A-level and GCSE results: What do students and teachers think?

- Published

GCSE and A-level students in England will now receive grades from their teachers, after exams were cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Schools will decide the grades students get this summer using a combination of mock exams, coursework and essays.

The BBC has spoken to students and teachers to find out how they feel about the new system.

'The fairest way to grade us'

Caitlin Orsborn, an A-level student from Rotherham, South Yorkshire, admits she and her friends are "relieved" that teachers will decide their grades.

The 18-year-old says: "We're all relieved this morning because we have been working towards nothing for two months."

She believes teacher-awarded results are the "best way" for students to be graded this year, explaining that "being in and out of school so sporadically has really affected so many students' level of work and mental health".

"So to make exams compulsory, in my eyes, was never a good idea," she adds.

Caitlin says it has been "unbelievably stressful", especially for GCSE and A-level students having to continue their studies without knowing what is happening.

She adds that although there are "flaws" in the new system, it is the "fairest way" of grading students.

'The best choice of a bad bunch'

Max Peel, an A-level student from London, says it was "great" to get clarification from exams watchdog Ofqual on the situation because everything had "felt so uncertain up to this point".

The exam board has said there will be optional tests or "mini exams" for all subjects, but they will not be held in exam conditions or decide final grades.

Speaking to the BBC, Max, 18, says there is general "consensus" among his school friends that "given the amount of time that's been lost in in-person education", not having to sit formal exams was the "best choice of a bunch [of] bad options" the government has.

However, he admits he's concerned about the "potential risk of grade inflation" and how his results will be compared to those of other students across the country.

Max says: "All that we can hope for is individual moderation and for appeals to take place", adding the fact that results will be published earlier in August will "give more time" for these appeals.

"It's not going to be perfect, and I'm sure there are going to be problems that crop up but I think everyone's trying to make the best of it," he adds.

Max also feels sorry for teachers, who he says will now face "yet more work and pressure" to devise a system to award grades for what could be hundreds of pupils.

He says the government is "pushing the responsibility" for grades onto schools and teachers to avoid a repeat of last summer, when thousands of A-level students had their results downgraded from school estimates by a controversial algorithm.

The exam board later announced a U-turn which allowed them to use teachers' predictions instead.

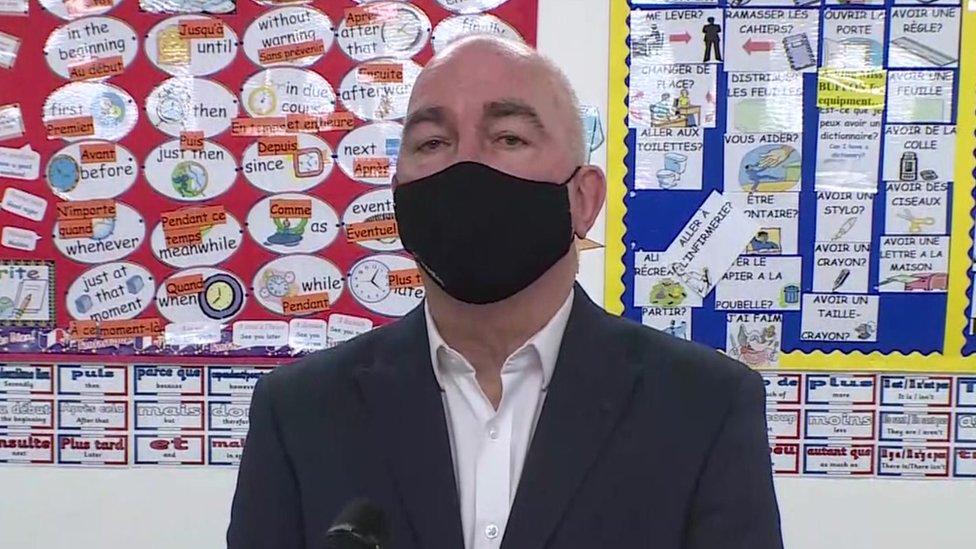

'The devil is in the detail'

Ges Smith, head teacher at Jo Richardson community school in Dagenham, east London, said while he was "happy" with the new system "as a process", there were still "issues" to be "ironed out".

