Belly Mujinga's death: Searching for the truth

- Published

The death of transport worker Belly Mujinga following reports she had been spat at by a customer, sparked calls for justice from millions of people. Now a BBC investigation raises questions about the inquiries carried out by her employer and the police.

It was a chilly morning when Belly Mujinga caught the bus to Victoria station in central London. Shivering, the 47-year-old ticket office worker pulled on her favourite gloves and sat down. It was 04:45 and outside the sky was a murky grey; the sun had yet to rise.

It was Saturday 21 March, and fears about Covid-19 were intensifying. The government had advised against unnecessary travel and non-essential contact with others. Schools had closed to all but vulnerable children and those of key workers.

Days earlier, Prime Minister Boris Johnson had announced that by the weekend those with the "most serious health conditions" must be "largely shielded from social contact".

Belly, who had severe health problems that had affected her lungs and throat, was anxious about coronavirus. She'd previously had treatment on her throat after having difficulty breathing.

The 47-year-old had stressed the importance of social distancing in a recent video she had made on the station concourse for her family in Congo. "There's no people. People are afraid. People are home. See the ticket office is empty, everyone is afraid because of Covid. Stay at home," she says, her face peeping out from under her black scarf.

"But we are here, we have to work. I love you and be safe."

The incident

On the morning of 21 March, Belly and her colleague Motolani Sunmola, were working on the concourse. At around 11:20, they were approached by a male customer. What happened next is disputed. Four people were present at the time: Belly, Motolani, a male colleague, and the customer.

Motolani - who is speaking publicly for the first time - says the man, who was casually dressed in blue jeans and a tan jacket, sharply asked them twice what they were doing. She describes him as being agitated and aggressive. "He was screaming and shouting at us," the 52-year-old says.

Motolani Sunmola

"We told the gentleman, 'Please we're just here to help you, that's all why we're here'." She said the man then turned and took a few steps towards the ticket office. "Out of nowhere he came back again and said: 'You know I have the virus'," Motolani alleges. As he came closer, Motolani said she and Belly retreated and asked him to "behave" himself.

Motolani says he was "coughing and spitting like an old man who has no teeth," and they ran away. She says Belly rushed into the reception to wash the spray of saliva from her face.

When Belly later returned home, her husband Lusamba says she was unusually quiet. "She was sad. She told me, 'Darling, someone spat on me'. It really shook her."

Belly, Lusamba and their daughter Ingrid

'Scared'

In the days that followed, Motolani and Belly began to feel unwell.

Belly's last day at work was 25 March. One of her consultants called a manager at her request to say she needed to self-isolate immediately.

Her symptoms started to escalate and on 2 April, when she was struggling to breathe, Lusamba called an ambulance. "On her way out, she waved our daughter and me goodbye," he says.

Belly was diagnosed with Covid-19 at the Barnet Hospital in north London.

Lusamba says she was scared and "knew that was the end".

During a video-call on Saturday 4 April, she spoke to her family but refused to show her face. She didn't want her daughter Ingrid, who was 11 at the time, to see her in such a weak state.

Shortly afterwards, she called her cousin Agnes Ntumba and asked her to look after Ingrid for her. Later that evening, Lusamba tried calling his wife. But she didn't pick up.

Belly Mujinga died from coronavirus on Sunday 5 April.

Lusamba struggled to understand when the doctor told him over the phone. English is not his first language, as he mainly speaks French and the Congolese-dialect Lingala, so Agnes had to break the news to him hours later.

A funeral was held three weeks later, but only 10 people were allowed to attend.

"It feels like she's just gone somewhere and will come back," Lusamba says. "Since I didn't see her body, it's as if my brain can't process it. It will haunt me for the rest of my days."

Police investigation

It would be seven weeks before a police investigation was launched.

It came after the Transport Salaried Staffs' Association (TSSA) issued a press release on 12 May stating that Belly and a colleague had been assaulted.

Reports that a ticket officer had died of coronavirus after being spat at while on duty made newspaper headlines.

British Transport Police (BTP) opened an investigation, and on 13 May, Boris Johnson mentioned Belly's death in Parliament. "The fact that she was abused for doing her job [was] utterly appalling," he said.

