Supreme Court President Lord Reed wants more diversity in Supreme Court

- Published

Lord Reed has spoken to the BBC about the lack of people from black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds among the Supreme Court's 12 justices

The new Supreme Court president says he hopes a justice from an ethnic minority background will be appointed before his retirement in six years' time.

Lord Reed said the lack of diversity among the 12 Supreme Court justices was a situation "which cannot be allowed to become shameful if it persists".

Only 4% of senior judges appointed to the High Court or above are from ethnic minority backgrounds.

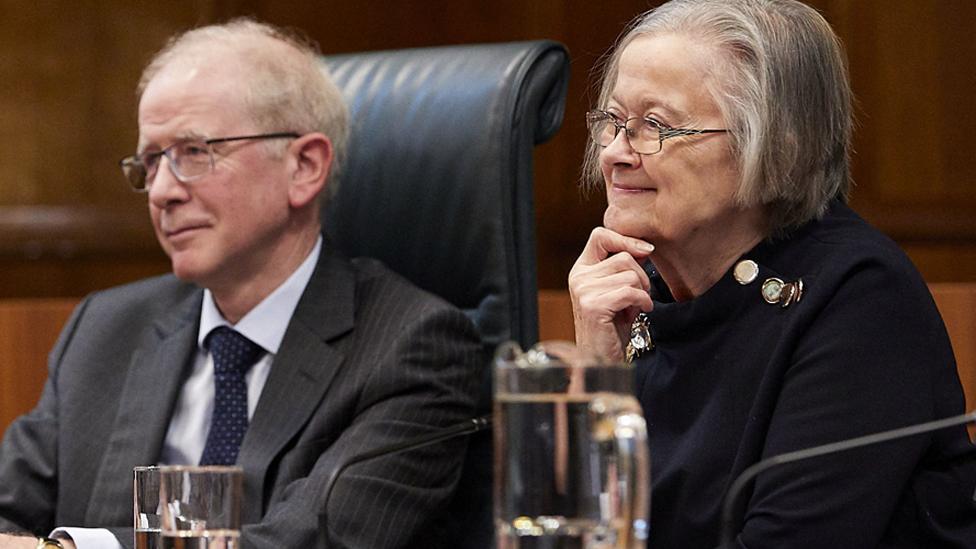

Lord Reed has taken over as president of the Supreme Court from Lady Hale.

In his first media interview since taking on the role, and when asked when there might be a justice from a black, Asian or minority ethnic background appointed to the court, Lord Reed told the BBC: "I hope that will be before I retire which is in six years' time."

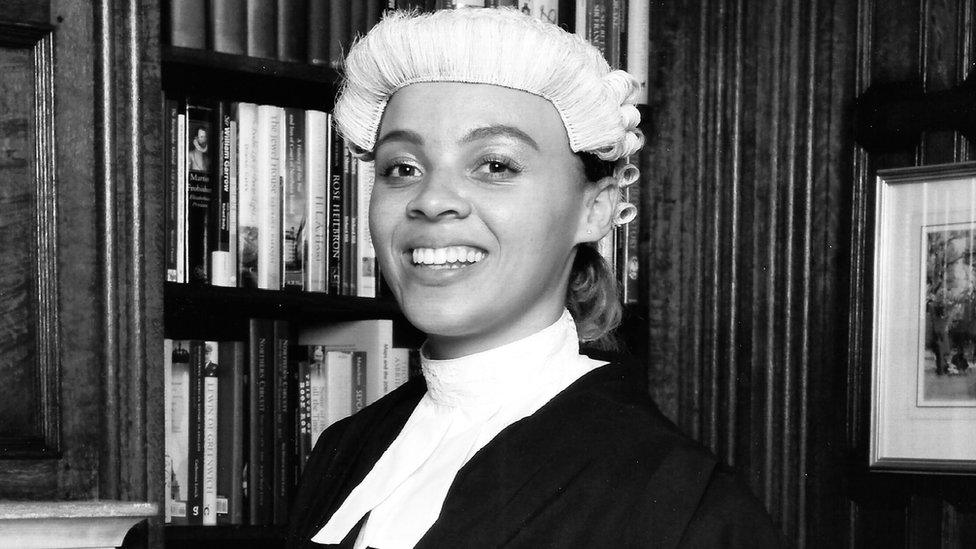

Last month black barrister Alexandra Wilson was mistaken for a defendant three times in the same morning at a magistrates' court.

