Covid-19: UK could face 50,000 cases a day by October without action - Vallance

- Published

Chief Scientific Officer Sir Patrick Vallance says measures must be taken to stop the spread of Covid-19

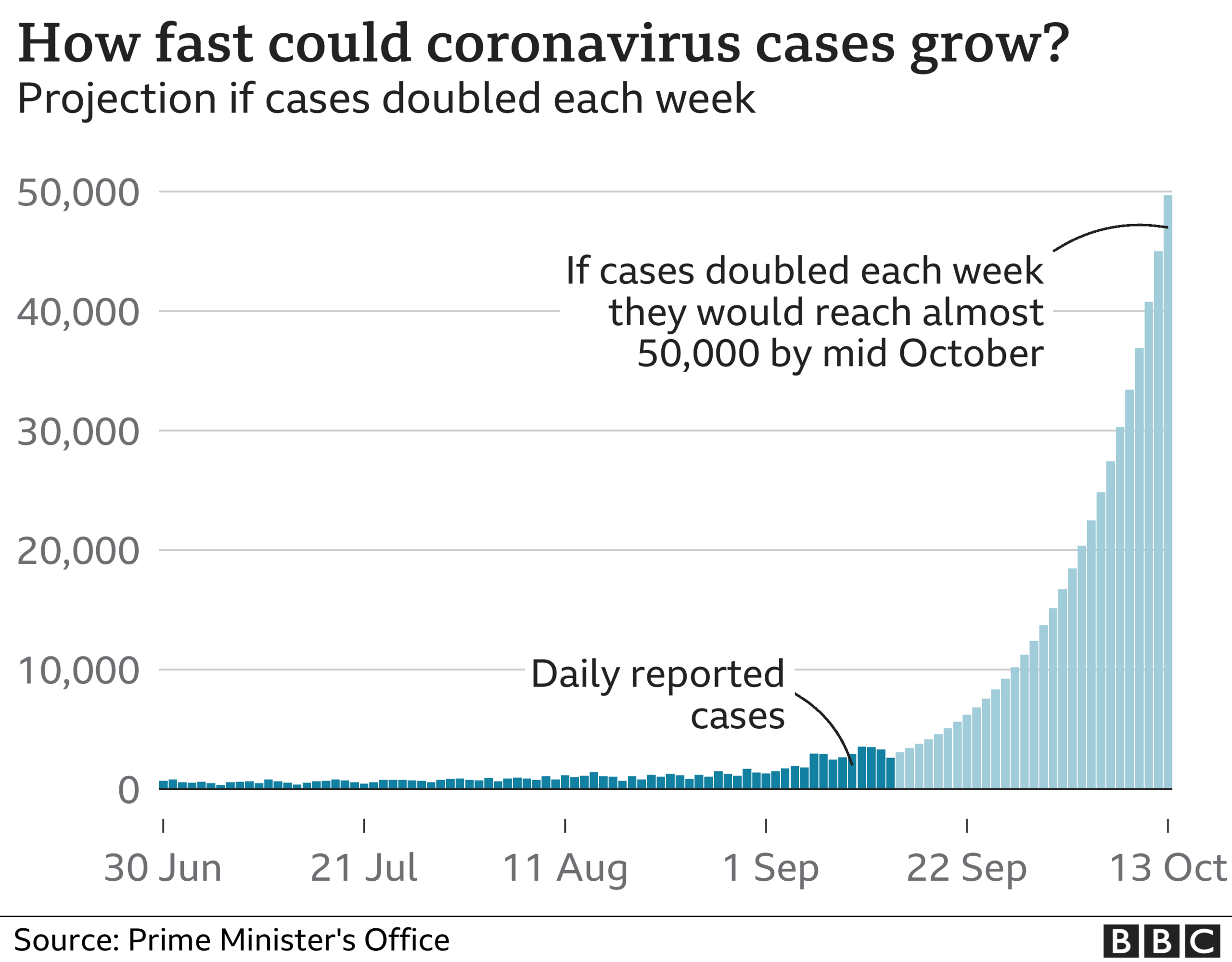

The UK could see 50,000 new coronavirus cases a day by mid-October without further action, the government's chief scientific adviser has warned.

Sir Patrick Vallance said that would be expected to lead to about "200-plus deaths per day" a month after that.

It comes as the PM prepares to chair a Cobra emergency committee meeting on Tuesday morning, then make a statement in the House of Commons.

On Monday, a further 4,368 daily cases were reported in the UK, up from 3,899.

A further 11 people have also died within 28 days of a positive test, although these figures tend to be lower over the weekend and on Mondays due to reporting delays.

Speaking at Downing Street alongside chief medical adviser, Prof Chris Whitty, Sir Patrick stressed the figures given were not a prediction, but added: "At the moment we think the epidemic is doubling roughly every seven days.

"If, and that's quite a big if, but if that continues unabated, and this grows, doubling every seven days... if that continued you would end up with something like 50,000 cases in the middle of October per day.