BTP traced and interviewed a 57-year-old man through ticket sales records at Victoria station. He denied spitting and saying he had the virus. He said he had coughed, but not on purpose.

After an investigation lasting 19 days, the police concluded there was insufficient evidence to charge anyone with a crime.

Lusamba says this came as a shock. "It was a hard pill to swallow, especially after such a short investigation."

The police decision coincided with the death in Minneapolis of George Floyd, while in police custody. Global outrage followed and anti-racism protests that had swept across cities in the US were heading to the UK. Belly's death was caught up in the aftermath.

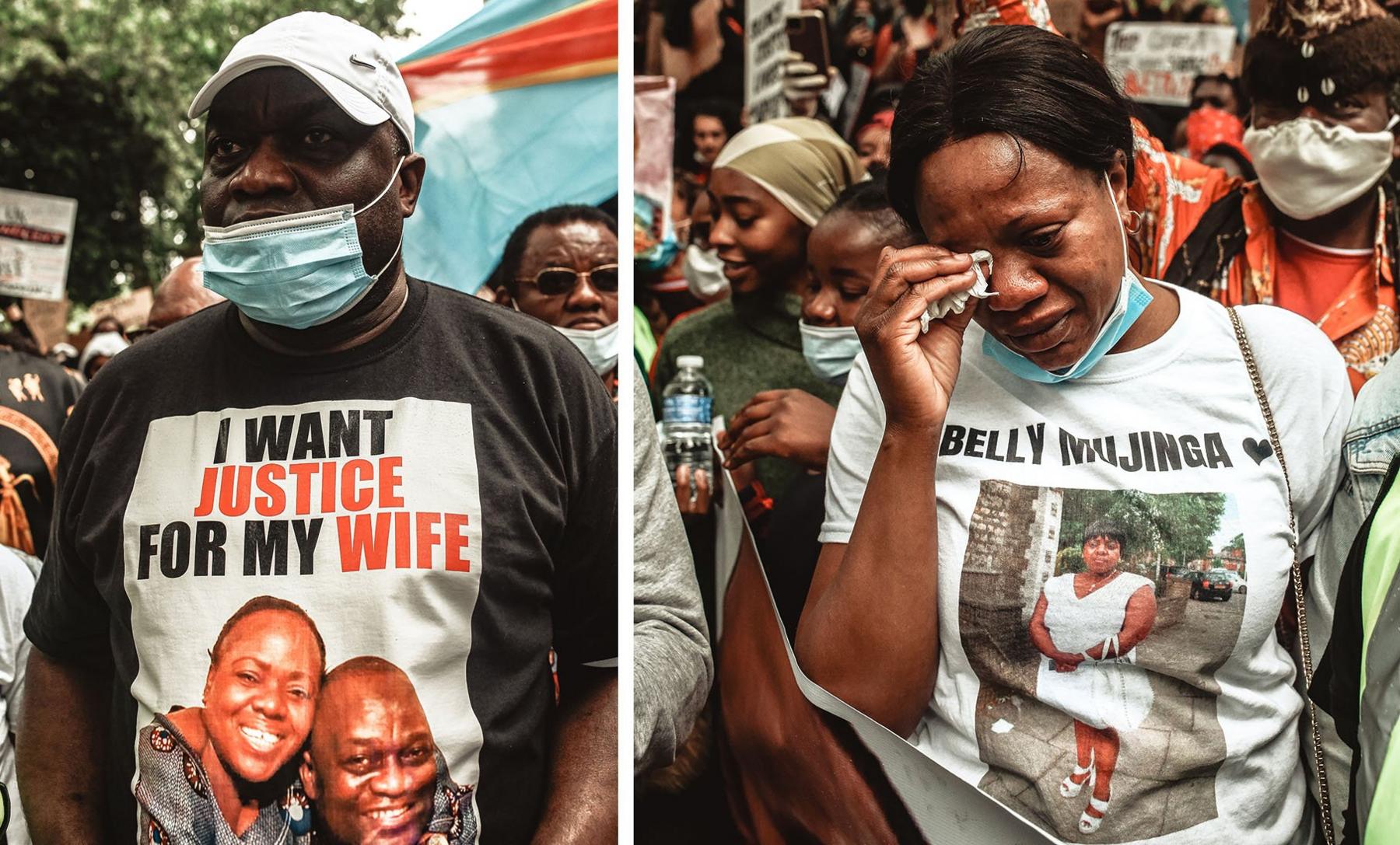

Agnes at the 'Justice for Belly' rally

"Black lives matter. Belly's life mattered," protestors shouted at a march in London on 3 June.

