same funding as other teams

"A lot of people just thought of it as pompoms - not really athletic, not really a sport," she says. "It has got this stigma associated with it that I think really needs to be broken because it's such a competitive sport."

Competitors complete feats, tricks and complex balances

Although it was born on the sidelines of American football fields - and was originally a men's activity before women took over during the First World War - today cheerleading is a sport in its own right, geared towards competitions. In the UK, around 89,000 athletes compete at regional and national level. Legacy is just one of a number of competition organisers, holding events for everything from children's "all star" teams which train specifically for competition, to the student teams in February's competition.

The sport is being taken ever more seriously, especially since England's national team won gold in the World Championships. SportCheer England, a new national governing body, hopes it will be officially recognised by Sport England within the next two years, and eventually be incorporated into the Olympics.

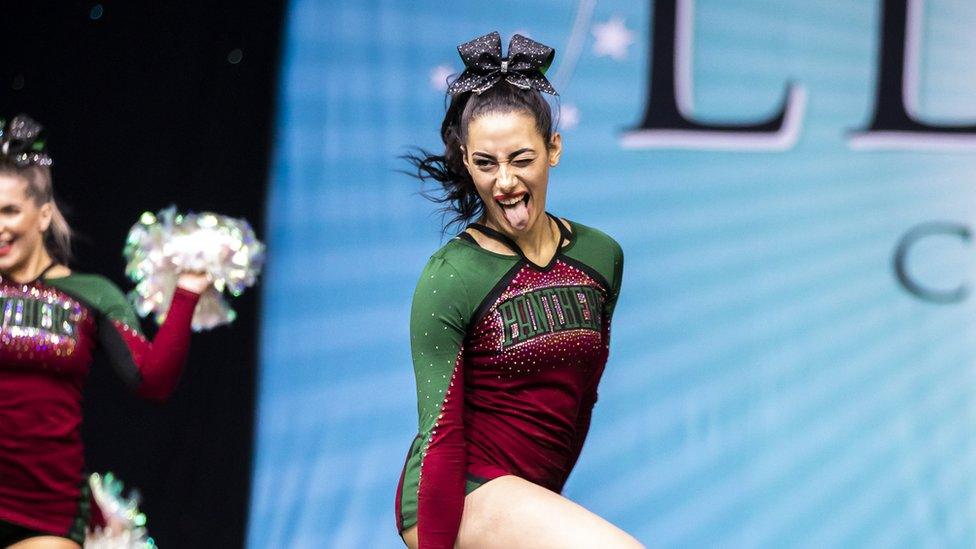

Pompoms aren't often used in routines, but still feature in "pom dance" - its own category

But it is still not nearly as well resourced as it is Stateside, says Andrea Kulberg, a former cheerleader for the University of Texas, who founded Legacy with her twin sister. Breathing a sigh of relief backstage as she removes the earpiece she has been wearing all day, she says: "It's just a matter of time. It hasn't had time to evolve to that stage."

Andrea accepted her first trip to the UK because she had been diagnosed with kidney cancer and wanted to tick England off her 'bucket list'

Andrea still lives in Houston but flies to the UK for competitions. And her first experience here, 21 years ago, couldn't have been further from Friday night shows in front of packed-out stadiums. She had been invited to consult on the sport for a competition in Norwich, where judo mats had been pushed together in a sports hall. The judges asked her how long the routines were meant to be.

"The competition ran two hours behind schedule and the DJ got up and left because he had another gig," she laughs. "I remember thinking: 'I want to help fix this'."

She believes the standard of student cheerleading is now "shifting" because the sport has been growing at a junior level, and athletes who took part as children are now going to university.

A spontaneous dance-off breaks out shortly before the results are announced

In one episode of Cheer, Navarro College's formidable coach, Monica Aldama, says she likes her female cheerleaders to have a certain "look". But Laurel Boxall, the 19-year-old secretary of the Oxford Sirens (the Cambridge Cougars' main rivals) says they take on new members based on ability and personality.

Laurel Boxall says the uniforms and glamour help make the routines "look easy"

"I like that we're not all just carbon copies of each other," she says.

That said, it would be impossible to ignore the myriad of hair bows and fake eyelashes in the Copper Box Arena. Lauren Tyler, 21, and the rest of the Southampton Vixens spent the evening before the competition applying fake tan. She says they push themselves physically like any other type of athlete - having broken multiple ribs and wrists herself - but the makeup and hair "play into" their performance.

More and more student athletes cheered in "all star" teams, which focus on competitions, as children

Joanna Cuthbert, chairwoman of SportCheer England, says the sport's glamorous side can help attract girls who otherwise might not engage in sport.

"It perhaps appeals more than being out on a muddy pitch in the pouring rain," she says, adding that it has a more athletic look at an international level.

Meg Stovell (right), pictured with teammates Olivia Martin and Harry Day, had to fill in last minute after another athlete was injured

The aesthetic can make recruiting men a challenge, says Meg. Her teammate, Harry Day, 20, was adamant that he would join a gymnastics team at Bournemouth University's freshers' fair, but his friends convinced him to try cheerleading.

"The first couple of sessions I wasn't so sure, because it was really dancey," he says. "Then I just got into it."

The Bournemouth University Falcons were named winners of the highest mixed-gender category and overall champions, but had to hold in their joy when the runners-up were announced, as pre-emptive celebration is against cheerleading etiquette

A striking similarity to the Navarro students is the students' sense of commitment to their teams and the sport.

"No one is in for themselves," says Lily. "When one person's missing, it sounds really clichéd, but you can't put the pyramid up. You need to have every single member of the team present."

The Brunel Blizzards had a nervous wait before being named runners-up in the highest mixed category

And pre-competition rituals are not unique to the Navarro team. The Southampton Vixens touch their toes in unison before performing, while the Oxford Sirens read each other motivational notes. They even have "mat talk", when team members motivate their fellow athletes during practices.

"Everyone is telling each other to be a Jerry," laughs Laurel, referring to one of the Cheer stars.

SportCheer England recently conducted the first national survey to find out how popular cheerleading is among non-competitive athletes as well as competition participants

The students stress that while the original role of cheerleading - as implied by the name - was to motivate other teams, they are now the main event.

"If we were just on the sidelines we probably wouldn't do it," says Laurel.

There has been some discussion about whether to rename the sport altogether. Katrina Rutina, the 21-year-old president of the Royal Holloway Bears, says that, even though cheer is an "aggressive" sport in its own right, it would be wrong to deny its origins.

"We are still leading the cheery atmosphere, it's just in its own athletic and professional lane," she says. "It's not other teams that we're cheering on, it's ourselves that we're trying to cheer on."

Photographs by Lily Bungay