Fergal Keane: My family and the empire's complex legacy

- Published

My people fought the British Empire and they defended it.

Some battled British soldiers in rural Kerry and on the streets of Cork city. A generation earlier, others wore the uniform of the imperial police.

Colonialism can throw up complex allegiances.

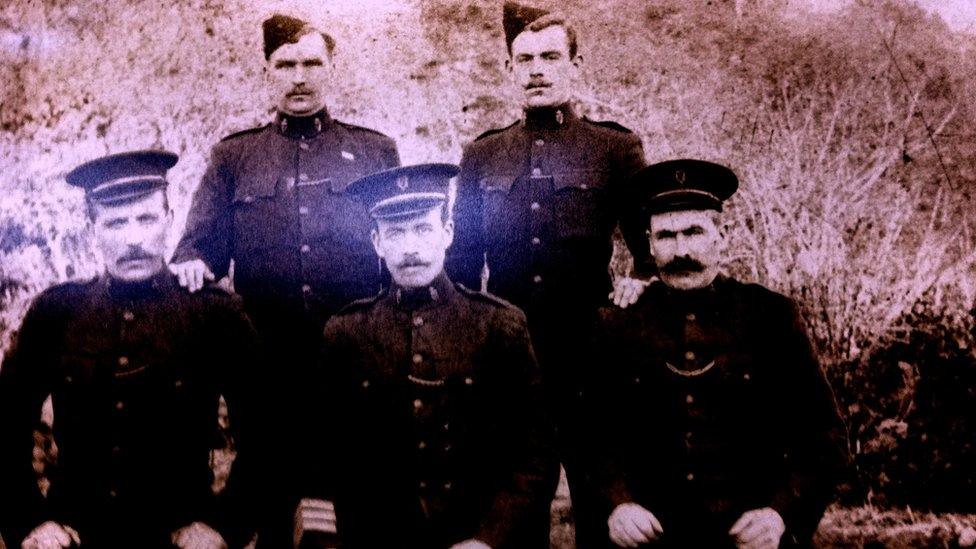

I had a great-grandfather who served as a sergeant in the Royal Irish Constabulary. His son - my grandfather, Patrick - joined the IRA to drive the British out of Ireland.

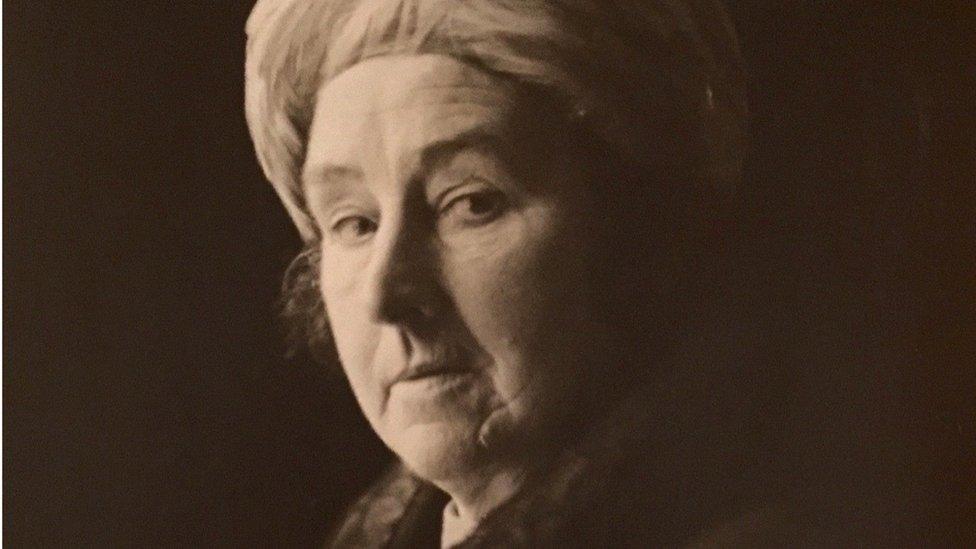

My paternal grandmother, Hanna Keane, gathered intelligence for the IRA and received a death threat from the Black and Tans - the police reserve notorious for its brutality during Ireland's revolutionary war.

But when 26 of Ireland's 32 counties became independent in 1922, Hanna supported the new state in a war against old IRA comrades who refused peace with the British Empire.

Empire and its legacies have been much on my mind in recent weeks. The protests launched by the Black Lives Matter movement are prompting calls for a complete re-evaluation of British imperial history.

My life and the lives of my forebears were shaped by the historic links with Britain.

At the end of the 19th Century, when my great-grandfather, Sgt Patrick Hassett Sr, was patrolling in Cork, the British Empire was the most powerful the world had ever seen. It covered roughly 20% of the Earth's land mass and ruled over 20% of the world's population.

