Grenfell Tower inquiry: 11 key things we’ve learned this year

- Published

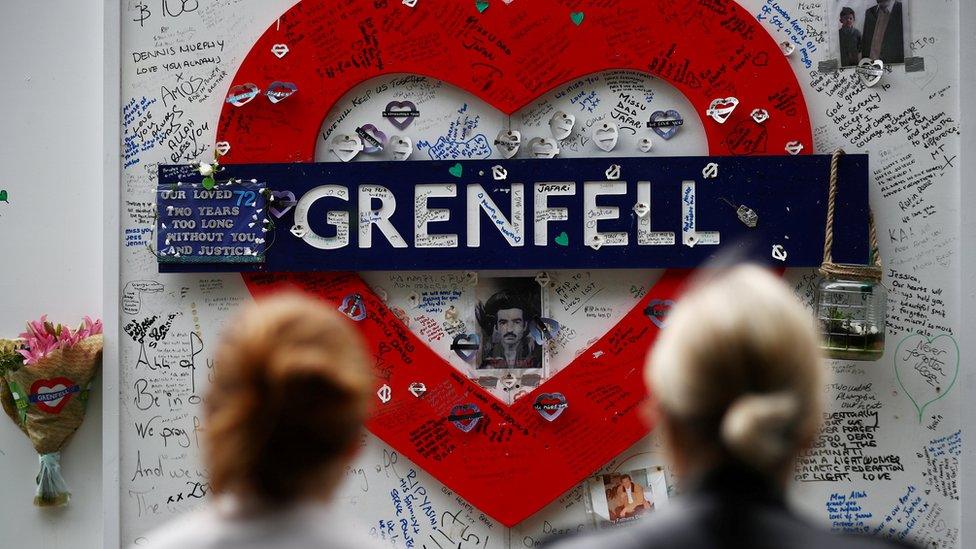

How did Grenfell Tower come to be covered in combustible materials when it was refurbished? That's the question the public inquiry into the west London fire in June 2017 which killed 72 people has been asking.

This year the inquiry has heard more than 400 hours of evidence, from 53 witnesses. The team behind the BBC's Grenfell Tower Inquiry podcast has reported on all of it.

Here's what we've learned.

1. An insulation manufacturer 'lied for commercial gain' when launching its product

Two types of combustible plastic foam insulation were used on the outside of Grenfell Tower.

Staff from Celotex, which made the majority of the insulation, say they behaved unethically, dishonestly and the company lied for commercial gain while getting their product approved for use on high-rise buildings.

Combustible insulation could be used in these situations only if it passed a large-scale fire test.

The inquiry was told Celotex added a non-combustible material to its test, to ensure flames would not reach the company's insulation. It hid the material's use from the fire test report, official certification bodies and even the company's sales staff.

The second company involved was the market leader, Kingspan. For 14 years Kingspan's insulation was sold for use on high-rise buildings without a relevant large-scale fire test.

Its insulation passed a test in 2005 but Kingspan changed the product a year later. Subsequent tests turned into a "raging inferno". Kingspan continued to sell its insulation using the 2005 test on the old material.

This test was only withdrawn in October 2020 after the company accepted it did not represent the product on sale.

When one company questioned Kingspan's approach to sales, technical manager Philip Heath wrote to friends to say they had confused him "with someone who gives a damn".

Philip Heath apologised for the email and said he was "in a dark place" at the time he sent it because one of the friends he was messaging was terminally ill.

2. A stick of dynamite wrapped in foil

Some witnesses didn't have a full grasp of the building regulations. The lead architect had never heard the phrase limited combustibility - the standard recommended for insulation on high-rise buildings.

Others have told the inquiry they thought regulations were ambiguous.

One fire test measured the spread of flame across the surface of a product. Those which performed the best were awarded a classification of Class 0. Kingspan took the surface off their insulation, a piece of foil thinner than a millimetre, and tested that on its own. Then they advertised their whole insulation product as Class 0 - a standard which it did not achieve.

They told the inquiry this was permissible under testing criteria for England and Wales.

3. The merry-go-round of buck passing

Lead counsel to the inquiry Richard Millett has accused witnesses of taking part in a "merry go-round of buck passing". He said the public "would be forced to conclude that everyone involved in the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower did what they were supposed to do and nobody made any serious or causative mistakes".

The inquiry heard how 17 companies worked on the refurbishment through a complex web of contracting and subcontracting.

In evidence, witnesses said they thought other companies were responsible for fire safety.

Specialist cladding contractor Harley sent its drawings to architecture firm Studio E. Harley witnesses told the inquiry they thought the architects were checking that designs met regulations. Studio E said it thought it only had to examine the building's aesthetics and 'functional utility'.

Parts of the drawings which breached regulations slipped through these gaps.

4. Misleading marketing

Construction professionals often relied on meetings with sales staff to decide whether a material was suitable for use.

Celotex's marketing department wrote that those most likely to buy its insulation included anyone who wasn't aware there were restrictions on which materials were permitted for use on high-rise buildings.

The fire broke out in the kitchen of a fourth floor flat in the 23-storey tower block just before 01:00

Celotex and Kingspan staff admitted their marketing material was misleading.

Large-scale fire tests approved entire cladding systems, not individual products. But Kingspan and Celotex marketed their insulation as "suitable for buildings over 18 metres in height".

