Grenfell Tower inquiry: Four possible reasons for the fire

- Published

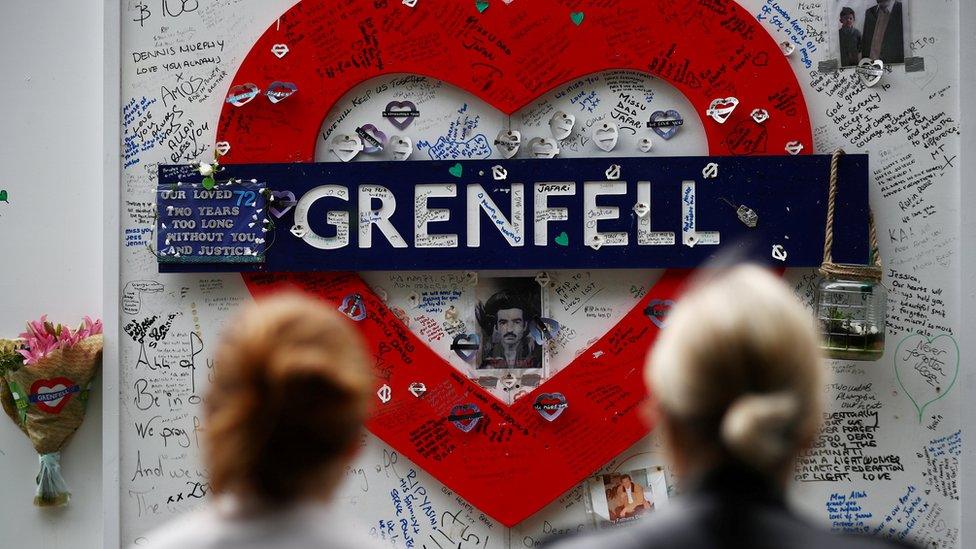

Recently, the Grenfell Tower Inquiry had to be briefly suspended as protesters outside loudly demanded to know why 72 people lost their lives that night in June 2017, and why they hadn't received justice.

The final judgement will be for the inquiry, and possibly the courts.

But at the end of weeks of hearings which have examined the refurbishment of the tower and its role in the disaster, it is now possible to piece together an account, from the evidence presented, of what could have gone wrong.

A lack of expertise

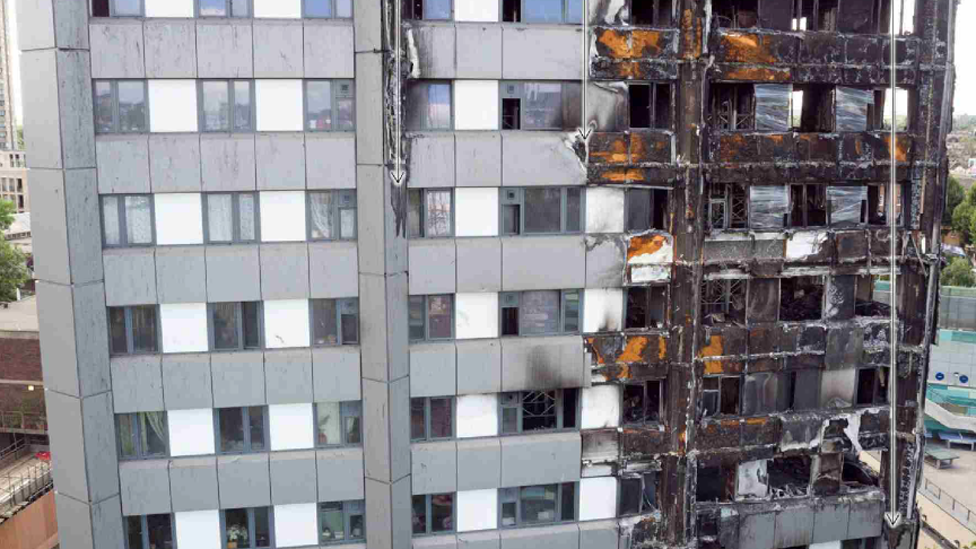

The plan for Grenfell was to add insulation and cladding panels to the outside walls, creating a warmer, drier place to live.

This was a strategy used on buildings all over the UK.

But during these hearings it became very clear those involved with Grenfell didn't appear to quite have a grip on how to do it safely.

This was one of the reasons highly flammable cladding and insulation were used, creating a huge fire risk.

Studio E, the architects, saw cladding a building as "quite straightforward".

Yet the firm's staff had to admit they lacked the experience to tackle a critical question - how to prove their design adhered to the fire safety building regulations.

There was a specialist fire consultant on the job, Exova, an international company.

In 2012, early in the project, Exova visited Grenfell Tower and attended a meeting at which the plans for cladding were discussed.

The consultants produced a series of draft fire safety reports - later disclosed to the inquiry - which failed to mention cladding.

They concluded the proposals would have "no adverse effect" when it came to spreading fire.

But the reports also said the advice was based on what Exova knew at the time.

Since the fire it has insisted it was kept out of the loop and was removed entirely from the project as it progressed.

Rydon, a big construction firm, was signed up to build but also design the new-look tower, despite having no design team.

Its business model involved contracting out the specialist work to companies like the architects Studio E and Exova.

