The celebrity hairdresser with a secret of his own

- Published

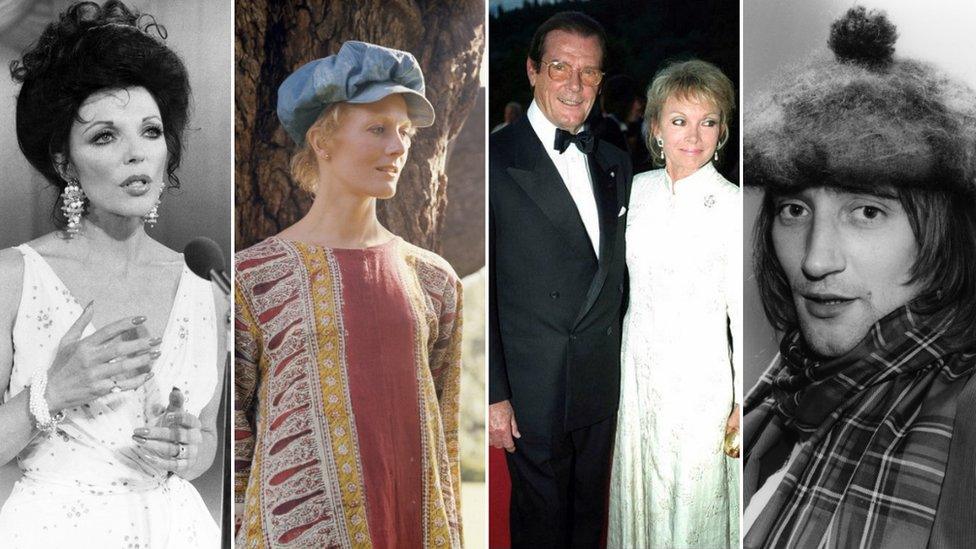

John Harding's customers have included Joan Collins, Vanessa Redgrave, Roger Moore and Kristina Tholstrup, and Rod Stewart

For 35 years, the rich and famous came to John Harding's central London salon to get their hair cut, coloured, and styled. Joan Collins; Vanessa Redgrave; Rod Stewart; Tony Curtis; Kristina Tholstrup and occasionally husband Roger Moore; Sarah Churchill; and many more.

The salon was on Elizabeth Street, Belgravia; a place where leafy garden squares reflect in the polished brass plates of embassies and hedge funds.

"There were lots of wealthy people in the area," says John, now 77. "Lady this and Lady that."

But the actors, singers, and aristocrats who came to John's salon would not have guessed his secret. Unless, that is, they noticed that he rarely answered the phone. That's because, if he did answer, he might need to check the appointments book, or write something down.

And that was a problem - because John Harding, hairdresser to the stars, was unable to read.

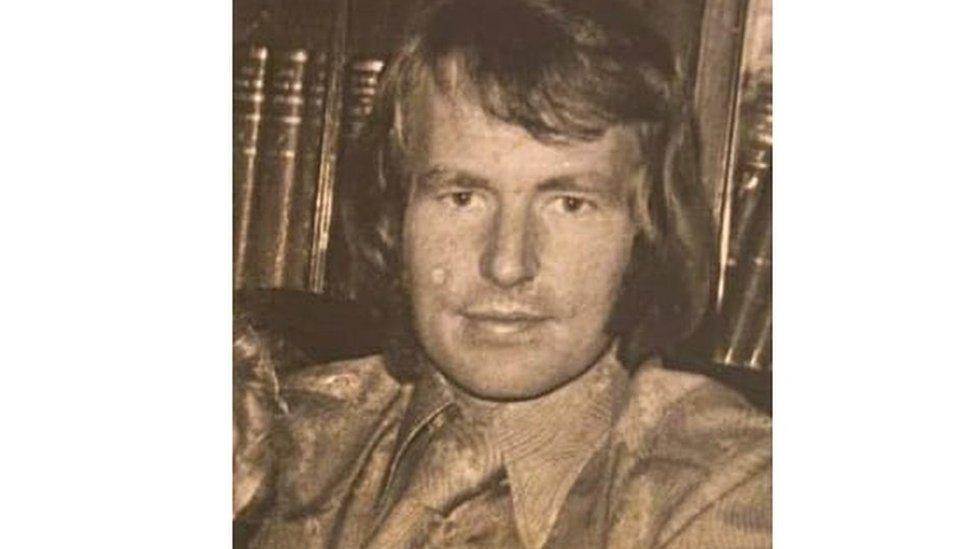

John Harding and wife Heather, pictured about 30 years ago

John grew up in Islington, north London, and went to Laycock School. He wasn't uninterested - "I liked art, geography, history, and my maths was OK" - but always found reading "very difficult".

