UK borrowing jumps in September as Covid support continues

- Published

- comments

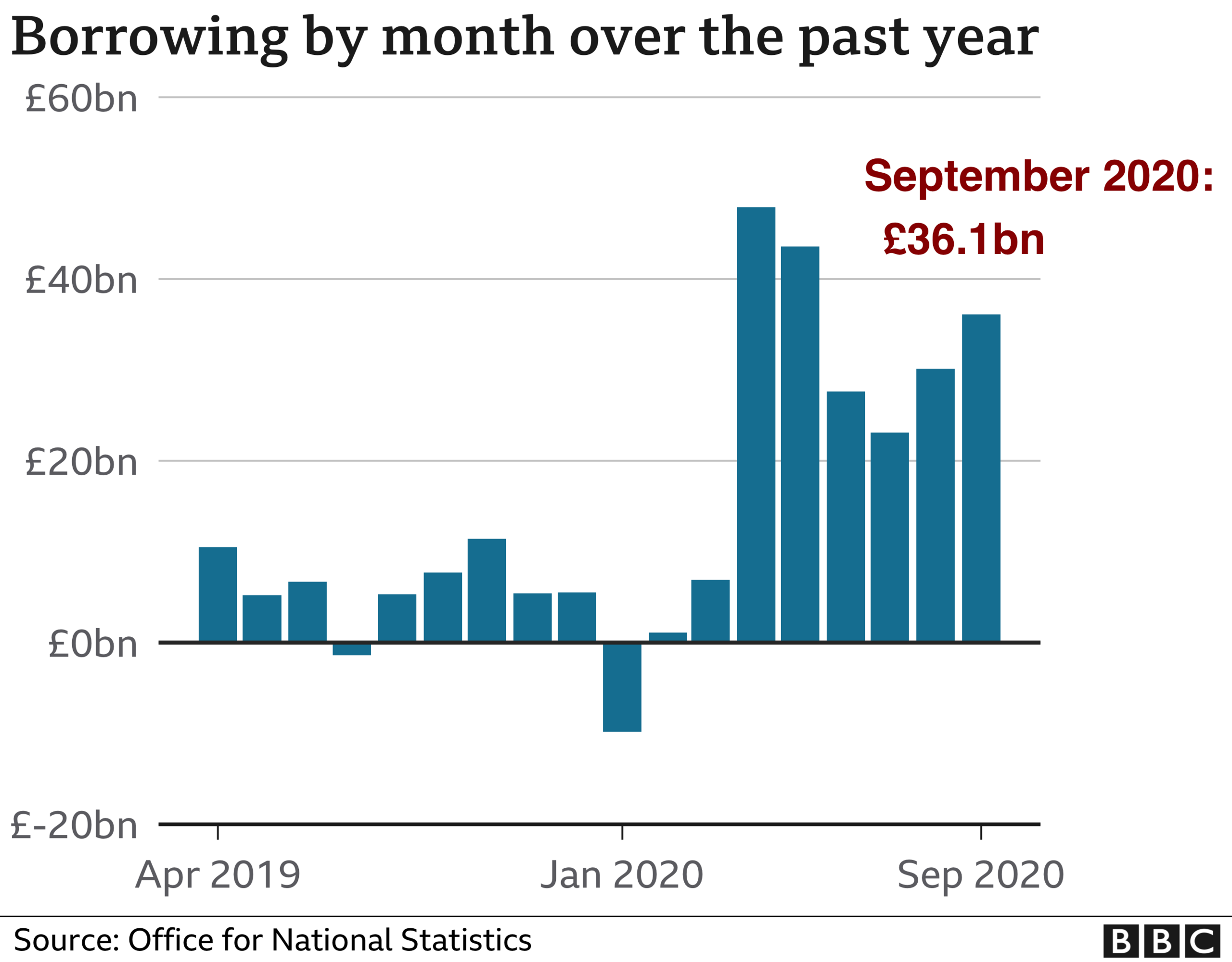

UK government borrowing hit £36.1bn in September as the UK continued its heavy spending to support the economy during the coronavirus pandemic.

At the same time, the Treasury scrapped a three-year spending review.

The figure was £28.4bn more than last year and the third highest in any month since records began in 1993, the Office for National Statistics said.

The ONS said the pandemic had had an impact on public sector borrowing "unprecedented in peacetime".

Extra money was needed to pay furlough wages and support businesses.

At the same time, tax income fell. Lower spending and corporate profits meant the government received less in VAT and corporation tax.