Except that by the time Rydon and its partners decided to change the cladding to a more flammable version, the fire consultants, Exova, were no longer on the job.

What about Harley Facades, which had the contract to supply and fit the panels?

After all, 70% of its refurbishment projects used the same type of panel which went up in flames at Grenfell.

Harley sold itself as a specialist in cladding, but the inquiry heard that was based on experience and during the Grenfell construction it had no-one fully qualified in facade engineering.

A technical manager, Daniel Anketell-Jones, was studying the subject at university and attended a "comprehensive presentation" on cladding fires in October 2014.

He told the inquiry he didn't see it as part of his job, and "might not have been concentrating".

These companies often appeared to assume the council's inspector would do final safety checks.

Unfortunately, the inspector in question, John Hoban, from the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea's Building Control department, had never worked on a high rise cladding project, didn't know anything about the highly-combustible plastic within the panels, and didn't know a fire retardant version could have been used instead.

Large construction projects are always carried out by a complex network of "specialists" and shared responsibilities are completely normal.

But at the start of this phase of the inquiry, victims' lawyers predicted it would be a "merry-go-round of blame".

That is exactly what happened.

Cost was more important than safety

The budget for the work was £9.2m and pressure was on from the start to stick to it.

Rydon had badly wanted the contract.

Its bid was too high, but according to internal emails at the time it had already been tipped off it would win the work, "subject to a small amount of value engineering". Value engineering means finding ways of doing the same job more cheaply.

There was already pressure on Rydon to cut costs. It had accidentally entered a bid which was £212,000 higher than it intended.

Part of the answer was to use cheaper cladding, the now notorious Reynobond PE made from aluminium composite material (ACM).

The council and the tenant management organisation, which managed the tower, were happy with that.

It would save £293,368.

Harley Facades, the cladding firm, preferred the aluminium cladding too. Reynobond was "tried and tested", the company emailed the architects. "We are confident in the cost base."

In fact, Harley said, using it would save more than £400,000.

Rydon kept the difference for itself, without telling the council, according to the evidence of Rydon contracts manager Simon Lawrence.

The focus on cost meant that by the time the work started, a cladding panel which drips molten plastic when exposed to flames had been chosen for a 24-floor building with only one staircase as an escape route in a fire.

No-one realised how dangerous the materials were

The Grenfell Tower inquiry has already concluded that the cladding panels were mostly to blame for spreading the fire.

Many of those involved believed the panels did not pose a fire risk because they had a "class zero" rating, or "class O", as it's universally known in the construction world.

Ray Bailey of Harley Facades said if you take the flame away "it won't continue to burn".

His colleague, Daniel Anketell-Jones, said: "I just understood that class O meant it wouldn't catch fire."

The problem was obvious the morning after the fire.

A class zero panel clearly could burn, and horrifyingly quickly.

Reynobond PE had a plastic middle section, the cheese in a cheese sandwich. And like cheese, it melts rapidly and burns when heated.

The manufacturer of the cladding, Alcoa, now known as Arconic, had commissioned its own, more rigorous European tests. They had not gone well.

As the BBC revealed in 2018, the panels were given worse - and in some cases much worse - classifications than previously made public.

Arconic didn't publish these results in the UK and didn't tell the board responsible for issuing the product certificate relied on by the building industry.

This was despite the company's sales manager, Deborah French, emailing a Grenfell Tower supplier that Arconic, "working closely" with its customers, "was able to follow what type of project is being designed/developed" and then offer the right specification.

Arconic says it was for architects, building firms and cladding companies to ensure their designs were tested and safe.

But it wasn't just the cladding.

Celotex, which made the thick insulation boards used, said their product, when used with cement boards, would be "class zero throughout".

Neil Crawford, associate at the architects Studio E, said in hindsight it was "masquerading horsemeat as beef lasagne".

Why the manufacturers said what they did about their products is the subject of the next module in this inquiry.

Corners were cut

Months of evidence suggested that, during the refurbishment, emails were not followed up, records weren't kept, product specifications were skimmed over, questions raised were not answered, designs were rubber stamped without scrutiny, and the construction work wasn't closely checked.

The companies involved each defended their own work, but also insisted they relied on the other partners in the project to do their jobs properly.

The general level of workmanship at the tower has been strongly criticised.

A key issue was that many of the barriers designed to prevent fire spreading were wrongly fitted.

Seemingly most under pressure was the building inspector, John Hoban.

His department had been cut and was facing competition from commercial inspectors.

He said he was failing to cope with a workload of up to 130 projects.

Despite being regarded as the final pair of eyes checking standards were kept, neither he nor his council department spotted the many fire safety risks at Grenfell Tower.

The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea has admitted its failings and apologised.

Another example stands out.

In November 2014 Claire Williams from the Grenfell Tower management organisation sent an email to the construction company Rydon asking how fire retardant the cladding was.

She described it as her "Lakanal moment", referring to the 2009 fire in which six people died, partly as a result of fire spreading through ACM cladding.

The inquiry has no firm evidence the question was answered, though one witness suggested Rydon's response, at a meeting, was that cladding "would not burn at all".

It was a question central to the safety of the Grenfell Tower project.

If it had been carefully considered, perhaps the coming tragedy might have been prevented.

- Published30 May 2018

- Published29 October 2019

- Published19 October 2020