Naomi Omokhua, 21, helped to organise a "Justice for Belly" rally. "We see people like Belly every day when we're going through Victoria station," she says. "She's a black woman, a normal black woman just doing her job."

Lusamba and Agnes

Lusamba attended with Ingrid and Agnes. "We laughed and cried," he says. "We felt pain and joy. I'll never forget that day."

In the wake of the protests, on 5 June, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) was asked by the British Transport Police to review the case.

And as that inquiry opened, so did mine for BBC Panorama.

Looking for answers

What happened at Victoria station has been the subject of a police investigation and an internal inquiry carried out by GTR. The facts remain bitterly contested, so I've been back over some of the evidence and taken expert opinion from doctors, scientists and lawyers.

First, I wanted to know why it took so long for the police to investigate. It's possible that if they had been alerted sooner, they may have been able to secure more evidence.

Motolani has left Govia Thameslink Railway (GTR) and begun a claim for constructive dismissal. In her police statement of 13 May, she says she reported the incident to her managers immediately, asking for the police to be called.

LOCKDOWN LOOK-UP: The rules in your area

SOCIAL DISTANCING: How have rules on meeting friends changed?

SUPPORT BUBBLES: What are they and who can be in yours?

FACE MASKS: When do I need to wear one?

Lusamba says Belly told him the man had said he had coronavirus and was going to infect them and that she had reported the incident to a supervisor. Motolani told the BBC she had described what happened as an "assault". She says she did not tell GTR on the day that the man said "I have the virus" but says Belly did.

"I felt the assault was even more serious," Motolani explains. "Belly felt more scared [of the word Covid] because she had respiratory problems."

A GTR spokesperson told the BBC that while a "coughing incident" had been logged on 21 March, a spitting incident had not and that's why the police hadn't been called.

On 8 April, Belly's union wrote to GTR saying there was evidence that a passenger had deliberately coughed in Belly's face. GTR says it started its own investigation. The company did not call the police. An allegation of deliberate coughing can be enough for the police to consider opening an assault investigation.

When BTP was eventually called, the man said he'd had an antibody test - which checks whether someone has previously been exposed to the virus - and that he had tested negative. Police said the man had been tested on 25 March "as part of his occupation" and the result shared with them. Detectives concluded, therefore, that the incident had not led to Belly contracting Covid-19.

I spoke to a number of scientists about antibody tests. They said not all commercially available antibody tests back in March were considered reliable. The NHS didn't start offering antibody tests to all staff until May.

"The quality of the tests available in March were really no better than tossing a coin," says Alex Richter, a Professor of Clinical Immunology at the University of Birmingham, who had studied some of the early tests back then.

A negative result did not necessarily mean there had been no infection.

Jon Deeks, Professor of Biostatistics at the University of Birmingham, believes the police made a mistake in their interpretation of this part of the evidence.

In a statement, BTP told the BBC: "While the man was able to share a negative antibody test with officers, substantiated by his GP, it is important to be clear that this was not the basis of our conclusion. The test did not change the fact there was insufficient evidence to substantiate any criminal offences taking place."

One of the problems with the case is that CCTV evidence was not sufficiently clear to show whether or not a crime had taken place. There are hundreds of security cameras at Victoria station but Network Rail, which operates them, told the BBC that only one captured footage of the incident.

The footage has not been released, but I've spoken to a number of people who have seen it. I've also listened to a covert audio recording of a meeting in which police officers showed it to Lusamba and two of his friends.

They say it shows a man approaching close to Belly, and her retreating, before running away.

"We're in no doubt that something has happened there," the police officer tells Lusamba. "If nothing had happened, they would have stayed there," the officer continues. "When he comes back it's clear that's when something happens."

