Grenfell Inquiry: Aesthetics v safety v money

- Published

Grenfell Tower before (L) and after refurbishment

Grenfell was the worst residential fire in UK peacetime history, with 72 people losing their lives. We now know what happened - the report on phase one of the public inquiry, external has been published - but the next phase is spending months investigating why it happened, and considering who might be to blame.

Each week, during key sections of the inquiry, we keep you up-to-date with the evidence and what it means.

Week Two: The architects return

It was a three-day week - returning after illness, Bruce Sounes, the project manager from Studio E Architects, external, went sick again on Thursday.

Most of the previous three days had been spent grilling Neil Crawford, the programme manager who took over from him on the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower.

The questioning, by lead counsel to the inquiry Richard Millett QC and Kate Grange QC, is technical, and unrelenting.

As well as pursuing their own lines of inquiry, they interrogate witnesses on behalf of the "core participants", including the bereaved, survivors and residents.

This week, there was a particular focus on what the architects knew about fire safety regulations and what they did to ensure their designs adhered to them.

The cladding was 'horse meat' masquerading as 'beef lasagne', said Mr Crawford

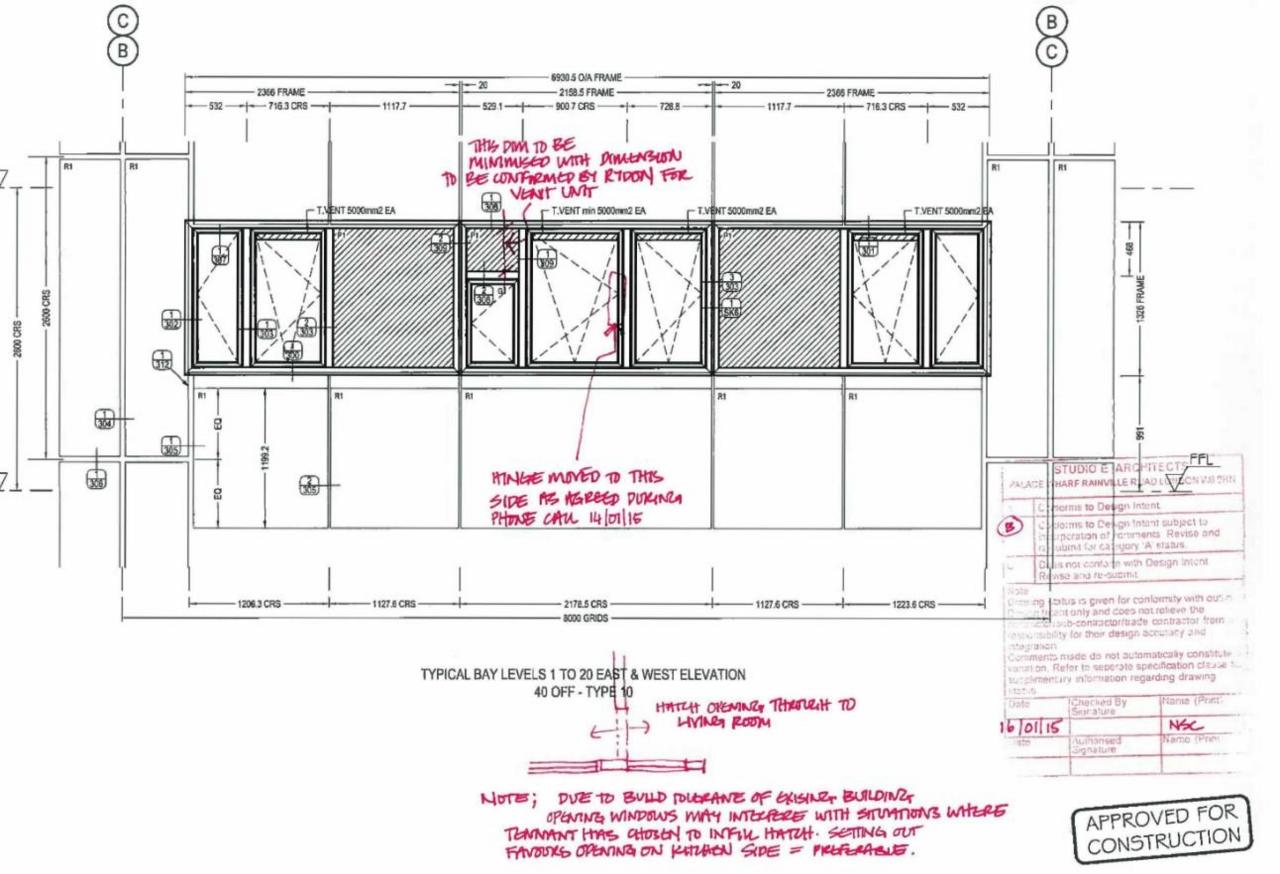

On Tuesday, Neil Crawford was asked about designs for windows he was sent in 2014 and 2015.

