Eat Out to Help Out drives UK inflation to five-year low

- Published

- comments

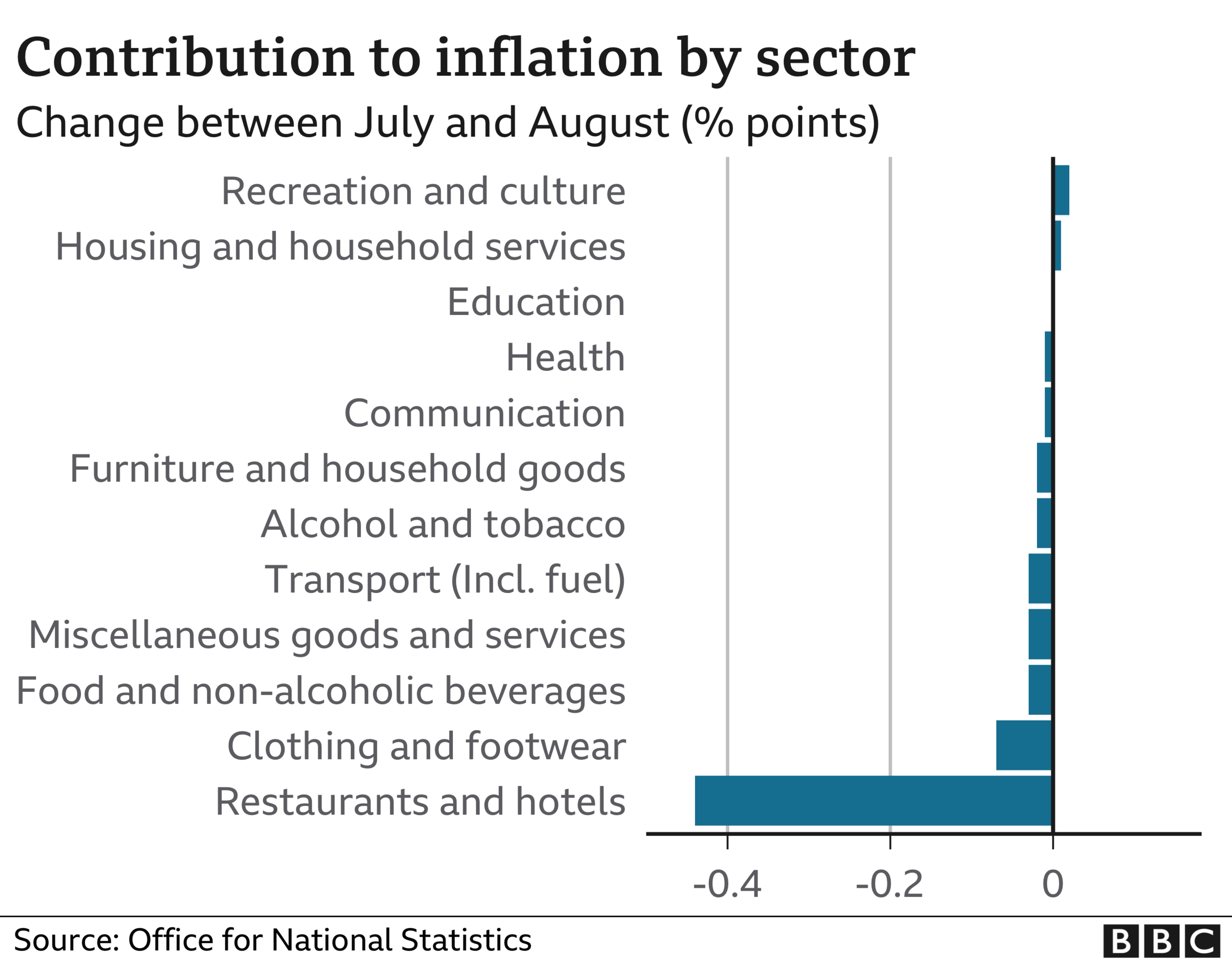

Cheaper restaurant meals due to the Eat Out to Help Out scheme saw prices rise at their slowest rate in five years.

