Bletchley Park’s contribution to WW2 'over-rated'

- Published

Code-breakers at Bletchley Park in 1943

Code-breaking hub Bletchley Park's contribution to World War Two is often over-rated by the public, an official history of UK spy agency GCHQ says.

The new book - Behind the Enigma - is released on Tuesday and is based on access to top secret GCHQ files.

"Bletchley is not the war winner that a lot of Brits think it is," the author, Professor John Ferris of the University of Calgary, told the BBC.

But he said Bletchley still played an important role.

And GCHQ had a significant influence in other conflicts, according to the signals intelligence historian.

GCHQ, known as Britain's listening post, was set up on 1 November 1919 as a peacetime "cryptanalytic" unit.

During World War Two, staff were moved to Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, to decrypt Nazi Germany's messages including, most famously of all, the Enigma communications.

This provided an inside view of Nazi orders and movements.

The work was kept secret for decades but an official history of British intelligence in the war would later say it had shortened the conflict by two to four years and without it the outcome would have been uncertain.

Bletchley Park remains the most iconic success in British code-breaking and intelligence gathering. But some of the mythology surrounding it has masked the reality, the new book argues.

Nazi Germany actually had the advantage when it came to intelligence and code-breaking for the early part of the war because Britain's own communication security was so poor.

Eventually, Britain overtook the Germans and Bletchley carried out "amazing" work which did hasten victory, but not necessarily by the amount some previous estimates have claimed.

"Intelligence never wins a war on its own," says Prof Ferris.

He was given extensive access to the secret files of the intelligence agency, although some limits were placed on what he could see and write about, including more recent interceptions of other countries' diplomatic messages and some of the technical secrets of code-breaking.

'Cult of Bletchley'

The book provides a detailed sweep of the agency's contribution from its founding after World War One through to the cyber age of today, including the impact of revelations from US whistleblower Edward Snowden.

Prof Ferris writes that a "cult of Bletchley" has protected GCHQ and boosted its reputation, and argues that the fact he is able to raise questions about it show GCHQ was sincere in giving him freedom to come to his own conclusions.

"GCHQ is probably Britain's most important strategic asset at the moment and will probably remain that way for generations," he says.

"I think that Britain gains from keeping it strong and world class, but at the same time, you need to put in proportion what it is you can and cannot get from intelligence."

Bletchley was still a high-point, he said, because of the ability to get inside the enemy's strategic communications.

This was not possible against the Soviet Union in the Cold War, although GCHQ was still able to provide the majority of intelligence about its adversary's military thanks to innovative work in studying the patterns of communications.

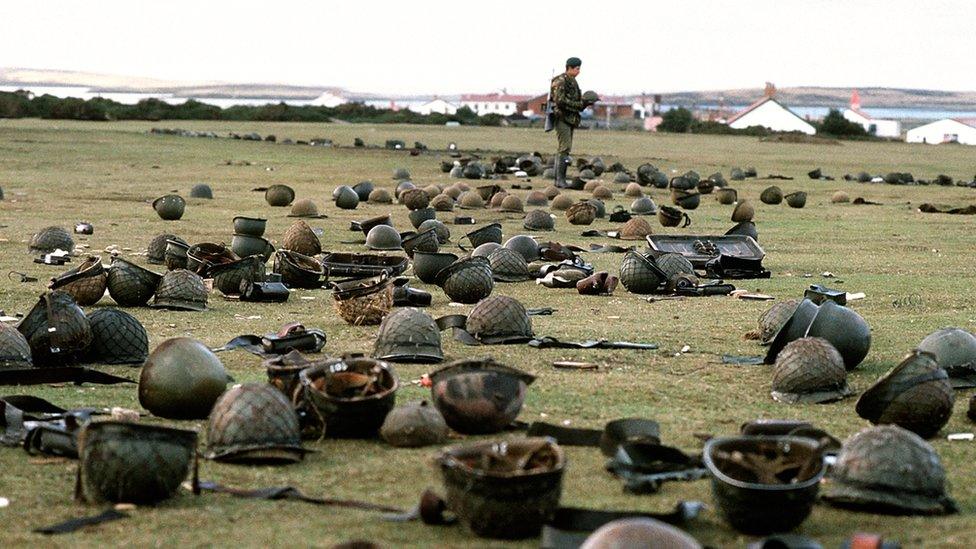

Steel helmets abandoned by Argentine armed forces who surrendered in 1982 at Goose Green to British Falklands Task Force troops

Prof Ferris also argues the agency's contribution was particularly important in the 1982 Falklands Conflict.

"I don't think Britain could have won the Falklands conflict without GCHQ," Prof Ferris told the BBC.

He said because GCHQ was able to intercept and break Argentine messages, British commanders were able to know within hours what orders were being given to their opponents, which offered a major advantage in the battle at sea and in retaking the islands.

"They understand what the Argentines planned to do. They understand how exactly the Argentines were deploying their forces."

The book provides new details on the controversial sinking of the Argentine warship Belgrano and over whether enough was done to warn of the invasion.

"It was a failure of policy, as far as I'm concerned, rather than a failure of intelligence," Prof Ferris told the BBC.

The book also details the close alliance with the US which persists to this day and how the make-up of staff who work at the agency, now based in Cheltenham, has changed over time.

In a foreword, the current director of the intelligence agency, Jeremy Fleming writes: "GCHQ is a citizen-facing intelligence and security enterprise with a globally recognised brand and reputation. We owe all of that to our predecessors."