The Uber driver evicted from home and left to die of coronavirus

- Published

The last time Mary Jayaseelan spoke to her husband Rajesh, he was about to be hooked up to a ventilator in a Covid ward.

Rajesh was being treated in Northwick Park Hospital in London, the city where he worked as an Uber driver for most of the year. Mary was 5,000 miles away in their family home in Bangalore, India, with their two young sons. Until that point he had repeatedly told her he would be fine, that he was feeling ill but she was not to worry, he'd get better - at 44 years old, he was young and otherwise healthy.

But on that call, he broke down and admitted: "Mary, I'm feeling a bit scared."

Rajesh Jayaseelan died the following day.

Rajesh and Mary got married on 24 February 2014, and rented a home in Hulimavu, south Bangalore, that they shared with his 66-year-old mum. For most of the year, Rajesh rented a room in Harrow, north London and drove an Uber vehicle in the city. He'd work from late in the evening to the early hours of the morning - the busy hours - so he could save enough money to spend a few months with his family in India.

He enjoyed working as a driver, although he didn't realise that his precarious gig economy job would leave him vulnerable in the global health crisis that would later emerge.

"He'd been living in London on-and-off for 22 years, and would come back to India for a few months at a time," Mary says. "He loved London. He always used to talk to me about how beautiful London was, and so clean. I've never been to London, so he would describe it to me."

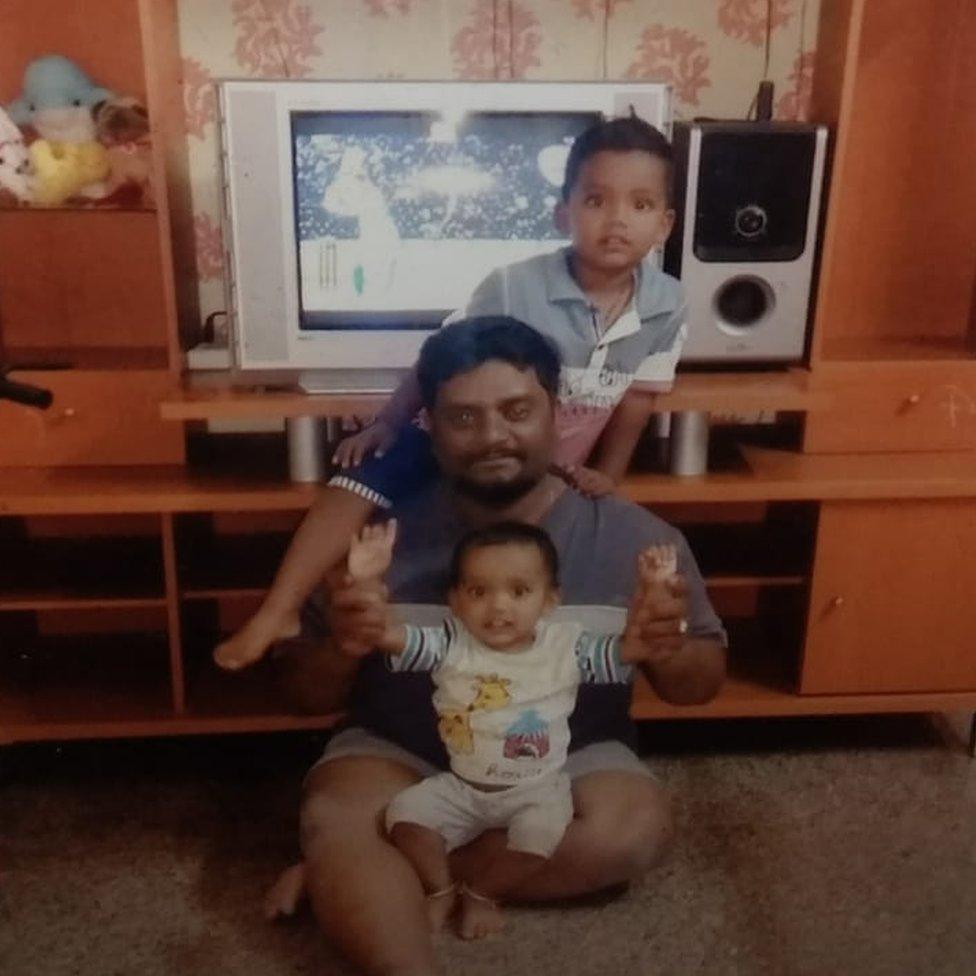

They were very happy. Rajesh loved his wife, and playing with their two sons, aged six and four. When he wasn't in India he would video-call them every day.

"He was also a really good singer," Mary says, full of pride. "He sang a lot of Hindi songs."