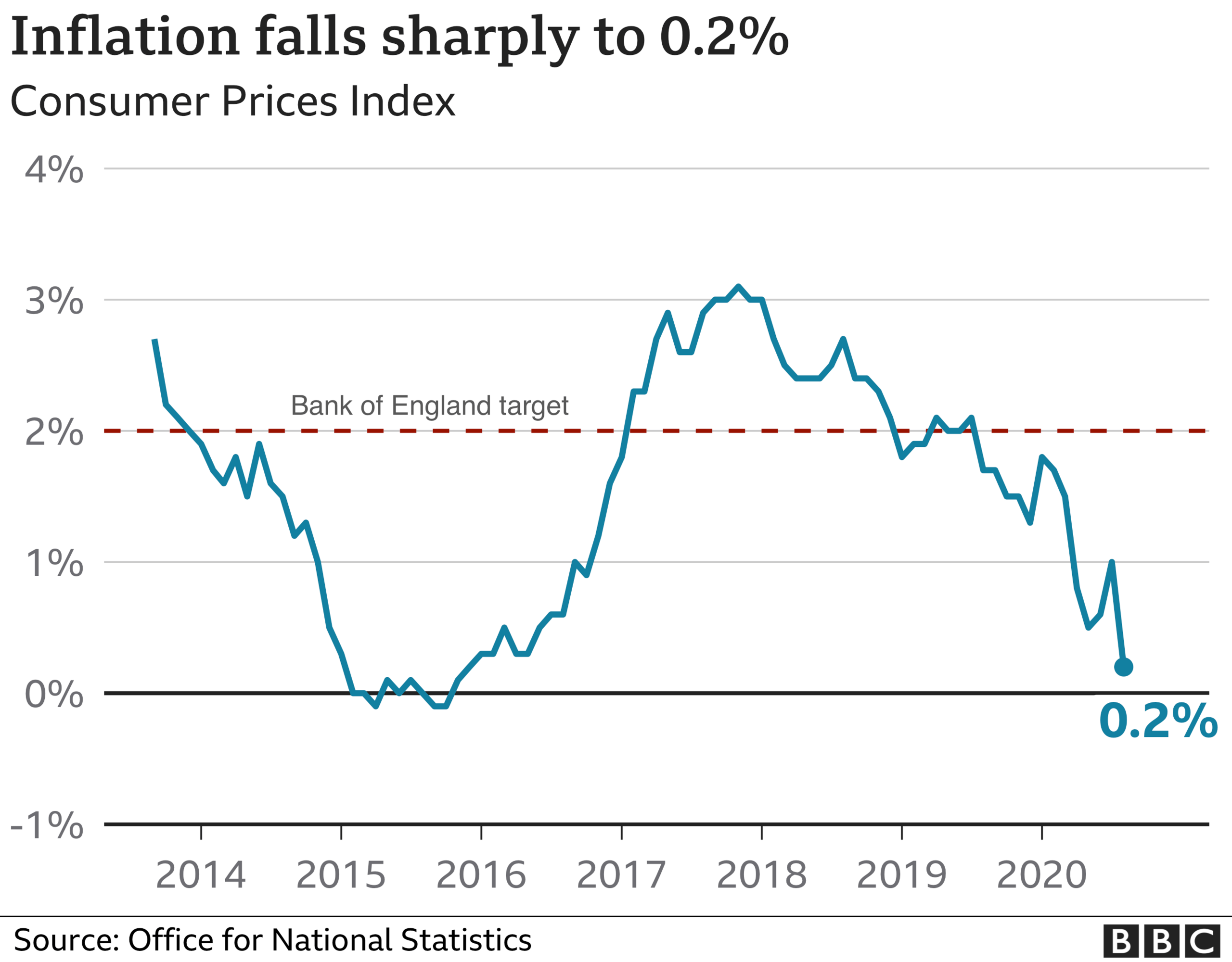

The UK's inflation rate, external, which tracks the prices of goods and services, fell to 0.2% in August, from 1% in July.

Low inflation - the rate at which prices of everyday goods and services rise - is good for consumers and borrowers, but can be bad for savers.

That is because while it makes things cheaper, it also affects the interest rates set by banks and other firms.

