Coronavirus: Who are the contact tracers and what are they doing?

- Published

Many tracers are working from home as they try to find people who may have been exposed to the virus

Health Secretary Matt Hancock told the 25,000 contact tracers they are the "key to unlocking the lockdown" in England. But who are the people making the calls and what is the job like?

Some of them are trained medical professionals, doctors and nurses taking a break from their usual career to join the fight against coronavirus in a different way.

Others were recruited from call centres or they are students looking for a summer job.

From Thursday, their task is to help discover who may have been in contact with a person who has tested positive for coronavirus.

Many people who test positive will fill out an online form listing who they live with - the contacts who are most at risk - along with any they have been in close contact with (defined as within two metres for 15 minutes).

Others, perhaps because they struggle with the technology, will get a call from someone like Lucy. (Contact tracers have been asked not to talk to the media, so names have been changed.)

A student in biomedical science at a university in the south of England, she applied for what was advertised as a customer service job before learning that she would be working on coronavirus contact tracing.

Lucy says the idea of helping people appealed to her but adds: "Honestly, I needed the money." With her usual summer job in a pub out of the question, contact tracing was a rare opportunity.

She says she was hired the day after a "very informal" phone interview where she was asked about her customer service experience and the specification of her laptop - contact tracers are often working from home and some of them are using their own computers.

Tracers will work through a script on the call, asking people about who lives with them, when their symptoms started and whether they had been anywhere in the two days before they felt ill.

They may use cues to try and jog the memories of the more forgetful, asking people to check diaries, or reminding them of what the weather was like on the days in question.

'No room for mistakes'

Lucy says if someone can't talk right then, they are directed to push a button and queue that person up for a call from another tracer later. They're also given a script to deal with family members sensitively if a person they are calling has died.

"I feel very prepared for it," says Lucy, although she adds that the weeks before launch were sometimes confusing. "We'd get one lot of information and then the next day, it'd be, 'oh sorry, that's changed now'."

Imran, from Lancashire, was hired on a temporary contract for NHS 111, but when the call volume dropped as coronavirus cases fell, he was moved onto the test and trace system.

He felt confident about the scripts and information they had for 111 but says they were "thrown into deep water" with contact tracing, having had no access to key systems before the launch and some "very basic" training.

"The way the scheme has started on the wrong foot, I think many people won't take this advice. I don't think they're going to adhere to it," he says.

"I don't think there's any room for making any more mistakes. If this doesn't work it's going to cause a lot of issues."

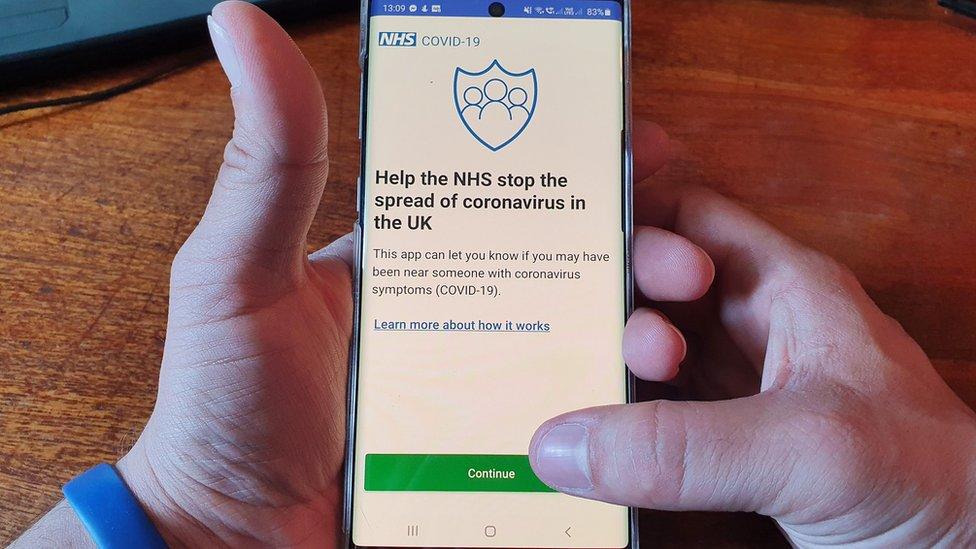

A mobile phone app to help tracers reach hard-to-find contacts has not yet been widely released

Some staff with specialist expertise are given supervisory roles, dealing with more complex cases where a contact cannot easily be found or someone is not sure of their movements.

Harold, who usually works as a locum A&E doctor and is now a team leader on the test and trace system, says he felt the launch was "rushed through" after waiting several hours on Thursday morning unable to log into the systems.

Originally he had been told it would launch on 18 May, until it was cancelled the day before. He only found out it was starting on Thursday when it was announced live on TV.

Harold says he is "not hugely optimistic" the public would comply and self-isolate when they get a call from a contact tracer.

"It's difficult when you see people breaking rules," he says. "Everyone is confused what the message is."

SCHOOLS: When will children be returning?

EXERCISE: What are the guidelines on getting out?

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

RECOVERY: How long does it take to get better?

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

But if someone like Harold has an issue he can't resolve, he can call on support from Public Health England (PHE).

Trish Mannes, who leads contact tracing for PHE in the South East, says they learned during the early stages of the outbreak that the important skills for tracers were empathy, rapport and an eye for detail.

"It's a bit like detective work, trying to work out exactly where people have been," she says.

Despite concerns about privacy, asking people about their contacts is a routine public health measure for infectious diseases, she says. "We collect this all the time, People are generally very willing to provide it."

Thursday's launch may have experienced a "technical glitch", Ms Mannes says, but calls were going out from 09:00.

She says the test and trace system would be "fully operational" by 1 June - currently it is missing the mobile phone app which is intended to find contacts the infected person may not even know.

"I think this will work," says Ms Mannes. "We've recruited enormous numbers of people to help with this. We've never done it on this scale before - but we're used to doing it in small doses."

- Published5 August 2021

- Published23 May 2020

- Published5 May 2020