"Fifty-thousand cases per day would be expected to lead a month later, so the middle of November say, to 200-plus deaths per day.

"The challenge, therefore, is to make sure the doubling time does not stay at seven days.

"That requires speed, it requires action and it requires enough in order to be able to bring that down."

Prof Whitty added that if cases continued to double every seven days as Sir Patrick had set out, then the UK could "quickly move from really quite small numbers to really very large numbers because of that exponential process".

"So we have, in a bad sense, literally turned a corner, although only relatively recently," he said.

Prof Whitty and Sir Patrick also said:

The rising case numbers can not be blamed on an increase in testing as there is also an "increase in positivity of the tests done"

Around 70,000 people in the UK are estimated to currently have the disease - and about 6,000 per day are catching it (based on an ONS study)

Less than 8% of the population has been infected, although the figure could be as high as 17% in London

The rising transmission is a serious "six-month problem that we have to deal with collectively" - but science will eventually "ride to our rescue"

The virus is not milder now than in April, despite claims to the contrary

It is possible "that some vaccine could be available before the end of the year in small amounts for certain groups" but "the first half of next year" is much more likely

The government's most senior science and medical advisers are clearly concerned about the rise in cases that have been seen in recent weeks.

The warning about 50,000 cases a day by mid-October is stark. We don't know for sure how many cases there were at the peak in spring (as there was very limited testing in place) although some estimates put it at 100,000.

However, they were also at pains to point out it was not a prediction - for one thing the 'rule of six' which came in just a week ago has not had time to have an impact.

Even among the government's own advisers there is disagreement over whether what we are seeing is the start of an exponential rise or just a gradual increase in cases, which is what you would expect at this time of year as respiratory viruses tend to circulate more with the reopening of society.