He was also a "humble, gentle person" his close friend Sunil Kumar adds. Sunil and Rajesh first met in 2011 - they were both from Bangalore, so mutual friends there put them in touch when Sunil moved to the UK. They would help each other navigate the UK's various bureaucratic systems, loaned each other small amounts of money when needed, and Sunil and his wife would have Rajesh over for meals at their home in Hertfordshire - sending him back with several days' worth of leftovers of delicious South Indian food.

Although Rajesh loved London, he didn't plan to stay forever - he wanted to be reunited with his family in India. Renting their home in Hulimavu was relatively expensive, so during his last stay in Bangalore at the end of 2019, he and his wife took out a loan and bought land to build their own home. The loan was no problem, they thought - Rajesh would go back to London and put enough money aside to pay it off. The next time he travelled to Bangalore, he told his wife, it would be for good.

He came back to London on 15 January. Less than two weeks later, the first cases of coronavirus were reported in the UK.

Rajesh and Mary on their wedding day in February 2014

Although the virus had reached Britain, at this point Rajesh wasn't too worried. Shops and restaurants were still open, people were still going into work and then going out. For everyone, including Uber drivers, it was business as usual, and not much changed for another month.

Then March came around, and the virus was passing from person to person within the UK. The number of cases - and, by now, deaths - was increasing every day. People were told to self-isolate for seven days if they had any symptoms - even mild ones, such as a fever or a persistent cough.

On 23 March, Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced a nationwide lockdown lasting an initial three weeks, meaning that most businesses would close, and people would only be allowed outside for one form of exercise a day and for essential trips to the shops, unless they were considered "essential" workers.

Like many Uber drivers, Rajesh continued to work at first, but he quickly developed flu-like symptoms and had to stop. His last job was on 25 March - a drop-off at Heathrow Airport.

His symptoms became much worse, and he was admitted to the hospital with dehydration. While there, he was tested for the coronavirus.

It came back positive.

Staff told Rajesh to go home, self-isolate, and to come back if his symptoms got worse. He did as he was told, and went home to his room. But things were about to get even worse.

"The landlord sent Rajesh out of the house for something, and when he came back the landlord had changed the locks, so he couldn't get in," Mary says. "He tried knocking on the door and asking the landlord to speak to him, but he wouldn't open the door."

His landlord didn't know about his positive diagnosis - but he told him that, as an Uber driver, he might bring the coronavirus back into the house, and that it wasn't a risk he was willing to take.

With nowhere else to turn, Rajesh was forced to sleep in his car for several nights.

"He had no food in there, nothing to eat at all," Mary says.

At this point he called his friend Sunil for advice.

"That was the last call he made to me," Sunil says. "He didn't go into details about what was happening to him, but because I work in the NHS, he was asking me questions like 'How safe are we', 'Is it better to go to India'… things like that. He was asking me if I knew any routes, if there was any possible way he could go - he wanted to go to India and be with his family. But by that time there was a complete lockdown in India too."

Sunil told him the best thing to do would be to stay at home, not to work, and to look into the financial support for self-employed workers the government had just announced, or the 14 days' assistance offered by Uber.

Rajesh agreed, and explained he needed to find a new place to live because his landlord said he was high risk. But, Sunil says, he didn't say that he'd already been kicked out: "He may have been embarrassed."

Rajesh then went back to trying to call his landlord to plead with him to let him stay. There was no answer.

After days of searching, he eventually found another room in a shared house in Harrow. The new landlord made him pay £4,000 upfront - money he didn't have, and Mary says he had to borrow.

What if this happens to me?

If your landlord kicks you out of your home without giving you notice, or locks you out of your home, it is likely to be an illegal eviction - a criminal offence in all UK nations.

This is still the case during the coronavirus pandemic. Under the Coronavirus Act, notice periods for evictions have been extended to three months.

"This means that for most private and social tenants, even if they receive an eviction notice they're likely to have the legal right to stay in their home," Andy Parnell, helpline adviser for housing charity Shelter, tells the BBC.

But, he says, "sadly there are some groups not protected by the recent changes to the evictions law, including lodgers with live-in landlords".

"Lodgers have fewer rights than private renters with live-out landlords and landlords don't need to go to court to evict a lodger. But they are required to provide reasonable notice before asking them to leave the property."

People in Rajesh's situation should call the local council's homelessness team as soon as possible and all councils have an emergency out-of-hours number. If you don't have anywhere to sleep, you should go to the council's office in person, bringing ID and any proof of immigration status with you.

Earlier this month, Shelter also told renters in this situation to "stay put".

