Slow map: Mapping Britain's intercity footpaths

- Published

Would you know the best way to walk from Leeds to Manchester? From Tring to Milton Keynes, or Carlisle to Inverness? If not, then you're not alone.

We live in a time when our phones will show us the quickest route to almost anywhere - if we are driving, that is. Walking? Well, that's a different matter.

Geographer Daniel Raven-Ellison is offering a solution; a new map created by volunteers during lockdown to show the best walking routes between all of Britain's main towns.

All that is needed now is 10,000 keen walkers to test out the routes on his "slow map".

Part of the government's official transport advice during the pandemic has been "walk, if you can". It is good for keeping down both infection and congestion. It is also good for our health.

However, once you venture away from your local neighbourhood, it is not always obvious how to find the best walking route to a nearby village or - if you are feeling adventurous - a neighbouring town or city. That's what is hoped will be solved with the slow map.

'Like a plate of spaghetti'

Mr Raven-Ellison recruited 700 volunteers during the national lockdown earlier this year to plot the best routes between Britain's towns and cities, identifying 7,000 "slow routes" for anyone who wants to avoid cars or public transport on a longer journey.

Many of the slow ways follow well-known paths, but it is often far from straightforward to work out which to use or how to best get to them.

"If you look at the map of Britain it is covered in footpaths," he said. "But it's a bit like a plate of spaghetti. It's far from clear what are the best routes if you want to walk from town to town."

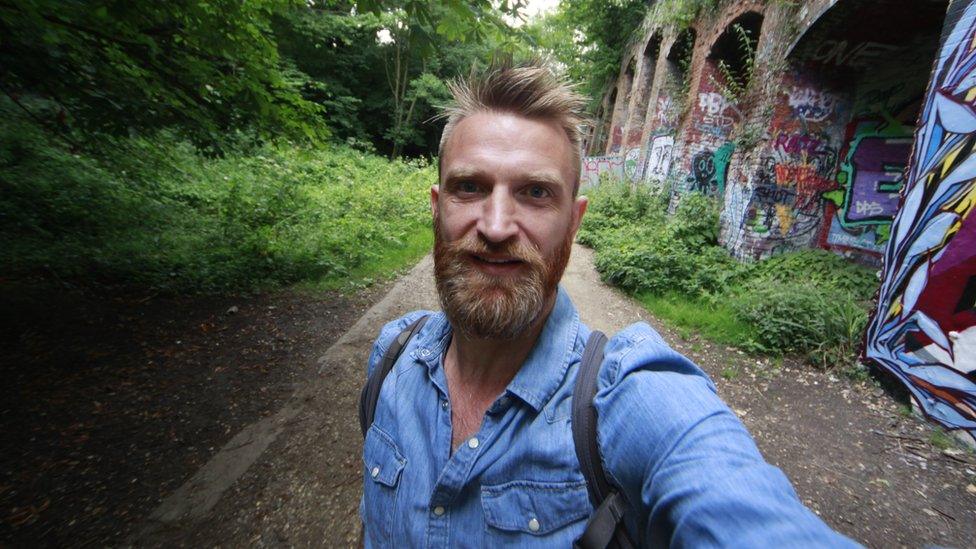

Daniel Raven-Ellison has the backing of the Ordnance Survey

He now needs more volunteers to test out the routes to ensure they are safe, walkable and pleasant. What looks a perfect route on a map can, in reality, be a muddy and almost impassable thicket of vegetation or an unpleasant scramble.

The project has the backing of the Ordnance Survey, which is planning to add the slow routes to its online database.

During lockdown, searches for urban green spaces on the OS database increased by 949%.

People were exploring their neighbourhoods on foot in a way that was, to many, entirely new. The slow map grew out of people's desires to roam further from their doorsteps.

'A national resource'

One problem the map is trying to address is that while driving and increasingly cycle routes pop up on phone sat-navs, the walking routes are far from ideal, often taking people along roads without pavements or on long unnecessary detours.

There are, of course, walking apps that can show more pedestrian-friendly routes but they are, for the most part, designed to identify the best scenic route rather than the best practical walk.

But this is about more than just coming up with some suggested pathways - it is an attempt to create a pedestrian highway system, a slow alternative to our main roads and motorways.

No one in the project is expecting large numbers of people to give up on cars and walk from city to city on a daily basis. But they hope that it can highlight thousands of shorter routes, making it easier to see how villages and settlements connect with one another.

It is not just a tool to encourage us to walk more, it is a campaigning tool. Once a route is identified, there is something to defend and to improve. It is then more than just a new resource, it is a way of trying to change a debate.

Walking is, at one level, too local and everyday an activity to generate much national attention. When walking does enter the political sphere, it is more often than not hiking or rambling that people are discussing. Walking has a long political history linked to the right to roam and access to the countryside, but this is ultimately a battle over a leisure activity, a weekend hobby that involves sturdy boots and thick socks.

The slow map seeks to elevate the position of walking in our national conversation, to be seen not just as a worthy, healthy hobby but part of our national transport infrastructure.

The numbers walking from, for example, Tring to Milton Keynes may never be great. But if even the simplest journeys between neighbourhoods involve dodging traffic on pavement-free roads, then many of us may find the only viable walk is to our cars and then to designated countryside routes back to our vehicles.

The new map is an attempt to identify a national resource and focus attention on its care and improvement.

Coronavirus is changing life in many unexpected ways and those who think more walking should be part of our lives now have a new tool. Maps do not just describe the world, they can often help change it.

To find out more about the slow map, click here, external.

- Published28 June 2020

- Published6 June 2020

- Published25 May 2020