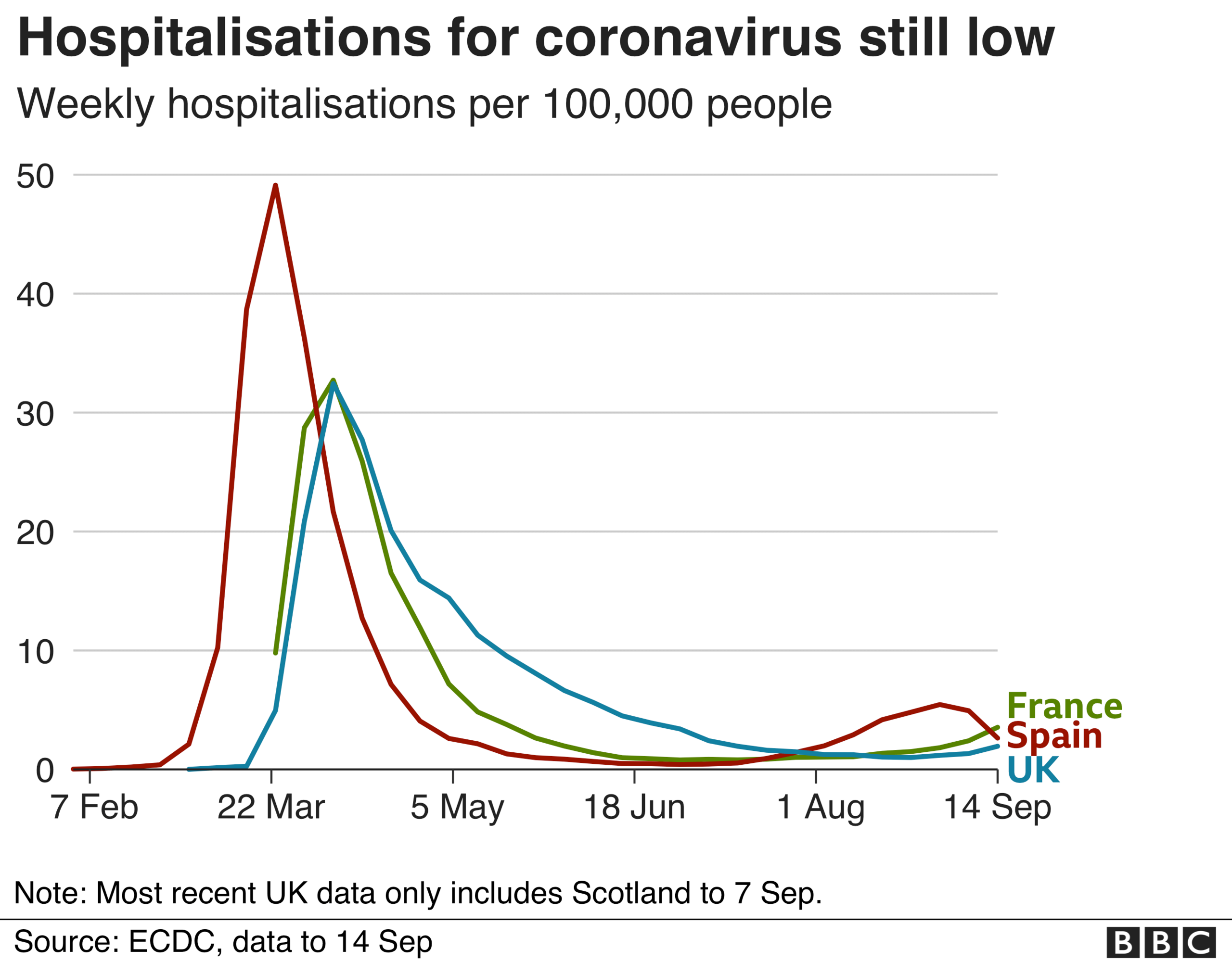

Spain and France, which both started seeing rises earlier than the UK, have not seen the sort of rapid trajectory that was presented by the advisers.

Instead, what was quite telling was the clear social messaging. Even those who are not at a high risk of complications should, they say, play their part in curbing the spread of the virus - because if it spreads then difficult decisions will be needed that have profound societal consequences.

But the big unanswered question is what ministers will do next. There is talk of further restrictions being introduced.

A couple of things are in our favour that were not in the spring. Better treatments for those who get very sick are now available, while the government is in a stronger position to protect the vulnerable groups.

Should ministers wait and see what happens? Or should they crack down early, knowing that will have a negative impact in other ways?

Prof Whitty also said that even though different parts of the UK were seeing cases rising at different rates, and even though some age groups were affected more than others, the evolving situation was "all of our problem".

He added that evidence from other countries showed infections were "not staying just in the younger age groups" but were "moving up the age bands".

He said mortality rates from Covid-19 were "significantly greater" than seasonal flu, which killed around 7,000 annually or 20,000 in a bad year.

Meanwhile, restrictions on households mixing indoors will be extended to all of Northern Ireland from 18:00 BST on Tuesday.

Areas in north-west England, West Yorkshire, the Midlands and four more counties in south Wales will also face further local restrictions from Tuesday.

And additional lockdown restrictions will "almost certainly" be put in place in Scotland in the next couple of days, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has said.

"Hopefully this will be with four-nations alignment, but if necessary it will have to happen without that," she said.

Welsh Health Minister Vaughan Gething added: "It may be the case that UK-wide measures will be taken but that will require all four governments to exercise our varying share of power and responsibility to do so."

Prime Minister Boris Johnson spoke with leaders of the devolved administrations on Monday afternoon.

Meanwhile, Health Secretary Matt Hancock announced a new exemption to local restrictions in England for formal and informal childcare arrangements, covering those looking after children under the age of 14 or vulnerable adults.

"It does not allow for play-dates or parties, but it does mean that a consistent childcare relationship that is vital for somebody to get to work is allowed," he told the Commons.

It is not a question of "if".

Downing Street will have to introduce extra restrictions to try to slow down the dramatic resurgence of coronavirus.

You would only have to have dipped into a minute or two of the sober briefing from the government's most senior doctor and scientist on Monday morning to see why.

What is not yet settled however, is exactly what, exactly when, and indeed, exactly where these restrictions will be.

Here's what it is important to know:

The government is not considering a new lockdown across the country right now.

The prime minister is not about to tell everyone to stay at home as he did from the Downing Street desk in March.

Ministers have no intention at all to close schools again.

Nor, right now, are they planning to tell every business, other than the non-essential, to close again.

What is likely is some kind of extra limits on our huge hospitality sector.

On Sunday, the prime minister held a meeting in Downing Street with Prof Whitty, Chancellor Rishi Sunak and Health Secretary Matt Hancock to discuss possible further measures for England.

Asked about reports of disagreements among cabinet ministers about whether or not to impose a second lockdown, Transport Secretary Grant Shapps told BBC Breakfast: "A conversation, a debate, is quite proper and that is exactly what you'd expect.

"Everyone recognises there is a tension between... the virus and the measures we need to take, and the economy and ensuring people's livelihoods are protected."

Prof Peter Horby, a member of the government's Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage), said there was a risk the UK could face a repeat of the "catastrophic events" around the world early this year, with intensive care units "rammed full of very sick patients".

"I really don't buy that argument that we should slow down... the mistakes that were made in March were nearly all being too cautious and too slow," he told BBC Radio 4's World at One.

However, Prof Karol Sikora, from the University of Buckinghamshire and former director of the World Health Organization's cancer programme, said blanket restrictions were "not the way forward".

"The most important thing is to target the groups that we need to protect and to let everybody else get on with their business - schools, shops and so on," he told the programme.

Labour, meanwhile, has also urged the government to avoid a second national lockdown.

"This rapid spike in infections was not inevitable, but a consequence of the government's incompetence and failure to put in place an adequate testing system," shadow health secretary Jonathan Ashworth said.

"The government must do what it takes to prevent another lockdown, which would cause unimaginable damage to our economy and people's wellbeing."