CCTV footage at the station is routinely only stored for around 28 days, and the footage from 21 March had been wiped by the time the police started their investigation.

But officers were told that six minutes had been saved at the request of GTR. The BBC has learnt that GTR asked for footage on 9 April as part of its own investigation and received a copy the following day.

The police say that even after they had had the footage enhanced, it was still not clear enough to show whether a crime had been committed.

Internal report

Belly Mujinga suffered from a severe form of sarcoidosis, a rare inflammatory condition that causes small patches of red and swollen tissues to develop in the body's organs.

"We were dealing with people from all around the world," Motolani said. "She was scared of catching the flu, then imagine this happening."

The company told the BBC that on 13 March, local managers had issued a staff questionnaire to identify any health conditions that might restrict their ability to work in public facing areas. But said Belly had only recorded "blood pressure" on her form. According to GTR she had asked Occupational Health to keep her condition confidential.

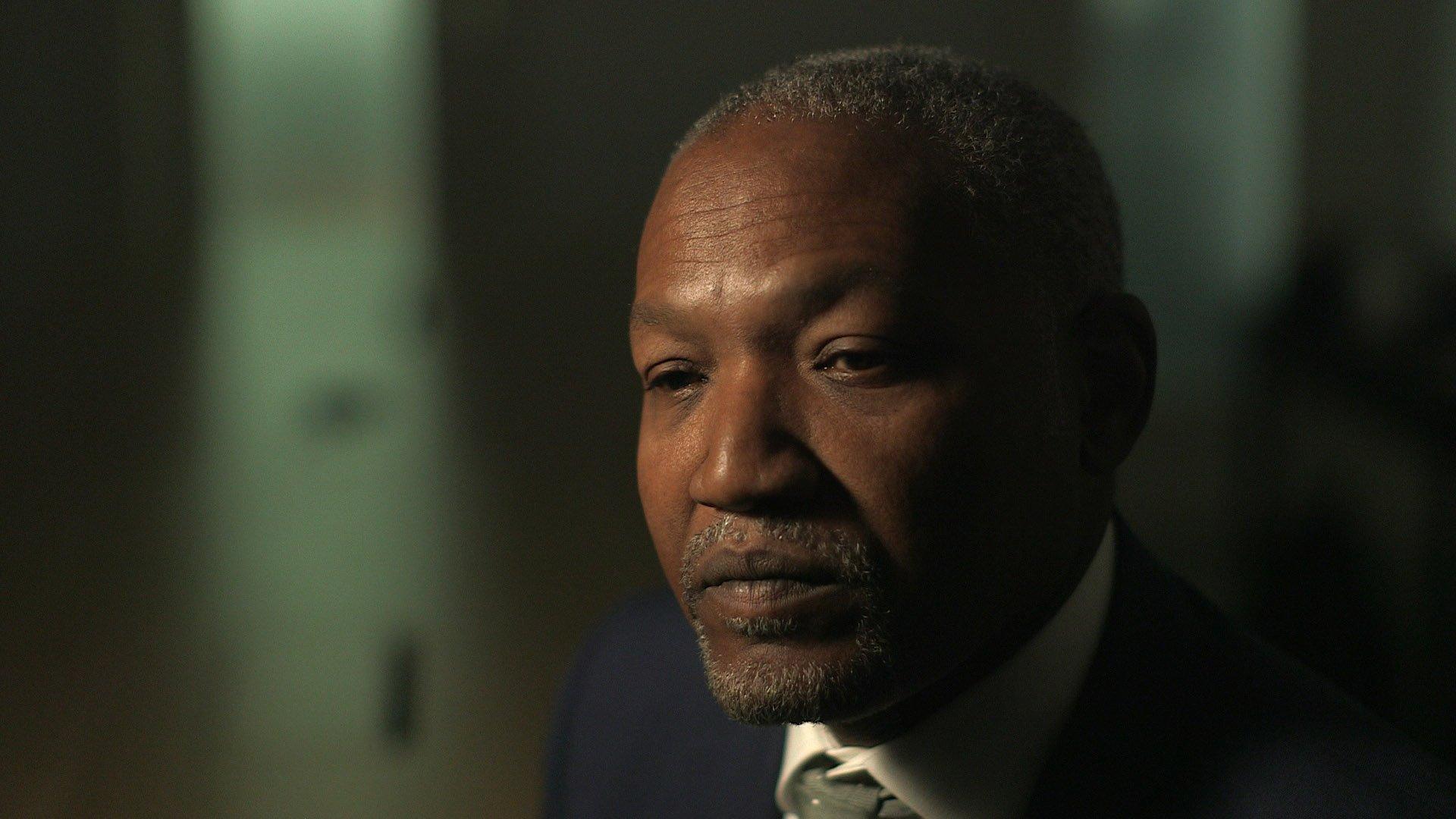

Martin Forde QC

In its internal investigation report after her death, the company said that her managers were aware she had some health conditions that meant Belly had regular medical check-ups but "did not know the exact details and nature of these".

But in a different version of the report, which had been shared with Belly's union and seen by the BBC, it suggested they may have known more.

"Managers at the station were aware that Mrs Mujinga had undergone surgery on her throat some years previously and that she had regular check-ups in relation to this," it said.

"I think it arouses a degree of disquiet in me because here, there's such a contrast between those versions," says Martin Forde QC.

GTR told the BBC that Belly's sarcoidosis would have been on the records of its in-house medical team, but said it was not at that time on the government's list of high-risk conditions.

Belly was taking immunosuppressants for her sarcoidosis. On the day of the incident itself, the government was issuing guidance for people taking immunosuppressants, saying that they should shield.

Barrister Elaine Banton said she would have expected more collaboration between the occupational health team and managers to identify vulnerable staff.

"It would help them to determine which employees should not be in front-facing, key worker roles, but be placed out of harm's way."

A GTR spokesperson says had sarcoidosis been on the government's shielding list at the time of the incident, it would have told Belly to shield as it did with nearly 400 colleagues.