Jonathan Roper of Celotex admitted this was deliberate and misleading.

Philip Heath of Kingspan said he thought the company's marketing encouraged clients to contact them for more details.

The inquiry heard evidence that on at least one occasion when this happened Kingspan then gave inaccurate evidence.

5. Secret cost-saving meetings

Grenfell Tower was run by Kensington and Chelsea's Tenant Management Organisation (TMO). It hired companies for the Grenfell Tower refurbishment.

The TMO hired architects Studio E who had never clad a high-rise residential building before. (The firm had designed the school and leisure centre opposite Grenfell.)

Under EU rules, expensive public projects were subject to a competitive tender process. When hiring Studio E, TMO staff admitted that they expected the fees would be under £174,000, so they wouldn't have to go through this.

Studio E has admitted that had there been a competitive tender process, it would not have won it.

While appointing a main contractor the TMO breached EU procurement rules by informing one of the companies, Rydon, it was in pole position to win the work before the results were officially announced.

The TMO acknowledges this created a 'risk of challenge' but says it was not illegal.

TMO staff held a "secret" meeting with Rydon to discuss how to cut £800,000 in costs from the budget. This included using cheaper cladding materials. The TMO insists this was subject to the agreement of planners.

6. Combustible insulation was energy efficient

One of the aims of the refurbishment was to improve the energy efficiency of the tower.

A company called Max Fordham gave Grenfell an "aspirational" target of making the 1970s concrete block as efficient as a new build project.

Max Fordham suggested two insulation materials that could achieve this. But they did not check the building regulation guidance to see if the products could be used.

The architects, Studio E, also made no checks to see whether the combustible materials were compliant with building regulations. It described any concerns its staff may have had about the compliance of the insulation as an "afterthought".

7. Asking questions

Many witnesses are asked whether, if they had their time again, they would do anything differently. Terry Ashton, who worked for the fire safety consultants Exova, was clear - he would have asked more questions.

Exova completed three fire safety strategies for the Grenfell Tower refurbishment. None of them even acknowledged the crucial fact that the refurbishment involved cladding the outside of the building.

Seventy-two people died as a result of the fire

Mr Ashton said he would have expected the architects to have directly asked him to consider the safety of the cladding products. They did not, so he didn't.

Other Exova staff failed to clarify missing information. Exova's fire safety strategy for the existing building used the word "assumed" 19 times in a 16-page report.

8. Poor workmanship

After the fire, when investigators looked at the cladding that had been installed on Grenfell Tower, they found a catalogue of errors related to how it had been installed.

Many cavity barriers - intended to stop fire spreading through cladding - were poorly fitted or installed in the wrong place. Some were attached back to front, stopping them working.

The company responsible for installing the cladding, Osborne Berry, admitted there were examples of unacceptable poor workmanship which should have been ripped out and redone.

Grenfell Tower had new windows fitted. During the installation Rydon instructed its subcontractors, SD Plastering, to fill gaps around the windows with combustible insulation. They said neither knew it was combustible.

On the night of the fire, this was the main route for the flames to spread into the cladding.

9. Checks and balances

Kensington and Chelsea's building control department approved the construction of the Grenfell refurbishment.

John Hoban did not notice that cavity barriers had not been designed around the windows to stop flames spreading to the outside wall. He failed to recognise the cladding materials were not suitable for use together on high-rise buildings.

Mr Hoban told the inquiry that as a result of local authority cuts, he was juggling up to 130 projects.

A clerk of works was hired to inspect the work carried out on the cladding. His company charged more than £400 a day, but he said his remit was not to check whether the work met regulations, or matched architects' drawings. Jonathan White said he only checked that work was neat and tidy.

10. Rebel residents

The TMO consulted residents about plans for the building. TMO newsletters claimed there was "no concern from residents about cladding the building". But that was based on a meeting which just one resident attended. Information about fire retardancy was not given to residents.

During the refurbishment, people complained about the standard of work. The project lead for the main contractor Rydon said the company and other contractors were under massive pressure from "rebel residents". During evidence he repeatedly called the residents of Grenfell Tower "vocal" and "aggressive".

Complaints were also made about construction staff who knocked on windows asking for cups of tea, scared pets and dropped materials onto a public footpath.

11. A taste of what's to come

In January the inquiry expects to hear evidence from Arconic, which made the cladding panels. The inquiry has already found the product, with a combustible polyethylene core, was the main cause of the spread of the fire.

Campaigners delivered a message to the French embassy in London urging witnesses for cladding firm Arconic residing in France to give evidence

A lawyer who represents some of the bereaved, survivors and residents has described Arconic (along with the insulation manufacturers Celotex and Kingspan) as "little more than crooks and killers" who "knew their material would burn with lethal speed".

The inquiry has heard that in 2009, a senior Arconic employee called polyethylene cores "dangerous". In 2015, while cladding was being installed on Grenfell he wrote: "We really need to stop proposing PE [polyethylene] …. We are in the 'know'."

It's unclear whether all the Arconic witnesses will give evidence. Some are arguing that a French law prevents them from disclosing commercial information in foreign judicial proceedings.

Lead counsel to the inquiry Richard Millett has urged them to "do the right thing".

Kate Lamble is the presenter and producer of the BBC's Grenfell Tower Inquiry Podcast. She has followed every day of evidence since the start of the hearings in June 2018.