Black Lives Matter: Talking about racism 'my job as a parent'

- Published

Denis Adide is raising his three mixed heritage children in a diverse area of London

Support for the Black Lives Matter movement has swelled across the UK since the killing of George Floyd, but the focus has left many parents struggling to know how best to explain racism to their children.

"Why does it need to say that?" was the question Denis Adide's five-year-old daughter asked when she spotted a Black Lives Matter banner.

"This is the reality for a black child, this is the reality for me as a black father," Denis says. "You don't get the luxury of childhood innocence for as long as other people do."

"I know there are children engaging with black history for the first time in their lives," he says.

He says that while his three children, all under five, are too young to have a direct discussion about George Floyd, he knows many other black children have been affected by it.

He cites his friend's daughter, who was left in tears, wondering whether she was unsafe because of her skin and whether or not she should be worried for her life.

"It's an awakening perhaps, for the children - but unfortunately a stressful one, really deeply stressful, because it's a bodily experience. You can't disembody yourself to escape it."

Denis, from west London, says equipping his kids for what it's like to grow up in the UK with darker skin is part of his job as a parent.

He says he has been stopped and searched many times by the police, both as an adult and a child, and says he will "sadly" have to prepare his four-year-old son for the same treatment.

He expects different conversations to crop up with his daughters, particularly around body image because of a lack of representation in society.

His eldest daughter was "thrilled", he says, when she was taught one day by a gymnastics teacher at school who was also mixed heritage. She told her father, unprompted, "the teacher today had hair like mine, and skin that looked like mine".

Georgena Clarke's daughter wanted to know why she didn't have blonde hair like the princess in Frozen

Georgena Clarke from Cheshire says she's faced similar conversations with her seven-year-old twins - a girl and a boy.

The issue of skin colour was first raised by her daughter. She says the lack of diversity in her local area led to her daughter going through a phase of waving to every black person on the street because "she saw them so rarely, she thought everyone who was black was related to us".

She was the only black child in her class and one day, age five, she refused to get out of the car when they got to school, saying "mummy, I don't want to be the only one that's different".

"I was absolutely floored," says Georgena. "I didn't know what to say in that moment in time, and I knew then that I hadn't done a good enough job.

"I'd previously said 'it's because you're special, you're the only one who's brown and you're just different from everybody else', but that wasn't good enough for her now."

Georgena explained to her daughter that her mummy's parents were African and her daddy's parents were from the West Indies, and everyone in those countries "looks like us". She used YouTube videos to prove it.

"I've never seen someone grab a concept so much to the point where everyone she then met afterwards, she had to tell them where she was from. She was really proud of it."

Georgena says she accepts their innocence will have to come "to a crashing end at some point", but she wants them to stay children for as long as possible.

"I want them to be proud of the fact they're black, and also not to feel that their difference is viewed negatively," she says.

"If I tell them about racism, and bring into their world the fact that some people won't like them because of their difference, that could affect their self esteem."

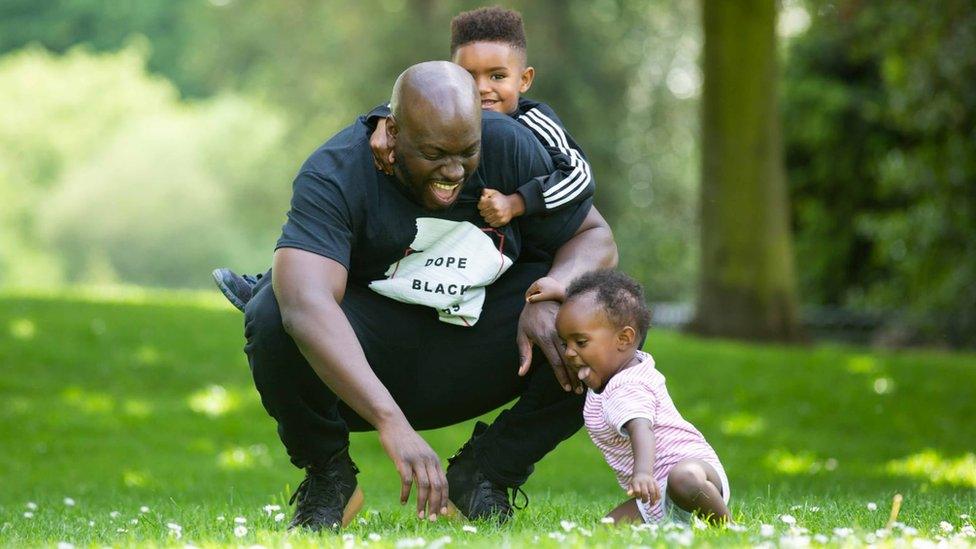

Marvyn Harrison has a four-year-old son and two-year-old daughter

In Hackney, east London, father-of-two Marvyn Harrison, is worried about how his four-year-old son will be perceived when he starts school in the autumn.

"My son is very confident. This is a big challenge for a black male. My understanding of what confidence looks like to someone who isn't black, is it can look like it's intimidating, it's overbearing, or it's disobedient."

He says he's trying to teach his son a different code of behaviour for when he starts his new school. They walk past it every day, pausing for a few minutes as he tries to reinforce the message to his son.

'I love my hair, I love my skin'

Marvyn, who founded the Dope Black Dads online group, was scarred by his own experience of school, where he felt his skin colour meant he was singled out unfairly by teachers, as well as being given a message to have lower life aspirations.

"Quite often what happens with black children is that they start to question 'why am I being treated differently - I feel like I talk as much as Sue who sits next to me but I'm somehow in more trouble'. Then you start living in your head and you start shrinking in school."

He is determined not to let his children view being black as something negative and has taught his son to do daily positive affirmations.

"He looks in the mirror and says 'I love my hair, I love my skin, I love my jumping, my running, I'm kind'. He says all those things every day so that's what's in his head if he is ever challenged."

"It's important to prepare them as early as possible - just do it at the level they can understand."

How to talk to children about racism

Unicef,, external the United Nations children's agency, gives this advice:

Under five years old:

Use language that's age-appropriate and easy for them to understand. Recognise and celebrate differences

Be open - make it clear you are open to your children's questions. If they point out people who look different avoid shushing them or they will start to believe that it's a taboo topic

Use fairness - it's a concept those around five tend to understand quite well. Talk about racism as unfair

Six to 11 years old:

They are also becoming more exposed to information they may find hard to process. Be curious. Listening and asking questions is the first step

Discuss the media together - social media and the internet may be one of your children's main sources of information

Talk openly - having honest and open discussions about racism, diversity and inclusivity builds trust. It encourages them to come to you with questions and worries

12+ years:

Teenagers are able to understand abstract concepts more clearly and express their views. Find out what they know. What have they heard on the news, at school, from friends?

Ask questions about what they think about things such as news events and introduce different perspectives to help expand their understanding

Encourage action

George Floyd: Newsround special programme on US protests and racism

Read more here from CBBC.