He responded: "Architects don't approve drawings, they comment on them."

It was a statement which raises important questions, which the inquiry is clearly thinking about.

A plan of the new window layout with Neil Crawford's notes in red

Was it the job of architects to make safety-critical decisions?

Mr Crawford often suggested that his main concern was the "design intent" or making sure the concept was being delivered.

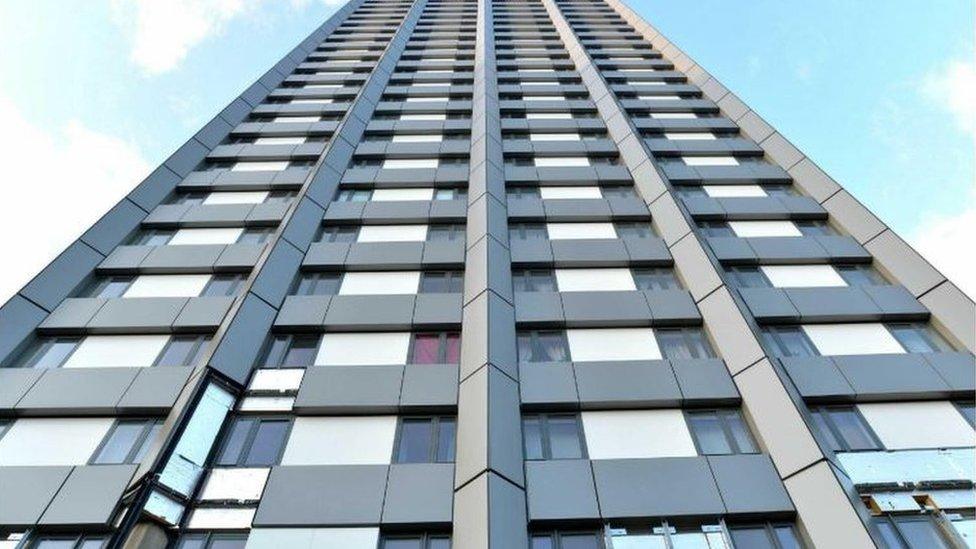

In the case of Grenfell Tower, the concept was to modernise an ageing tower block, improving the layout, making it warmer, and transform its appearance, after all, a gleaming new school and leisure centre were being built next door.

His younger colleague Tomas Rek, who followed him in the witness box, was clear about the priority.

When asked why sleek, zinc cladding had been chosen for the new-look tower, he said: "Based just on the aesthetics."

Architect Tomas Rek gave evidence on Tuesday

It looked better, it was also less likely to burn in a fire - but a third factor got in the way - cost.

Zinc cladding was more expensive and after early pressure to cut the bill, the project decided to switch from zinc to cheaper aluminium in shades of grey.

The panels chosen were the now notorious Reynobond PE ACM, blamed for the rapid spread of the fire.

The inquiry will examine that decision in intense detail.

Should the architects be blamed?

The inquiry will have to decide whether the Studio E Architects should be blamed for focusing on the design rather than the detail of the fire safety regulations.

Some in the business say architects can't possibly understand every twist and turn of the rules, when big projects have specialists for that.

Others say understanding the materials they are using is crucial, especially when it comes to safety.

Tomas Rek was forced to admit this week that he had drafted the National Building Specification for Grenfell Tower using software which inserts pre-written phrases detailing how the fire rules will be adhered to.

That is normal, except, under questioning it became clear he had added combustible insulation to the spec, stating it would meet the guidelines, without checking whether it actually would.

It didn't, the inquiry heard.

"Retrospectively looking at it," he said, "I think it would help if I had a better understanding...

"It's a lesson learned."

Neil Crawford clearly felt he had been misled about the materials used on Grenfell Tower, describing the insulation which contributed to the fire as "horse meat" masquerading as "beef lasagne".

Its manufacturer Celotex, external will tell the inquiry it had successfully tested the insulation panels as part of a specific cladding design, and it was for the architects to use them safely.

Mr Crawford also attacked the official government fire safety guidelines, considered by many in the industry to be so misleading and contradictory that they put lives at risk.

"The building regs aren't fit for purpose and have led to the regularisation of usage of dangerous and flammable materials," he said.

"Unfortunately, the industry only reacts to the regulations that are in place."

Those regulations are so central to what went wrong that the Grenfell Tower Inquiry has allocated them their own "module", due to start later this year.

The aim of the refurbishment was to make it warmer and improve its look

What have we learned from this week's evidence?

A theme is developing in the inquiry as it becomes clear that key decisions fell into the cracks between the companies tasked with redeveloping Grenfell Tower, allowing each to say another was responsible for any failings.

Next week the inquiry expects to hear from Exova, external, the firm of fire consultants which Studio E believed were assessing whether its designs created any risk.

Exova's defence will emphasise that it was left out of the loop, and could not have advised on designs it never saw.