He soon found himself in D class, the bottom rung, and stayed there. He doesn't blame his teachers -"If there's 30 in a class, it's hard to help out" - or his parents.

"My mum wasn't a very good reader, and my dad wasn't either," says John. "My dad was a working class man - he was in the printing trade, a union man - and he didn't have a lot of vocabulary. He didn't have time to help me, but that was a man of that era."

John could recognise three-letter words from memory, but "just didn't have any idea how to break longer words down".

"I couldn't read something that was interesting like a history book or a geography book," he says. "That was too far."

He doesn't think he had dyslexia, but he was never tested. So he stayed in D class, hiding it from friends, bluffing as best he could, until it was time to leave. How did those school days feel?

"It's more of an embarrassment, you know?" he says. "I used to get very edgy when it came up."

At 16, it was finally time to leave school. But what jobs were there for boys who couldn't read? He was good with his hands, but didn't want to be a carpenter, electrician, or plumber. "You had to get up too early," he jokes.

And so he took a job at the hairdressers round the corner - sweeping the floor, washing the hair, and avoiding the appointments book.

John Harding in 1970, aged 28, after opening his first salon

After Islington, John progressed to salons in Kennington, Pimlico, then Mayfair. But it was difficult to learn the trade - after all, who wants their hair cut by a beginner? So, in his own time, he went to academies in the evenings. He "won a few competitions" and, when John was 20, an ex-colleague asked him to join his new salon in Pimlico.

"He offered me good money," says John. "I told him I'd do it - provided I didn't have to do any bookwork."

It proved a life-changing decision. At Pimlico, the receptionist introduced John to her sister, Heather, and they were soon married. She became one of the few people to know about John's illiteracy.

"She was very clever. She did all that stuff for me."

Looking back, says John, he should have learned to read then. But with a new wife, and soon a young family, he "put it on the back burner". It didn't affect his career - aged 25, he opened the successful salon on Elizabeth Street where he would stay for 35 years. But outside the salon, the challenges remained.

"If we went to a restaurant with friends, my wife would say 'You'd fancy this John', knowing full well I couldn't read it on the menu," he says. "Basically, you bluff your way through life. It's crazy the things you make up."

So did any of his customers - Collins, Redgrave, Churchill, et al - know he couldn't read? "None at all," he says.

John Harding with daughter Fiona last Christmas

In his 50s and 60s, John twice tried to learn at evening classes. "But I felt I wasn't really getting very far," he says.

"It was difficult for the teachers to have time with you. The teacher would let you read alone, then give you 15 minutes of her time. Which is good, but not as good as one to one."

So John may have stayed illiterate. But then, eight years ago, he came home to find Heather - his wife of almost 50 years - dead in their lounge. She had suffered heart failure aged 69.

Illiteracy in the UK

One in six adults in England - about 7 million people - has "very poor literacy skills", according to OECD statistics quoted by the National Literacy Trust., external The figure is one in four in Scotland, one in five in Northern Ireland, and one in eight in Wales.

Read Easy, external - the group that helped John - says 2.5 million adults in England can "barely read at all". "This has a massive impact on people's chances in life and affects them in so many ways," says Ginny Williams-Ellis, Read Easy's founder and chief executive.

Without Heather to help him "bluff", John decided to try again. His children Gerard, now 53, and Fiona, 51, supported him, but he wanted to fix the problem that had plagued him since those long days at Laycock School. Three years ago he saw an advert for Read Easy, external, a non-profit group that uses volunteers to help teach adults in one-to-one sessions.

"I got in touch," says John. "And I haven't looked back."

Because of Covid, the weekly one-on-one sessions with his coach, Yvonne Nicholas, now take place online, rather than in person - but the progress continues. John now reads the newspaper - "the Daily Mail or the Daily Mirror; the Sunday Times might be a bit beyond me" - and plans to read his first book. More importantly, he is "much more confident" in day-to-day life.

It's a change his coach has noticed, too. "Although he is naturally modest, I know he is proud of himself," says Yvonne. "He really is a far more confident person now."

John still works at his daughter's salon in St Katherine's Dock in London - a business that carries his name, external. It might only be a few miles from Islington, but he has come a long way from sweeping the floor, aged 16, at his neighbourhood hairdresser.

Before the interview ends, John mentions that another reading charity, Coram Beanstalk, has seen an 80% drop in the number of volunteers going into schools to help children read. Most of the volunteers are older, John explains, and they're having to shield or self-isolate.

So how did John find out about this?

"I read it in the Evening Standard, external last night," he says, as if it's the most normal thing in the world.

Other inspiring stories