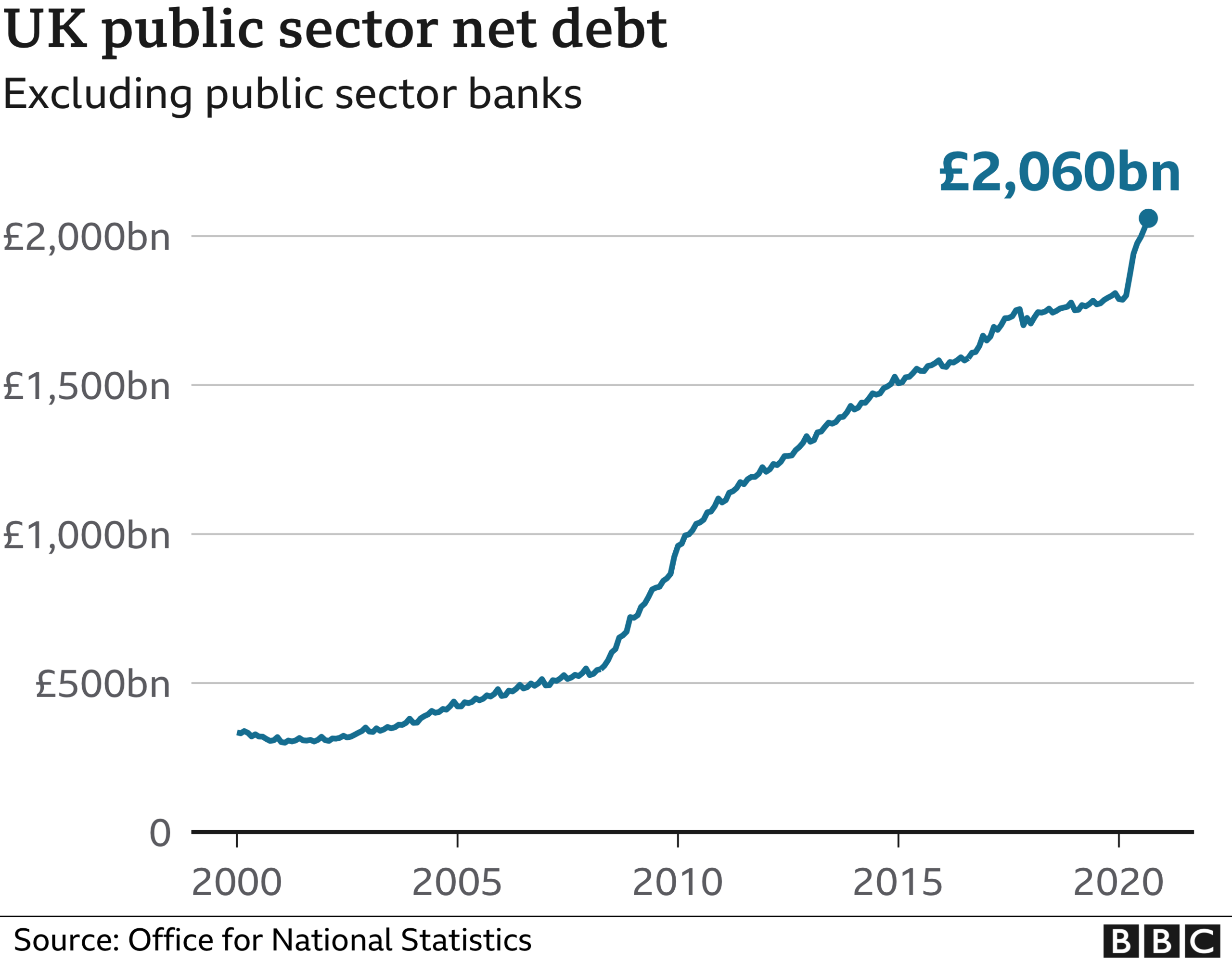

The national debt is now 103.5% of the size of the UK's economy, as measured in gross domestic product (GDP).

The last time debt as a proportion of the economy was so large was 1960. Before that, a peak of almost 250% was reached in the aftermath of World War Two.

Under normal circumstances, such a high ratio may put off lenders to the UK. However, the government can currently borrow money for 10 years at 0.19%.

A debate among economists continues to rage over how much borrowing is too much and whether governments can overspend in a currency they have the power to create.

Inflation figures also out on Wednesday showed that the Consumer Prices Index in September climbed to 0.5%, from 0.2% in August.

Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak said on Wednesday that although the pandemic had had a significant impact on public finances, things would have been far worse with government support.

"I've been clear that our enduring priority is to protect as many jobs and businesses as possible through this pandemic, which is the fiscally responsible thing to do," he said.

"Over time and as the economy recovers, the government will take the necessary steps to ensure the long-term health of the public finances."

Where does the government borrow?

The government borrows in the financial markets, by selling bonds.

A bond is a promise to make payments to whoever holds it on certain dates. There is a large payment on the final date - in effect, the repayment.

The buyers of these bonds, or "gilts", are mainly financial institutions, like pension funds, investment funds, banks and insurance companies. Private savers also buy some.

You can read more here about how countries borrow money.

The impact on government finances was also underlined on Wednesday when the Treasury confirmed it was scrapping a planned multi-year spending review in favour of a one-year review at the end of November.

Economists had warned that the uncertainty of the pandemic and the costs meant setting longer-term spending targets would prove difficult.

Low inflation and low borrowing rates "give the Bank of England and the Chancellor the green light to do more to support the economy," said Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics.