Speaking to the BBC, he says the "devil is in the detail" and his "major concern" is over results being published earlier this year.

Ministers have said the move is to give students more time to appeal if they're unhappy with their grades.

But Mr Smith warns it will cause "significant problems" as some of his staff were hoping to take holidays as lockdown restrictions ease.

He says: "At the very stage that we're going to be starting an appeals process, the people who are going to need to be around, who have done the assessment, who have the work [and] access to the data, are potentially not going to be available."

The head teacher argues that it will be "really difficult to get consistency" across the country, as schools will be using "different methods of assessment" to grade pupils.

"You will have a number of different units taught at different schools, you will therefore be assessing different units.

"Some schools will use the tests that are going to be offered, some schools will use their own mock results, some will use their own teacher results, so it's going to be really difficult to get that consistency across the country."

He says there will be a process in place at his school for grading students, which will involve "rigour... standardisation and moderation" with the exam board taking samples, but staff still needed to find out "how that process is going to be effective".

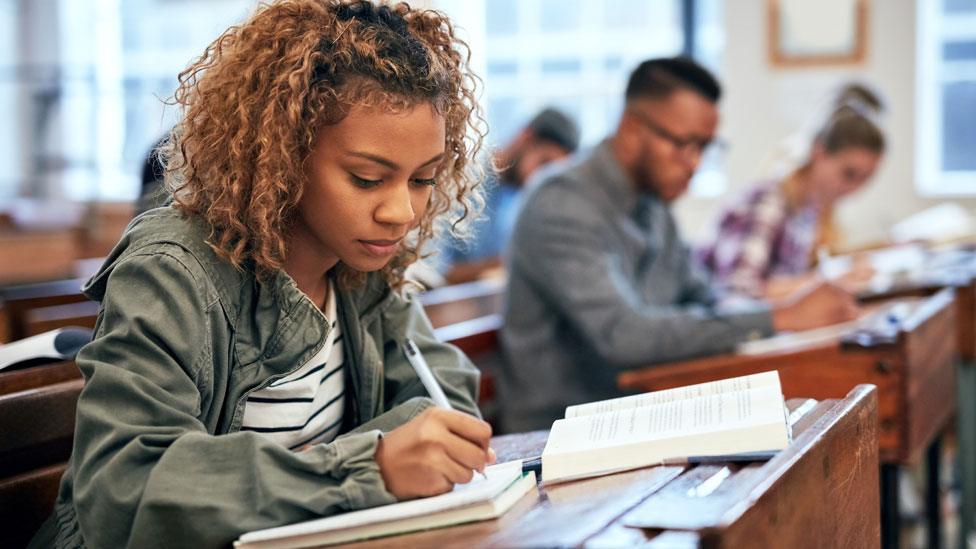

'Will my grade count for as much?'

Abigail, an A-level student at the school, said she has been "worried" about how her grade will be viewed in comparison with previous years.

Asked if she thought her grades would count as much as in other years, she tells the BBC: "That has been something that I've worried about - that when people see I was the year that was in Covid, it might not look the same as somebody who sat a real exam.

"That has definitely been a worry."

'Nothing to work towards'

Meanwhile, Samuel, an A-level student at the same school, says it's been "quite difficult" to feel motivated to study "without an end goal".

He says: "Without an exam, you don't really know what you're working for in the morning and you don't really have anything to work towards.

"You work in the same environment to revise, to study, and for leisure - it's quite difficult for your work-life balance."

Samuel says he "wouldn't mind" sitting an exam but that he understands that it is "quite difficult" for the exam board to set and moderate a standardised test when students across the country are at "different stages".

- Published25 February 2021

- Published23 February 2022

- Published24 February 2021