Channel migrants: Kurdish-Iranian family died after boat sank

- Published

Four people who died in the Channel when a boat they were travelling in sank were a Kurdish-Iranian family, whose 15-month-old boy remains missing.

Rasoul Iran-Nejad, 35, Shiva Mohammad Panahi, 35, Anita, nine, and Armin, six, were crossing from France to the UK on Tuesday, the BBC has established.

Their baby, Artin, has yet to be found.

Other relatives have been left "confused" and "desperate" as they wait to hear what happened to him, Mr Iran-Nejad's brother told the BBC.

Fifteen other migrants were taken to hospital and an investigation into the sinking has been opened in Dunkirk by the French public prosecutor.

The family were from the city of Sardasht in western Iran, near to the border with Iraq, BBC international affairs correspondent Jiyar Gol said.

The BBC has seen a series of text messages believed to have been sent by Ms Mohammad Panahi on Saturday, including one that acknowledges the danger of crossing the Channel by boat but concludes "we have no choice".

"If we want to go with a lorry we might need more money that we don't have," a second message reads.

Another says: "I have a thousand sorrows in my heart and now that I have left Iran I would like to forget my past."

A friend of the family called 15-month-old Artin a "very happy baby"

Mr Iran-Nejad's brother, Ali, said no-one knows what has happened to Artin.

"Some say he is alive, some say he is dead. We are confused," he told the BBC.

"Our family here are desperate. My father, mother and sisters are crying their eyes out."

He added that the family "paid a lot of money" to get to the UK.

Analysis: The much-travelled route from Iran

by Jiyar Gol, BBC international affairs correspondent

Shiva and Rasoul were two of thousands of Iranian-Kurdish refugees that every year put the lives of their families in the hands of smugglers and go to Europe.

The Kurdish region in Iran has faced both political persecution and economic disparity.

Rasoul's friend, a refugee in Dunkirk, told me in a phone call the family left Iran on 7 August for Turkey, then took a ferry to Italy and then drove to France almost a month ago.

They paid €24,000 (about £21,600) to the smugglers.

Rasoul's brother in the Kurdish city of Sardasht in Western Iran, said his brother sold everything to save his life and seek a better future for his family.

Four bodies lie in a hospital in Dunkirk, but 15-month-old Artin is still missing.

The French coastguard confirmed searches at sea for any further people from the boat did not resume on Wednesday.

Conditions in the English Channel had been rough early on Tuesday and the boat was spotted about 2km (1.2 miles) off the French coast by a passing sailing boat at about 09:30 local time, which alerted French authorities.

Four French vessels, one Belgian helicopter and a French fishing boat took part in the rescue and a search operation. But by the time rescue teams reached the struggling boat, it had already sunk.

French authorities are leading the search and rescue operation

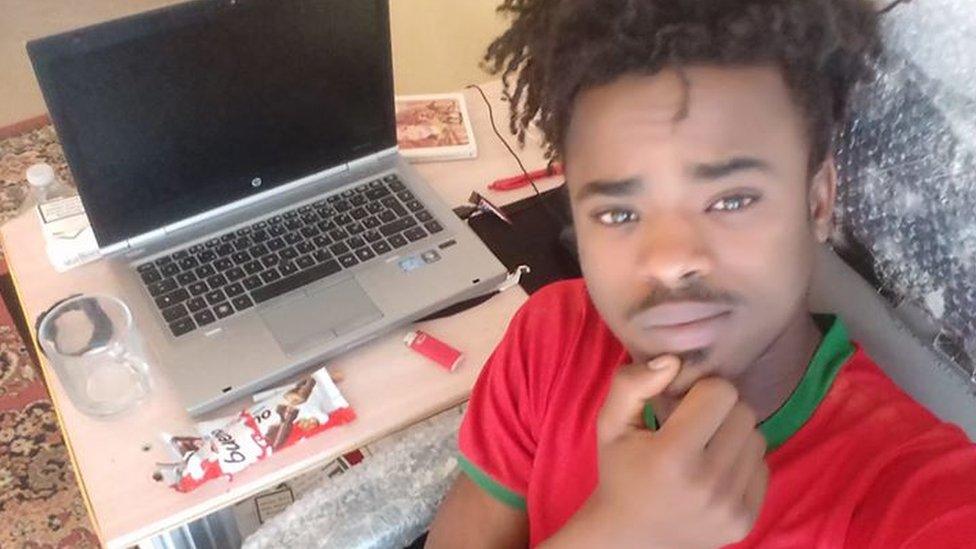

At a camp in Dunkirk, another refugee, Bilal Gaf, said the family had stayed close to his tent for three or four days before they left, and described Artin as "famous" among those staying there.

"He was a very happy baby," he said, showing photographs of himself with the baby, taken around 10 days earlier.

"People are sad, but what can we do? Nothing. Just cry."

He said the family's deaths may deter some people from crossing the Channel. But he said that many, including himself, will "never give up" on getting to the UK - even by dangerous means.

A 20-year-old man living at the same camp, who did not want to be identified, said: "I'm feeling frustrated, angry and heartbroken. My heart is really broken because of this family.

"I used to know the family, I played with the kids."

Asked about why they would risk such a journey, the man - who said he was from the same city in Iran as the family, where Kurdish people have been persecuted - said: "They had to. They really had to. They were frustrated here. They couldn't apply for asylum anywhere else.

"They had family in the UK - I think the father had a brother there."

Bilal Gaf, who spent time with the family, said Artin had been 'famous' in the camp

There are literally hundreds of thousands of refugees in camps or living rough trying to escape to Europe.

The UK is seeing only a tiny fraction of those. Other European countries are seeing and accepting many more asylum seekers.

But why cross a continent and the Channel to come to Britain at all?

There are a number of factors. For colonial and historical reasons, as there are communities in the UK from every corner of the world. Many migrants have family or friends they can connect with.

Another reason is that English is an international language and taught in schools around the world. That makes Britain attractive.

And some are motivated by what the people smugglers tell them. They are known to lie about what life is like in the UK and to create a false sense of urgency, telling refugees to "go now, before the rules change".

The UK does offer protection to around 20,000 refugees a year, but Covid-19 has suspended official routes from camps in Syria and other UN camps.

Charity Care4Calais said the "loss of life should be a wake-up call for those in power in France and the UK".

It said creating a new system that would allow asylum seekers to apply for refuge in the UK from outside its borders would "put an end to terrifying, dangerous sea crossings and stop tragedy striking again".

Save The Children called for a "joint plan" from London and Paris to ensure the safety of vulnerable families, adding: "The English Channel must not become a graveyard for children."

Prime Minister Boris Johnson said his thoughts were with the victims' loved ones.

"We have offered the French authorities every support as they investigate this terrible incident, and will do all we can to crack down on the ruthless criminal gangs who prey on vulnerable people by facilitating these dangerous journeys," he added.

Between 25 and 35 million Kurds inhabit a mountainous region straddling the borders of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran and Armenia.

They form a distinctive community, united through race, culture and language, even though they have no standard dialect. Kurds also adhere to a number of different religions and creeds, although the majority are Sunni Muslims.

They make up the fourth-largest ethnic group in the Middle East, but they have never obtained a permanent nation state.

- Published28 October 2020

- Published21 August 2020

- Published20 December 2019

- Published15 October 2019