"I thought that was appalling," Lord Reed said.

"Alexandra Wilson is a very gifted young lawyer, an Oxford graduate who has won umpteen scholarships, and for her to be treated like that was extremely disappointing to say the least," he said.

Ms Wilson received an apology from Her Majesty's Courts and Tribunals Service for "the totally unacceptable behaviour".

Asked about a judge of South Asian heritage who was mistaken on numerous occasions for the court clerk, he said: "That is down to ignorance and unconscious bias which has to be addressed by the courts service."

Alexandra Wilson, who specialises in family and criminal law, said she did not expect to "constantly justify my existence at work"

Diversity has remained a stubbornly difficult issue for the judiciary which has often been described as "stale, male and pale".

Currently just 4% of senior judges appointed to the High Court or above are from a black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds.

The figure rises to 8% of lower court judges and 12% of tribunal judges, a 2% increase compared with 2014 in both cases.

The representation of women is better, but still unequal.

Currently 32% of court judges and 47% of tribunal judges are women.

The proportion has increased in recent years, but remains lower in senior court appointments with women making up just 26% of High Court and more senior judges.

Until Lady Hale's departure there were three female Supreme Court justices.

Role of the UK Supreme Court

Often called the highest court in the land, the Supreme Court is a big beast.

It is the final court of appeal for all UK civil cases and criminal cases from England, Wales and Northern Ireland as well as hearing appeals on points of law of great public and constitutional importance.

Unlike its more powerful US counterpart, it cannot strike down legislation, but it can judicially review the actions of ministers and other public bodies and decide if they are lawful.

That gives it huge power, seen to the full last year when the court unanimously declared "unlawful" the advice Prime Minister Boris Johnson gave the Queen to suspend Parliament in the lead up to the Brexit deadline.

Lord Reed succeeded Lady Hale as President of the Supreme Court

It showed that independent judges can halt the might of government in its tracks if ministers have acted unlawfully and that no-one is above the law. That led some to accuse the court of judicial activism.

"What we are doing isn't activism. It's giving effect to the law," Lord Reed said.

"The fact that some of the topics can be politically sensitive is something which we cannot allow to deter us from applying the law which Parliament has enacted. That's what we're here for."

The government has set up a panel to examine judicial review.

It will consider whether certain executive decisions should be decided on by judges, and which grounds and remedies should be available in bringing claims against the government.

Government 'activist lawyers' video 'unfortunate'

Lord Reed was not impressed with a Home Office video, tweeted in August, which described "activist" lawyers who represent migrants arguing they have a right to remain in the UK.

The animated video said current regulations were open to abuse allowing "activist lawyers" to delay and disrupt returns.

"I think that was unfortunate and I understand that the government has acknowledged that.

"There is no question of people being activist simply because they are doing their job," he said - underscoring that the lawyer's job is to see clients get the treatment they are entitled to by law.

The government took down the video, but some saw its posting as as a deliberate attempt to pick a fight with lawyers, in order to deflect attention from the fact that migrants claiming asylum are sometimes unlawfully removed from the UK in breach of international human rights laws.

Lord Reed acknowledged there was a risk in applying the label "activist" to lawyers and then withdrawing it because it can lodge in the public's mind.

"It's important that people are careful in the language that they use," he said.

'Vision' for the court

Lord Reed wants to maintain the standing of the Supreme Court as "one of the very top courts in the world whose judgements are cited and followed by other courts around the world".

However, at a time when the government has placed the constitutional role of judges under intense scrutiny, he is keen to strengthen the relationship between the court and Parliament.

"Some of the reaction to the judgements that we gave relating to actions government was taking in the course of the Brexit negotiations revealed a lack of understanding of what our role was or how we operate - and perhaps a degree of suspicion of what our motives might be," he acknowledged.

So, he is exploring with the Speaker's office how to enable members of Parliament to question and discuss with the justices how they decide cases.

Understandably, Lord Reed would not be drawn on the Internal Market Bill which enables the government to break its international treaty obligations under the EU Withdrawal Agreement.

It is, after all, still before Parliament.

But in the next six years the Supreme Court is likely to remain locked into what is perhaps the constitutional clash of our times, between a powerful government that wants to get its way on policy decisions, and independent judges whose role is to scrutinise the lawfulness of those decisions.

Could be a bumpy ride.

- Published4 October 2020

- Published24 September 2020

- Published13 January 2020

- Published13 January 2020