The eating out scheme, which ran from Monday to Wednesday in August, offered 50% off food up to the value of £10.

Discounts for more than 100 million meals were claimed through the scheme.

Prices in restaurants and cafes were 2.6% lower than in August last year, the first time they had been negative since records began in 1989, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said.

The cut to the rate of value added tax (VAT) also helped drive prices lower, it added.

The discount, from 20% to 5%, lasts until 12 January next year, was introduced on food and non-alcoholic drinks as well as accommodation and admission to attractions across the UK.

Restaurateur Paul Sharma

What difference did all that make to restaurant owners?

Paul Sharma, owner of the newly established 2020 World Buffet restaurant in Peterborough, is extremely grateful to the government for the Eat Out to Help Out scheme.

He first opened his doors to customers on 16 March, just before lockdown, but after a mere four days, he had to shut up shop.

When he reopened, he had to reduce the restaurant's capacity of 450 to just 170 to follow social distancing measures, but he was fully booked and able to seat 1,000 people a day by opening right through the day.

"We had many, many thousands of customers," he told the BBC, adding that the Eat Out to Help Out scheme was "massively helpful".

"It's one of the best things the government has done for small businesses," he said.

"We could pay the salaries of our staff, we could pay all the outstanding bills that were pending since March.

"We're going to survive for the next few months and then hopefully, in the course of time, the virus will go away and then things will get normal."

Did anything else get cheaper?

The cost of clothing and footwear also fell significantly. And in an indication of the severe effect of the pandemic on travel and tourism, air fares dropped in price as fewer people travelled abroad because of quarantine restrictions.

The ONS said this was unprecedented for August, which is usually the peak month of the holiday season.

"The cost of dining out fell significantly in August thanks to the Eat Out to Help Out scheme and VAT cut, leading to one of the largest falls in the annual inflation rate in recent years," said ONS deputy national statistician Jonathan Athow.

"For the first time since records began, air fares fell in August as fewer people travelled abroad on holiday. Meanwhile, the usual clothing price rises seen at this time of year, as autumn ranges hit the shops, also failed to materialise."

It was the lowest inflation rate since December 2015.

What is inflation?

Inflation is the rate at which the prices for goods and services increase.

It affects everything from mortgages to the cost of our shopping and the price of train tickets.

It's one of the key measures of financial well-being, because it affects what consumers can buy for their money. If there is inflation, money doesn't go as far.

What does this mean for the economy?

A five-year low in the rise in consumer prices reflects the extraordinary action taken to try to get Brits back into town centres. The fall to 0.2% is overwhelmingly the result of the impact of Eat Out to Help Out and the temporary VAT cut for the hospitality sector.

It is a statistic that reaffirms what we already know, but also reflects some freakishly temporary factors. The chancellor's restaurant subsidy scheme is already over, the VAT cuts expire in January.

Inflation is likely to remain lower than its 2% target, except in the case of a further sharp fall in the value of the pound - for example, after a disorderly end to the post-Brexit trade talks. Either way, the Bank of England has more space for extra support to the economy in the coming months, without risking a surge in inflation.

Are prices going to fall any lower?

Probably not. Before the latest figures were published, there had been fears that the UK inflation rate might turn negative, giving rise to what is known as deflation.

Economists fear deflation because falling prices lead to lower consumer spending, as shoppers put off big purchases in the expectation that they will get cheaper still.

Thomas Pugh, UK economist at Capital Economics, said August's figure was probably "the low point" for inflation, but pointed out that it was unlikely to hit the Bank of England's 2% target within the next few years.

"The big picture is that it will be a few years before the economy is strong enough to sustain CPI inflation at the 2% target," he said.

"The big risk to this view is a no-deal Brexit, which could cause a slump in the pound and, in turn, a temporary sharp rise in inflation to above 3.5%."