But was there a need for Belly to be on the concourse that day? Passenger numbers were down.

"She left home thinking she was going to be working in the ticket office," Lusamba said. "When she arrived, her supervisor told her that she must work outside."

Rotas from the 21 March, seen by the BBC, confirm that Belly was due to work in the ticket office. Motolani says she felt safer there.

GTR says all ticket office staff at Victoria undertake concourse duties as part of their normal ticket selling and customer assistance role.

Grievance

Belly loved her job, but I've discovered she wasn't always happy at work.

Eight weeks before she died, she'd raised a grievance against GTR, claiming discrimination and victimisation.

In 2019, Belly had been suspended for six weeks after leaving her cash bag on a supervisor's desk rather than handing it into the cashier.

"She was devastated," recalls Lusamba. "That really broke her." He says GTR conducted an investigation to see whether money was missing but they didn't find anything.

GTR said Belly had a responsible cash handling role, that she was suspended on full pay and later returned to work.

However, Belly claimed a white colleague who had made a similar mistake had not faced the same sanction.

In her grievance letter she wrote, "The whole process has left me feeling stressed, ill, victimised and terrified that I might lose my job."

'May she rest'

Lusamba says Belly was the "centre of his universe", and he believed that fate had brought them together. It later turned out that he had been living very near to one of Belly's close friends in Kinshasa, the capital of Congo, where he grew up.

He and Belly met at a church they both attended after she moved to London in 2001. "It was love at first sight," he says.

Their daughter Ingrid turned 12 and returned to school in September. Only this time it was her dad buying her ice-cream, and gently laying out her school uniform on her bed.

Lusamba says all he wants to do is tell her what really happened to her mum.

We may never know what really happened on the concourse of Victoria Station that day. Or whether Belly caught coronavirus then.

Following its review, the CPS agreed with the police that in: "The absence of any persuasive medical or forensic evidence, together with inconclusive CCTV footage and inconsistent witness accounts, no criminal charges could be considered."

But for Lusamba, many questions remain unanswered.

Barristers spoken to by the BBC believe an inquest into Belly's death could help her family in their search for truth. "I feel there are sufficient doubts and conflicts around the facts of this case to justify an investigation," says Martin Forde, QC.

Lusamba says he will keep on fighting. "May she rest wherever she is, but it's really hard."