The figures also showed public debt rose further above the £2tn mark, to £2.06tn.

Moody's, a ratings agency, downgraded Britain's sovereign credit rating on Friday to the same level as that of Belgium, saying coronavirus and Brexit threatened the strength of the country's finances.

Economists expect the Bank of England to buy another £100bn of bonds in a bid to keep borrowing costs low, adding to a £300bn shopping list announced in March, a poll by news agency Reuters found.

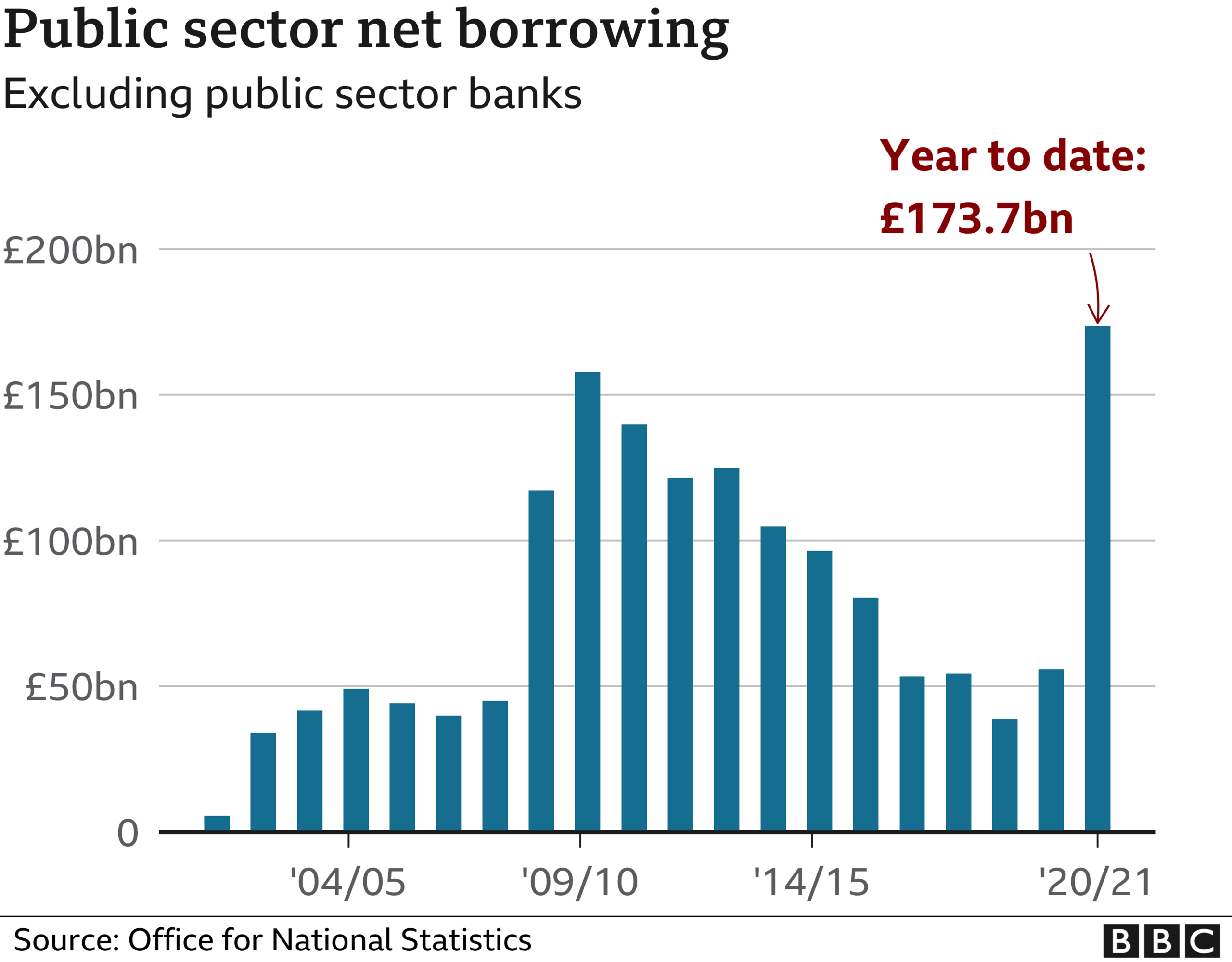

Today's figures put the chancellor's recent claim that "this Conservative government will always balance the books" in context. In the six months from April to September, the public sector borrowed £208bn - the highest amount on record and four times as much as it borrowed in the whole of the preceding financial year.

In the same six months, the government needed £246bn cash - nearly three times the highest cash requirement in any other April-to-September period on record.

That's on track to meet the Office for Budget Responsibility's projection that, over the whole financial year, borrowing could reach £370bn.

If "balance the books" means spending less than your income so you don't have to borrow, then it's a rarity.

In fact, it's happened in just six years of the last 50. The last time wasn't under austerity - but 19 years ago, under Gordon Brown's chancellorship. The chances of that happening in this parliament are vanishingly small.

- Published21 October 2020