My great-grandfather, Patrick Hassett (centre) served as a sergeant in the Royal Irish Constabulary

He could not have imagined the end of empire in Ireland. "Cork in those days was a very loyal city," as my mother often told me.

He was a serving officer when Queen Victoria visited Ireland in April 1900. There was noisy protest on the part of militant nationalists, but newspapers reported on the "endless streets full of enthusiastic people" and the "Children's Treat" - a picnic for 52,000 youngsters in Dublin's Phoenix Park.

Ireland seemed settled within the Empire. The great issues of land and religion had been resolved in the previous century. Home rule for the Irish - within the Empire - was the political goal of mainstream nationalists.

Yet a few days into the royal visit, there were reminders that all was not well in the British Empire.

Far away in South Africa, Boer forces defeated the Royal Irish Rifles at the battle of Reddersberg in the Orange Free State. The British would win the war but the Boer defiance inspired Irish nationalists.

A senior civil servant in Dublin warned that the Boers had created "this idea amongst the younger men of getting the possession of arms".

Queen Victoria in Dublin's Phoenix Park during her state visit to Ireland in 1900

They got the guns, and in 1916 launched a revolution which - just six years later - ended British rule in what became the Irish Free State, precursor to today's Republic.

The Irish revolution inspired anti-imperialists across the world, from Jawaharlal Nehru in India to Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam.

As a child, I was taught to be proud of the revolutionary part of my Irish past. The very real history of massacre and dispossession was stressed.

But the imperial connections of so many Irish families were rarely if ever mentioned. Many thousands had ancestors who enforced the imperial writ as soldiers or civil servants across the world. Empire gave Irish Catholics opportunities they were denied at home in Ireland, where sectarian pressure often meant the most senior jobs were reserved for Protestants.

It was an Irish Catholic governor, Sir Michael O'Dwyer, who imposed martial law in Punjab, and supported the actions of his subordinate Col Reginald Dyer after hundreds of Sikh civilians were massacred at Amritsar in 1919.

Such deep imperial connections ran contrary to the pure nationalist narrative that prevailed in my childhood.

By the time I was old enough to appreciate my physical surroundings, almost all of the imperial monuments had disappeared in Dublin. The most prominent was Nelson's Pillar - blown up by the IRA in 1966, when I was just five years old.

A 19th Century photograph taken in Dublin, with Nelson's Pillar in the background

These days there is more room for the nuances of history in the Republic. The embrace of the European project has helped Ireland become psychologically independent. The end of the violence in the north of Ireland has made it easier to examine the past in all of its complexity. History is much less of a weapon these days.

When Sinn Fein made dramatic electoral gains at the last election in the south, it was down to economic and social problems, not any resurgent animosity towards Britain.

Yet history can sometimes ambush the present. When the UK Home Secretary Priti Patel suggested that the prospect of food shortages could be "pressed home" to pressure Dublin in Brexit negotiations, the horrors of the 19th Century Great Famine were recalled. A former Irish ambassador to London, Bobby McDonogh, said Ms Patel had displayed "a breathtaking ignorance of history".

Examining the imperial past demands humility and a willingness to face sometimes uncomfortable truths. Education is critical to this process.

I went back recently to my ancestral town of Listowel in north Kerry where my grandmother, Hanna, had been part of the deadly war against Britain a century ago.

My grandmother, Hanna Keane, gathered intelligence for the IRA

There are no statues there from the imperial era. But nor are there any to celebrate dead revolutionaries. Instead, writers and social reformers are commemorated in stone and bronze.

Sitting in front of Listowel Castle, where the English hanged the Irish garrison in 1600, I met a group of history students from Presentation Convent school. Nearly a century after the end of British rule, the past is still present in their lives: in the language that they speak, in the systems of law and government under which they live, and in the lingering divisions in the north of the island.

Yet this generation is avowedly outward-looking.

They have been taught history that embraces complexity, not a simple narrative of heroes and villains. There is a self-confidence that comes from growing up in a stable modernising democracy, no sense of being "less than" the big island next door.

As 18-year-old Mary-Kate Reidy put it to me: "I think we're certainly equal in this day and age. Like, we've definitely come on a lot - British and Irish relations… We are equal pegging now".

It is not a world my forebears - on either side of the imperial divide - could have imagined over a century ago.

But, leaving Listowel, I remembered James Joyce's line from Ulysses about history being "a nightmare from which I am trying to awake".

The past is no longer a gaping wound. It really is the past.

Read more stories about the legacies of British colonial rule and how it is still affecting people today:

- Published6 July 2020

- Published6 July 2020

- Published3 July 2020