Coronavirus: Archbishop Justin Welby says austerity would be catastrophic

- Published

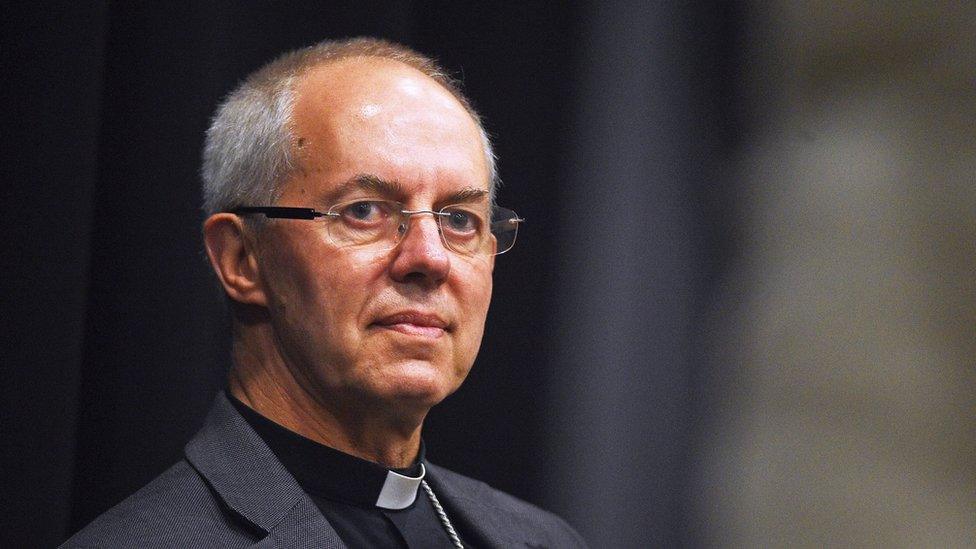

The Archbishop of Canterbury has warned cuts to public spending after coronavirus "would be catastrophic".

The Most Reverend Justin Welby called for politicians to be "brave and courageous" as they sought to deal with the economic and social consequences of the lockdown.

In response to spiralling public debt he said "going for austerity again would be the most terrible mistake".

Estimates suggest the crisis could cost up to £298bn for this financial year.

The Office for Budget Responsibility which keeps tabs on government spending, made the estimate for the figure for the final bill, for April 2020 to April 2021.

The prime minister reportedly told backbench Conservative MPs on Friday there was "no question" of cutting public sector pay.

Boris Johnson has previously insisted the costs of the crisis would not mean a fresh round of austerity, saying: "That will certainly not be part of our approach."

Mr Welby, who worked as an oil executive before being ordained, was speaking to the BBC ahead of Mental Health Awareness Week.

He called on government ministers to invest in mental health services and for a royal commission to be set up on social care.

"Borrowing costs are the lowest they've ever been in our entire history. Spending money on mental health will have a positive rate of return," he said.

"We can do it now in a way we've never been able to [before]. We must be brave and courageous in setting our vision for what society will be."

He went on: "Just because we're in the middle of a crisis, it doesn't mean that we can't have a vision for a future where justice and righteousness are the key stones of our common life.

"So we fund mental health; we have a commission of inquiry into what we learn from this - not to blame, but to learn; we have a royal commission on how we look after social care."

