Salisbury poisoning: What did the attack mean for the UK and Russia?

- Published

Sergei Skripal, 66, and his daughter Yulia, 33, were found unconscious but both survived the attack

On 4 March 2018 emergency services received a phone call from members of the public in Salisbury who had seen an old man and a young woman ill on a bench. It was a call that would set in motion a chain of events leading to a major crisis with Russia.

After the pair were taken to hospital, local police did an online search on the name of the man taken ill.

The result set off alarm bells. He was a former Russian spy.

A call came into the duty officer at MI6 headquarters that Sunday evening.

The realisation that Sergei Skripal - a man who had provided MI6 with secrets from his time in Russian military intelligence - had been targeted sent shock waves through the building, challenging the very core of its work in recruiting agents to work with the organisation.

Russian spy poisoning: Why was Sergei Skripal attacked?

A few hours later, the next call went to Porton Down, home to Britain's biological and chemical research establishment.

A rapid-response team was quickly deployed. Samples analysed in labs on-site identified A234, a military-grade nerve agent from the Novichok family developed by the Soviet Union in the Cold War.

The revelation caused shock. Detective work by police would identify two officers from Russian military intelligence as the main suspects and a perfume bottle as the means of delivery of the nerve agent onto Mr Skripal's front door handle.

A local woman, Dawn Sturgess would die months later when she came into contact with the Novichok after it had apparently been discarded.

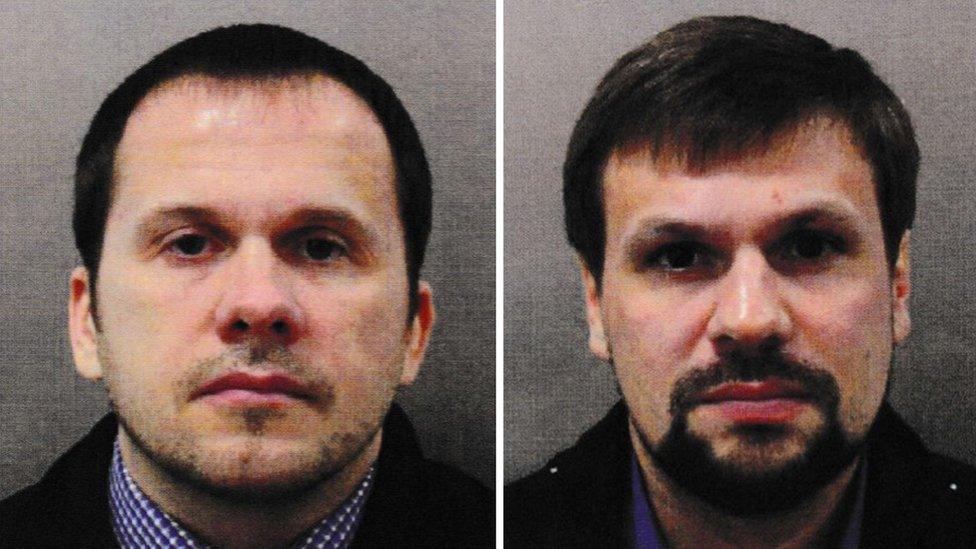

Alexander Mishkin (left) and Anatoliy Chepiga are thought to have carried out the Salisbury attack

Russia denied any role - even putting the two accused men on TV to say they had visited Salisbury simply to see the cathedral spire - but London was convinced it knew who was behind the attack.

When another former Russian intelligence officer, Alexander Litvinenko, was killed in 2006 (that time by radioactive polonium) the response was delayed and perceived as weak.

London was determined to learn its lesson.

An uncertain legacy

Every known Russian intelligence officer operating under diplomatic cover in the UK (apart from the declared liaison officer for each Russian intelligence service) was quickly expelled - 23 in total.

Many other countries then followed suit, with 60 expulsions in the US. It seemed as if the Kremlin was taken by surprise by the strength of the reaction.

But two years on, the legacy of those events looks more uncertain.

British officials believe they did real damage to Russian intelligence operations in the country but that damage is likely to have been short term as new spies were dispatched to replace them and as Russia continues a shift to rely on alternative means of espionage.

In the Cold War, spies under diplomatic cover and illegals were the primary way the Russians could recruit and run agents and steal secrets.

Now there is cyber-espionage and the use of people travelling under different cover, as say businessmen, to operate.

In the wake of the attack, there was also considerable talk of a tougher line over Russian money and influence in London. But there has been relatively little public sign of action.

The failure to publish the parliamentary Intelligence and Security Committee's "Russia Report" about influence and subversion in British life before the election has only added to questions as to whether the appetite to deal with this broader issue remains strong.

There are also cracks in Western unity over a tough line on Russia, with President Emmanuel Macron of France pushing for trying to improve relations with the Kremlin and uncertainty over the position of the Trump administration in Washington.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Russia President Vladimir Putin met during an international summit on Libya in January

Mr Skripal himself has not appeared in public since the poisoning.

MI5 and the Home Office carried out a "refresh" to check on the level of protection for defectors like Mr Skirpal - something officials acknowledge was overdue.

The poisoning itself was a failure, several senior officials who served in British intelligence concede.

A risk assessment was carried out when Mr Skripal was swapped out of a Russian prison in 2010 but the Russia of 2018 was very different from Russia then.

Russia appears to have stepped up a long-standing campaign to track defectors from 2014, including in the US as well as UK.

That was also the point at which relations began to deteriorate rapidly over the crisis in Ukraine and Crimea and in which other alleged operations, like the deployment of online trolls to interfere in US politics increased.

One question western intelligence officials have been asking is whether Russia has been deterred from taking such action again by the Western response.

No one seems sure.

- Published29 March 2018

- Published7 February 2020

- Published6 October 2018