Coronavirus: What is the future of religious worship in the UK?

- Published

In Northern Ireland, places of worship have recently started opening for solitary prayer, with safety measures in place

For almost two months, religious groups have been unable to attend their normal places of worship, as mosques, churches, synagogues and temples remain shut under government coronavirus rules.

Communities Secretary Robert Jenrick warned at Sunday's No 10 briefing that "large gatherings in places of worship, particularly because of the demographic in some faiths, because of singing hymns and so on - which can lead to exhalation - can create particular problems."

And the government's scientific advisers say some form of social distancing is likely to be in place for many months to come.

So what is the future of religious worship in the UK with ongoing social distancing?

'Deep spiritual sacrifice'

As faith leaders consider a return to their religious buildings, some fear their returning communities will be traumatised by the ban on communal worship.

"Emotionally we will be broken, without a shadow of a doubt," says Sheikh Nuru Mohammed, one of the UK's most senior imams, who is planning his return to the KSIMC Shi'ite mosque in Birmingham.

In many religious communities, there is a theological requirement that certain rituals are performed communally.

Sheikh Muhammed says Friday prayers - the most significant of the week for both Sunni and Shia Muslims - can only fully take place communally in the mosque.

Meanwhile in Catholicism, the Mass is central to worship and involves the physical consumption of bread and wine.

Cardinal Vincent Nichols, the most senior Catholic in England and Wales, has spoken of the "pain" and "deep spiritual sacrifice being made" in withholding Holy Communion.

As part of Northern Ireland's five-stage plan to ease its lockdown, drive-in church services can now be held and churches can open for private prayer with appropriate social distancing.

Faith traditions 'flexible'

Dr Mehrunisha Suleman, an Islamic academic at the University of Cambridge, says Muslim tradition and teaching allow for changes to be made.

Events such as Friday prayers or Eid prayers to mark end of Ramadan were permitted at home this year when normally they could only be said in a mosque

"There's a lot of flexibility within the theological, the ethical and the legal tradition, about being able to adapt practices to be able to accommodate for circumstances like this," she says.

The suggestion of flexibility to allow traditional religious practices to change and adapt to new coronavirus regulations is being seen in other faiths as well.

Tilak Parekh, an academic and expert in Hindu theology, says he is seeing an increasing amount of innovation in how traditional ceremonies are allowed to happen.

The BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir in north-west London

The BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, commonly known as the "Neasden Temple", in north-west London, is enabling families to carry out the funeral rituals at home which were traditionally done by a swami, or priest, with a large crowd attending.

"All of a sudden now we see concessions, we see adaptations, we see innovations," he says. "If one was to suggest this a year ago there would have been protests; 'Oh no, this is how we've always done it. This is the traditional way.'

"People have changed the way they practise."

Across different faiths, religious leaders are exploring the implications of having to change long-held beliefs and practices.

Singing ban

Communal singing is a common aspect of worship across religions, particularly in Christian denominations.

But as churches in Germany have reopened with social distancing, singing remains banned due to the fear it could cause infected droplets from people's mouths to remain in the air for longer and travel further.

The Rt Rev Sarah Mullally, Bishop of London, is leading Church of England planning on how to reopen its buildings after lockdown.

"Our future is going to be very different for a very long time," she says. "There are some very challenging questions that we will have to face, not least about singing and about receiving Holy Communion."

Pilgrims pray in the courtyard of the Prophet Mohammed Mosque in the holy Saudi city of Medina

And what about the Islamic pilgrimage - Hajj - which is due to take place in the summer?

Typically more than two million pilgrims attend the rituals, which are spread over five days in and around Makkah, the main holy city in Saudi Arabia.

There are several aspects of Hajj that public health experts worry could cause a surge in infections.

For example, the mosque in Makkah as well as Hajj sites in Mina, Muzdalifah and Arafat, have shared washing facilities so pilgrims can prepare for prayer.

Social distancing would be impossible, experts warn, unless there was a drastic reduction in numbers.

Muslim pilgrims perform the circumambulation of the Kaba in the holy city of Mecca, Saudi Arabia

Similarly, pilgrims are banned from covering their face or head during the prayers, making face masks impossible unless there is an edict to change Islamic law.

Dr Suleman warns that, if Saudi Arabia reduces the numbers allowed to attend Hajj, there will be long-term implications for Muslims' ability to fulfil their pilgrimage duties, especially those who have waited a long time to go or who might struggle to afford it allowing fewer people to go made the Hajj more expensive.

She adds that Islamic scholars will be exploring ways to adapt Hajj requirements to allow for stricter public health measures.

Silver linings

Despite the sadness and widespread concern, there are some positives for religious communities.

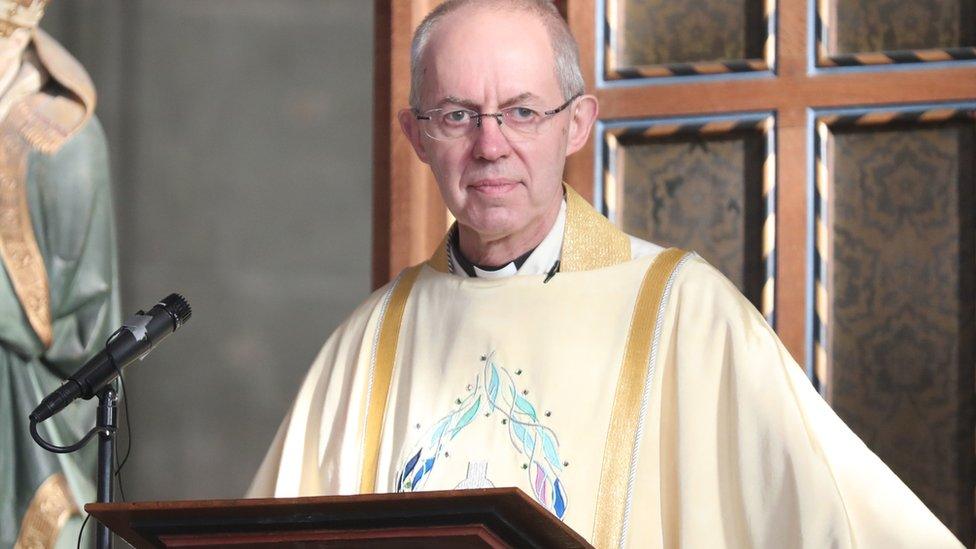

The Rt Rev Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, said the virus offered an opportunity to address inequalities in society.

"Just because we're in the middle of a crisis, it doesn't mean that we can't have a vision for a future where justice and righteousness are the keystones of our common life," he said.

"We can do it now in a way we've never been able to [before]. We must be brave and courageous in setting our vision for what society will be."

- Published10 May 2020

- Published8 April 2020

- Published22 May 2020