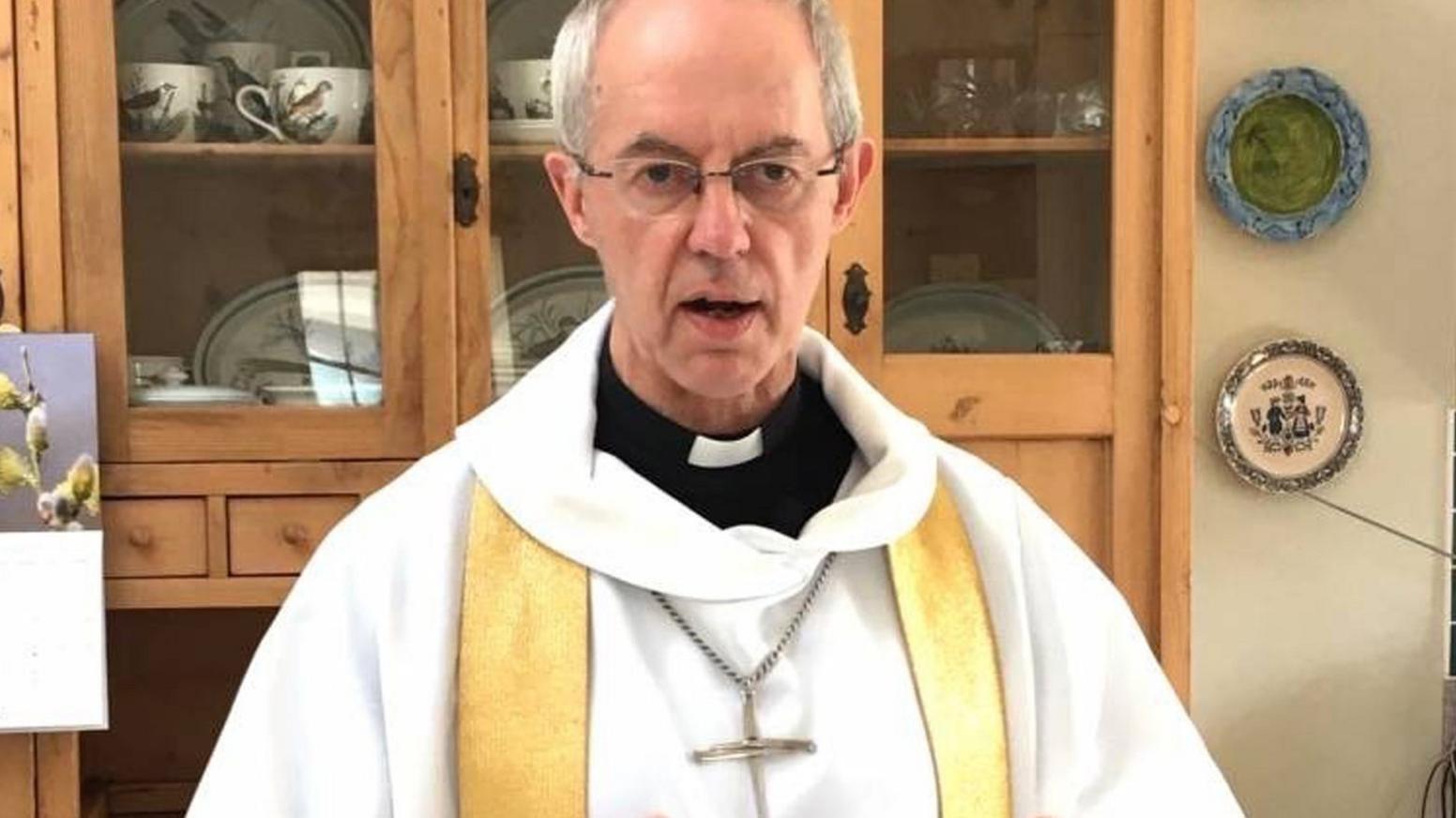

The BBC's Andrew Marr asked the archbishop what it was like to deliver an Easter sermon from his kitchen

Mr Welby has spoken openly of his own mental health struggles. He revealed he was suffering from depression last year in a Thought for the Day broadcast on BBC Radio 4's Today programme and separately said he was taking anti-depressants.

Speaking this week to the BBC's religion editor Martin Bashir, he described "an overwhelming sense the world is getting more and more difficult and gloomy".

Explaining how his own mental health has affected his behaviour, he said: "You turn inwards on yourself a lot. You become, frankly, narcissistic. And when you have good friends or family who spot it, they can say 'might it not be an idea to talk to someone'. Which I did."

He added: "There is nothing pathetic about it. It is no more pathetic than being ill in any other way. And we just need to get over that."

RISK AT WORK: How exposed is your job?

SCHOOLS: When will children be returning?

EXERCISE: What are the guidelines on getting out?

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

Both the archbishop's parents were alcoholics and he said his childhood was "disturbing" and "chaotic". Later, while working in business, his seven-month-old daughter Johanna died in a car crash.

"As we will see as the recession takes hold, loss, grief, and anxiety are traumas. And trauma has to be gone through. You can't do it just with the stiff upper lip."

He said the whole country had been "compulsorily fasting" and that had caused "huge suffering" for many.

Asked what how he hoped Britain would recover after the coronavirus crisis, he said: "We don't do it with austerity. We don't do it with class fighting. We do it with community and the common good. And we're not afraid of spending money that will produce a better society."

The archbishop has chosen to repeat a theme that runs through his book "Dethroning Mammon" published four years ago: that wealth is not an idol to be worshipped but an asset to be deployed for the benefit of all people.

He's likely to enrage some politicians who will dismiss his remarks as irresponsible and failing to acknowledge the damaging effect of large deficits.

But he does have particular insights into the impact of austerity - with the Church of England educating one in five primary school children, running vast numbers of food banks and engaged in a range of social projects that seek to support the young and the old in deprived and disadvantaged areas of the country.

It is why he believes the burden of rebuilding post-pandemic Britain must not "fall upon the shoulders of those who are already turning up at food banks".

- Published12 April 2020

- Published14 May 2020

- Published22 June 2021