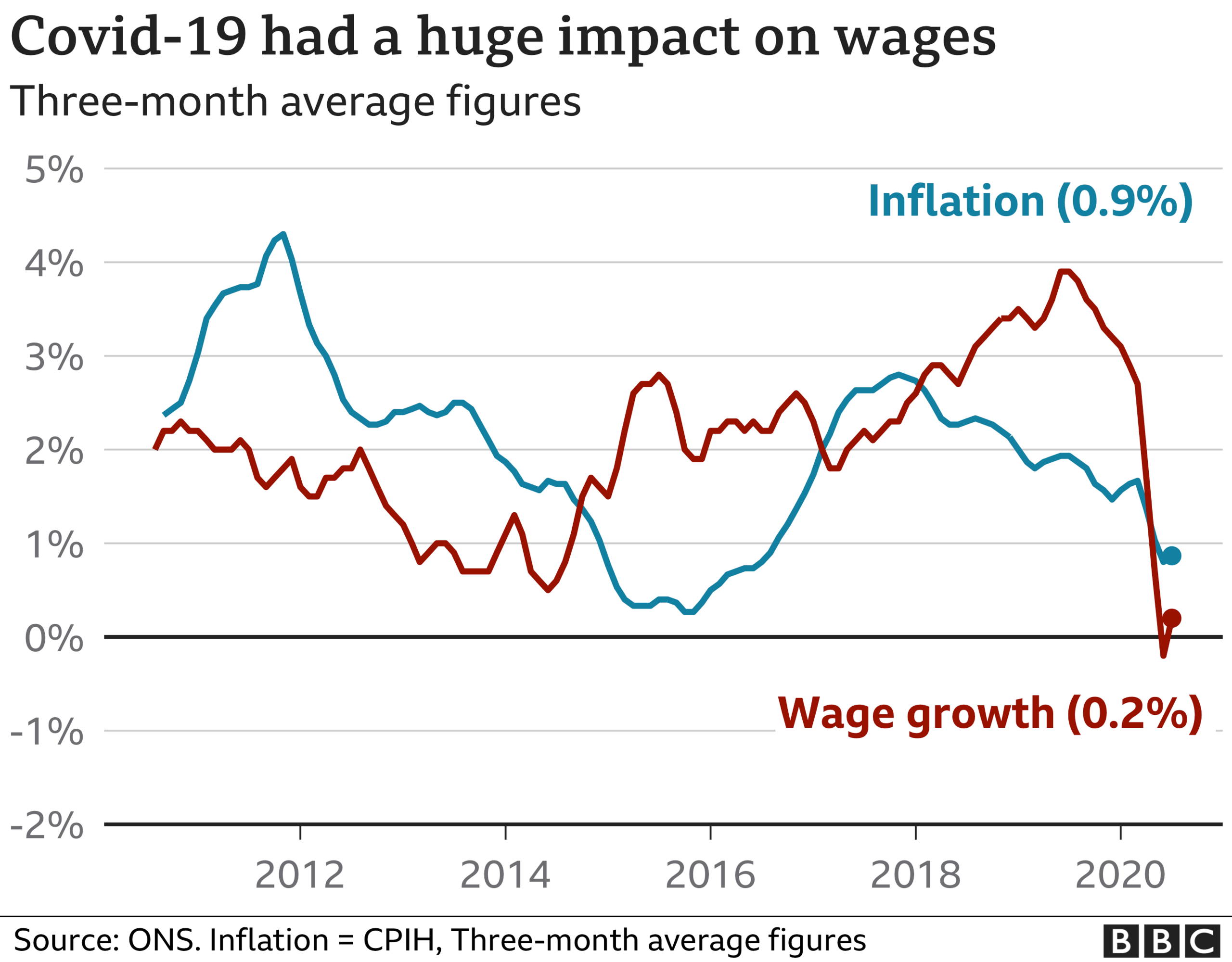

Does this put more money in my pocket?

Not necessarily. Although prices went up very little in August, a look at the figures over the past three months shows that on average, inflation has outstripped growth in pay.

Inflation is calculated by looking at a "basket" of commonly purchased goods and comparing how much they cost now with last month and with the same time last year.

During the pandemic, the ONS has been unable to identify prices for many of the 720 items it usually monitors.

In August, the ONS said prices for only eight items were still unavailable, reflecting parts of the economy still unable to operate normally including cruises, live music, theatre, swimming pools and soft play sessions.

- Published15 September 2020