Once Rajesh was back indoors, he didn't want to risk being evicted again. He hid himself away and avoided contact with his new landlord and all the other tenants, not even daring to try and cook a meal for himself. His health became worse with every passing day. The only social interaction he had were daily phone calls with his wife, where he would alternate between reassuring her that he would be fine, and crying.

It was during one of these calls that Mary noticed he was struggling to breathe.

"He was wheezing a lot in that room, and every day it was getting worse," she says. "One night I told him to go to the hospital. He didn't want to call an ambulance because he didn't want others there to know he was ill, in case he was evicted again."

Rajesh drove himself to the hospital, despite being severely out of breath. When he got there he was diagnosed with pneumonia.

"The next morning he called me from the hospital for a video call - but when the children saw him they started crying because of how ill he was," Mary says. "He turned off his video, and told me he didn't want them to remember him looking so unwell." They would speak only a few more times.

On 11 April, the doctors caring for Rajesh called Mary and explained that he was in a critical state, and they didn't think his condition would improve. They arranged a video call for her and the children to see him one final time; he was unconscious. He died two hours later.

While "coronavirus doesn't discriminate" has been repeated often during this pandemic, it is evident that the virus is worse for some than others. One group hit particularly hard are gig economy workers.

The gig economy is where people take on short-term or freelance work instead of permanent jobs. These include private-hire cab drivers like Rajesh as well as food delivery workers and couriers. Last year about 4.7 million people in the UK worked in gig economy jobs while, according to a 2018 study, 60% of the global population, external is in insecure work.

Research by the World Economic Forum and other bodies shows these workers are disproportionately affected by the pandemic - a combination of being classified as "essential" workers, requiring them to continue interacting with strangers; a lack of guaranteed paid sick leave that makes it harder to self-isolate; low and insecure pay, making it more likely for them to be living in dangerous and insecure housing situations; and no entitlement to risk assessments or protective equipment.

Ayako Ebata, from the Institute of Development Studies, says because people in insecure work "heavily rely on their daily wages", they are under a lot of pressure not to lose their jobs or take time off, even when there are significant health risks.

"It's not because they're ignorant or uninformed, it's because the whole system is forcing them to make decisions that eventually prove detrimental to their livelihoods and health," she says.

Dr Alex Wood, a sociologist at Oxford University focusing on the gig economy and insecure work, agrees - and says a lack of workplace protection makes the problem much worse.

"People have been told by these platforms that they don't need to worry about [rights and protections] because when the economy's fine, there isn't really any risk," he says. "In reality, when you have these crises, it's the workers who pay - despite many of them now being classified as 'essential'."

Now, drivers in the UK are calling for greater protection from the government. United Private Hire Drivers (UPHD), an independent trade body for private-hire drivers, has this week called for an urgent judicial review on the matter.

"What the government is saying now is that it's not safe for you to go to a barbershop, but it's somehow safe for you to ride around in an Uber," James Farrar from the UPHD says.

Race is a risk factor, too. According to multiple recent studies, BAME people in the UK like Rajesh are disproportionately more likely to be in insecure work than their white counterparts.

Research from the Trade Union Congress (TUC) last year found that ethnic minority workers are a third more likely to be in insecure work. A report released last month by Carnegie UK Trust, UCL and Operation Black Vote also found that BAME millennials in particular were 47% more likely to be on "zero-hours" contracts - another notoriously unstable form of work.

At the same time, recent studies show that BAME people in the UK are disproportionately more likely to become critically ill and to die from coronavirus. Ethnic minority patients make up 34% of those in intensive care, despite making up only 13% of the population.

Early research suggests this is down to a combination of risk factors - an increased incidence of high-risk underlying health conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension, as well as social factors and systemic inequality.

"Coronavirus is making a lot of the inequalities in our society that we had previously turned a blind eye to, very clear," Dr Wood says.

After learning that her son had died, Rajesh's mother became ill. She suffered hypertension and a spike in her blood sugar level, and has been confined to her bed. "She's been inconsolable since," Mary says.

Faced with a loan for the house, upcoming medical bills and children's school fees, Mary is trying to find work as a cleaner in their area but the lockdown is making it much more difficult to get on top of their finances.

Sunil is helping them with money where he can, and has set up an online fundraiser for them, external. He's also looking into whether he can pursue legal action against Rajesh's first landlord, and Mary's relatives in Bangalore have set up a fundraiser for her in India. Uber also contacted the BBC to offer their condolences.

But more than anything, Mary is struggling to come to terms with how quickly everything has changed for her family.

"Now that Rajesh is gone, our life has become very difficult," she says. "I don't know what we'll do without him."

- Published7 April 2020

- Published24 March 2020

- Published23 April 2020